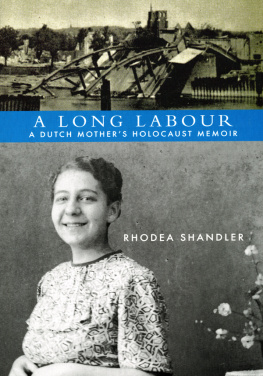

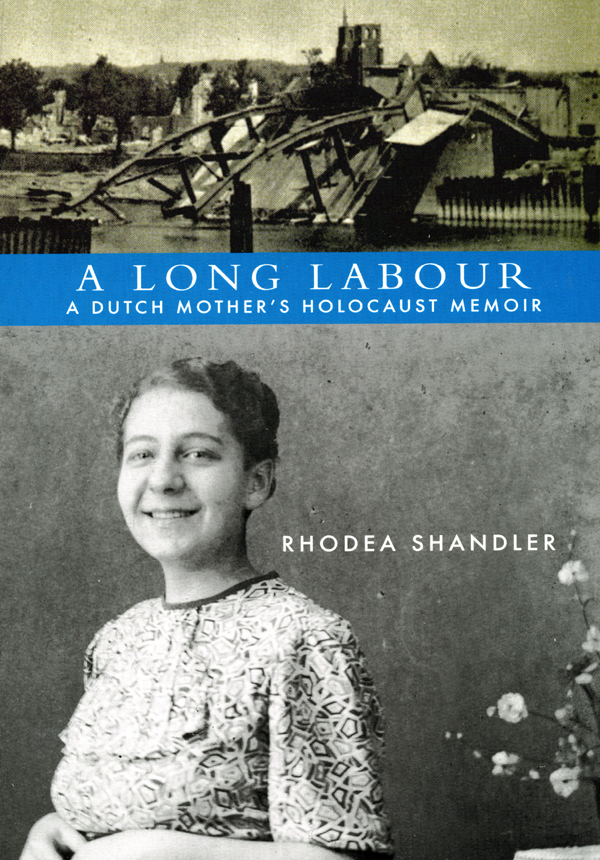

A LONG LABOUR

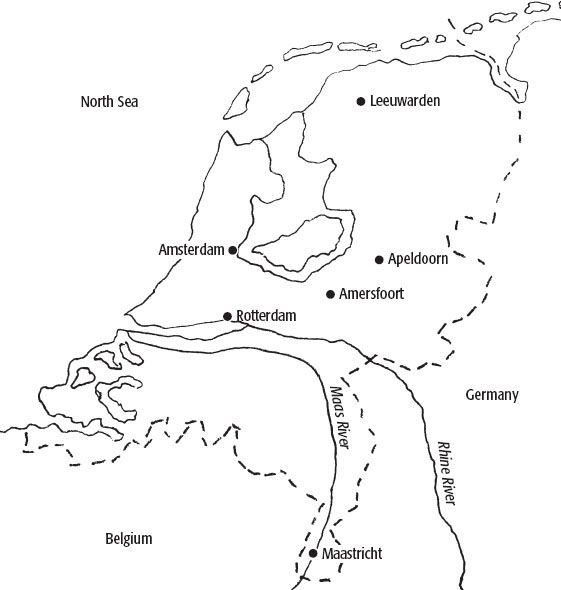

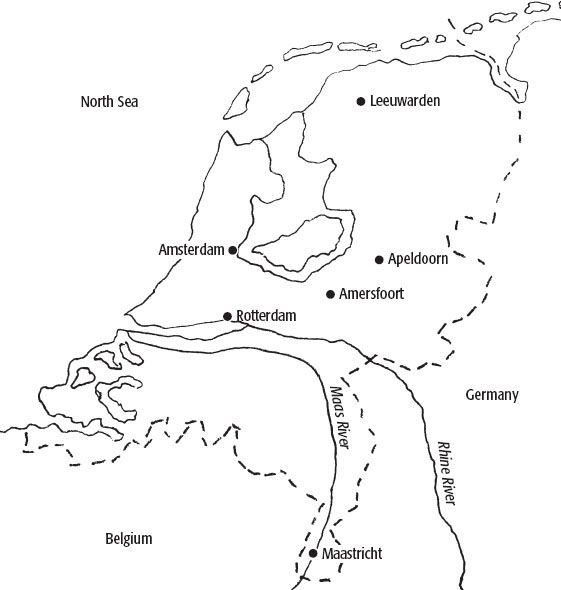

The Netherlands

A LONG LABOUR

A DUTCH MOTHERS HOLOCAUST MEMOIR

RHODEA SHANDLER

INTRODUCTION BY

S. Lillian Kremer

AFTERWORD BY

Roxsane Tanner

RONSDALE PRESS &

VANCOUVER HOLOCAUST EDUCATION CENTRE

A LONG LABOUR

Copyright 2007 Rhodea Shandler

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher, or, in Canada, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency).

RONSDALE PRESS

3350 West 21st Avenue

Vancouver, B.C., Canada V6S 1G7

www.ronsdalepress.com

Typesetting: Julie Cochrane, in New Baskerville 11 pt on 15

Cover Design: Denys Yuen

Cover Photo: Rhodea as a young woman; Arnhems destroyed bridge

Back Cover Photo: Rhodeas two children born during the war Elly and Johanna

Paper: Ancient Forest Friendly Silva 100% post-consumer waste, totally chlorine-free and acid-free

Ronsdale Press wishes to thank the following for their support of its publishing program: the Canada Council for the Arts, the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, the British Columbia Arts Council, and the Province of British Columbia through the British Columbia Book Publishing Tax Credit Program.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Shandler, Rhodea, 19182006.

A long labour: a Dutch mothers Holocaust memoir / Rhodea Shandler; introduction by S. Lillian Kremer; afterword by Roxsane Tanner.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-55380-045-3 (print)

ISBN 978-1-55380-276-1 (ebook) / ISBN 978-1-55380-275-4 (pdf)

1. Shandler, Rhodea, 19182006. 2. Holocaust, Jewish (19391945) Personal narratives. 3. Jews Netherlands Biography. 4. Dutch Canadians Biography. I. Title.

DJ283.S43A3 2007 940.5318092 C2007-901793-2

At Ronsdale Press we are committed to protecting the environment. To this end we are working with Markets Initiative (www.oldgrowthfree.com) and printers to phase out our use of paper produced from ancient forests. This book is one step towards that goal.

Printed in Canada by Marquis Book Printing, Montreal

To my parents,

brother, family and all

Holocaust victims

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank my daughter Judy Shandler for her help with the manuscript. When I began writing this memoir she was invaluable in reading and editing what I wrote. She helped also in asking me questions so as to enable me to go back into my past and bring it to life again. I would also like to thank the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre for arranging for Bettina Stumm to come to my home with her tape recorder to ask further questions so as to fill in the missing parts of the memoir. Bettina faithfully transcribed my accounts and became a friend to me in the process. When she encountered any confusion between my accounts, she would carefully clarify the material so that the memoir would be as accurate as possible. Without my daughter Judy and Bettina, this memoir would never have been brought to a conclusion. I cannot thank them enough. Needless to say, however, I take full responsibility for any errors of fact or omission in the memoir. I have tried my best to speak truthfully of what I know and experienced.

Special recognition is extended to Morris Wosk, zl, businessman, community leader and philanthropist and to his son Rabbi Yosef Wosk, who, though a major gift to the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre in 2000, established the Wosk Publishing Program. In recognition of the Wosk familys deep interest in Jewish history, the mandate of the Wosk Publishing Program is to publish original writings that advance our understanding of the events of the Holocaust, its history, implications and effects.

Thanks are also extended to Dr. Lillian Kremer for her Introduction and to Roxsane Tanner, who, speaking for her brother and sisters, contributed the Afterword.

Introduction

S. LILLIAN KREMER

Rhodea Shandlers A Long Labour: A Dutch Mothers Holocaust Memoir is best understood within the context of the larger Dutch Jewish Holocaust experience and womens Holocaust narrative. The Dutch suffered enormous hardship during five years of occupation by Nazi Germany. Beginning in 1940, Dutch Jews were systematically identified and isolated. From 1942 to 1944 virtually all the nations Jews who neither fled Holland nor were in hiding were deported to Bergen-Belsen, Theresienstadt, and the killing camps, primarily to Auschwitz-Birkenau and Sobibor from Westerbork and Vught Dutch transit camps. The fortunate few in hiding who avoided death among the ranks of underground resistance fighters or during the Dutch-wide hungerwinter of 19441945 experienced constant fear of detection and denunciation, physical deprivation and psychological anxiety throughout the occupation. Whereas two of every three European Jews were murdered in the Shoah, three of every four Dutch Jews perished. Dutch civil servants cooperated in the disenfranchisement of Jewish citizens, stamping Js on their identity documents, confiscating their bicycles and radios, and sending unemployed Jews to labour camps. Dutch police actively participated in the deportations, and collaborators routinely facilitated Nazi objectives.

Following liberation, the surviving Jewish remnant found that their gentile compatriots were, in the main, disinterested in their experience and focused instead on their own hardships under Nazi occupation. In the late 1960s, Holland encountered the generation gap that affected other European nations. The older generation was de-mythologized, students criticized the establishment, unmasked the resistance myth, exposed the lie of a widespread heroic response to Nazism by their parents, and began to pay more attention to the Dutch Holocaust experience. With publications such as Jack Pressers Ondergang (Ashes in the Wind) mapping the abandonment and betrayal of Dutch Jewry despite its integration in Dutch society, the nation began to confront the past more objectively. Historians Dick van Galen Last and Rolf Wolfswinkel (Anne Frank and After: Dutch Holocaust Literature in Historical Perspective), who chart the changing tides of interest from focus on the collective history to focus on individual stories, observe that since the 1970s, World War II literature and film have been welcomed in Holland, with resistance and collaboration the most popular subjects in general literature and the Holocaust a major theme for Jewish writers.

Dutch Holocaust literature documents conditions of Jews in hiding and incarcerated in the transit camps awaiting deportation to the killing centers, records the paradoxical role of the Jewish Council, and the survival struggle within the concentration camp universe. Among the victims writing of their ordeals while they were occurring are Anne Frank, who recorded her experience of being in hiding with her family, and Etty Hillesum and Philip Mechanicus, who described the horrendous physical conditions and camp administration of Westerbork and the psychological terror of inmates awaiting deportation. Other writers offered testimony at wars end. Upon his return from Bergen-Belsen, Abel Herzberg analyzed the behaviour of inmates and their reaction to the harsh camp conditions. Many years following liberation, Gerhard Durlacher recorded his experiences in occupied Holland, Theresienstadt and Auschwitz. Marga Minco addressed her wartime experience through the perspective of a fifteen-year-old narrator charting the incremental development of isolation and oppression in a narrative style blending directness and constraint.