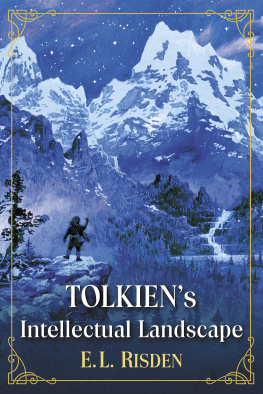

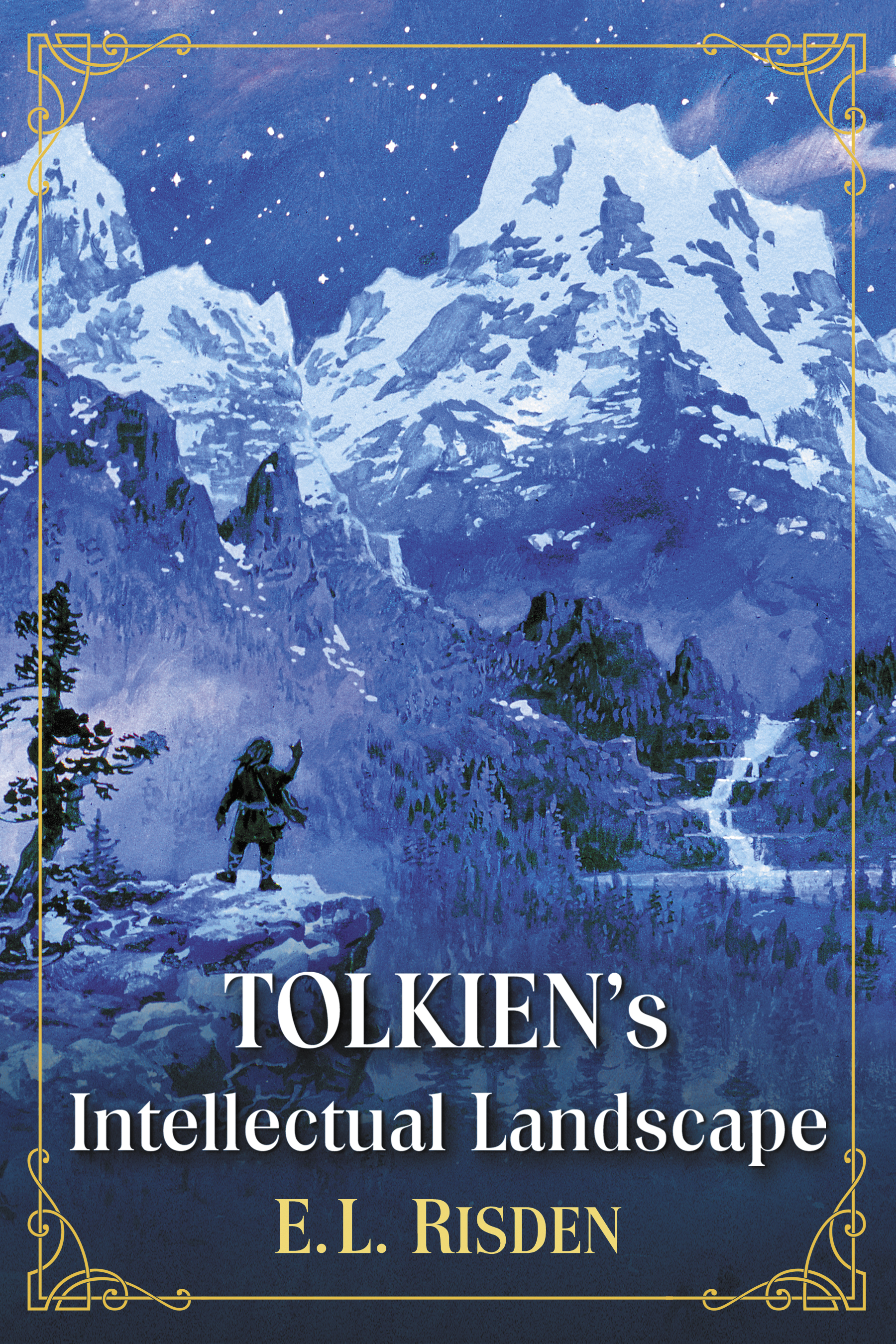

Tolkiens Intellectual Landscape

E.L. Risden

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-1998-9

2015 E.L. Risden. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Cover art: Ted Nasmith, detail from Durin I Discovers the Three Peaks, gouache on illustration board, 2011

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To Tom Shippey and Verlyn Flieger

for heroic scholarship and friendly encouragement

Introduction:

The Author of the Century in His Century: Extending the Intellectual Landscape

The growing body of scholarship on the life and works of J. R. R. Tolkien up to about the year 2000 had not necessarily placed him fully in the midst of the rapidly changing and vastly diversifying intellectual life of the twentieth century. Since then, Peter Jacksons films created, as Tom Shippey has called them, collectively, another road to Middle-earth, and so they have in another way modernized him and initiated another road to Tolkien scholarship as well. Shippeys sometimes controversial book (especially for those who didnt read it) J. R. R. Tolkien: Author of the Centuryalong with the movieshelped bring Tolkien from popularity among his readership and fandom to a focal point of social and cultural debates (again largely among those who didnt read Tolkien). How, Shippeys book asks, could a professor of medieval language and literature and author of fantasy fiction have continued to rise in popularity and admiration among both general readers and scholars in a century with an increasingly complicated and diverse intellectual landscape? Those willing to read Tolkiens work have long known the pleasure of his fictional world, but how could readers term a fantasy author author of the century? Shippey answered those questions profoundlyagain, if critics bothered to read his book rather than simply to respond to its title. Yet we may say more about both author and century together: why has Tolkien remained for his readers so central to a time when so many readers have embraced him and some few critics have disparaged him? For one reason, while those who havent read him often steadfastly keep their distance, those who do read him usually re-read him, periodically, and they want to talk about him, read what others say about him, and write about him themselves. We do so partly, I think, out of love for his fictional world, a place that we want to be real despite its origins in imagination, and partly because we find there and in Tolkiens nonfiction writing as well a landscape of ideas that we wish to consider furtherand that stick with us whether we will or no. Tolkiens ideas connect as creeks do to rivers and rivers to seas, valleys to hills and hills to mountains: they map out the experience of a man and a century; they search for value amidst torrents of trouble dotted with occasional rays of hope.

The appeal of Tolkiens thought and world comes from many sources, one of which may seem odd to many readers in our time, though not those who have considered Tolkien as philologist: Tolkien the fiction writer succeeded because of Tolkien the scholar. He knew how to move from one frame of thought to another, to use what he learned about language and story to create a complex world full of language and story. Though he preferred fiction to criticism, his criticism tells us a good bit about how his ideas fueled his composition. In many ways he was an ordinary mana family man, a Catholic, a lover of his country, someone who appreciated deep friendship, good talk, and good beerwith extraordinary gifts of language and imagination. He drew inspiration and got encouragement from his fellow Inklings, but didnt feel bound by their separate courses, nor did he get from them many ideasthough he did get significant response as he shared with them a great deal of his work. His language study (from childhood on) and his sense that language held within it innumerable stories, his knowledge of many old and wonderful tales, his spiritual devotion and deep, abiding interest in moral problems (e.g., the genesis and practice of evil, and of good), his first-hand knowledge of war and yet his love of simple English country life obviously influenced his fiction. So did a childhood of loss and separation followed by an adulthood of family and male friendship; all contributed to the concentration of ideas that inhabit his work and that still find appeal for readers, even if all his ideas dont sit at the cutting edge of contemporary literary theory (though his practice sometimes does).

In Tolkien scholarship, what others have written about him, we have seen particular concentration on Tolkien as philologist, as Catholic, as war survivor, as beloved creator of the epic-fantasy trilogy and besieged author of escapist fiction for boys; scholars have seen those points (those right and wrong) as both positives and negatives, depending on their own preferences. While I think Tolkiens appeal comes mostly from the pleasures of the world he created, the realization of interesting beings with fascinating and terrifying problems to solve, I believe it comes also from his willingness to express the ideas that unfold in that world clearly and powerfully, whether he might have expected a broad audience to agree with his views on them or not. Those ideas come from his life and from the development of his world, and whether those persons in positions of intellectual power wanted (or want) to deal with them or not, they stand at the center of the great issues and great events of the twentieth century. My study here aims to expand on the context and ideas of Tolkiens work, to stretch the critical compass for additional examination of the landscape of his thought, and to extend the argument that Tolkiens writing fits rather better than one may guess amidst the intellectual movements of his lifetime. What we believe, how we understand meaning, how we live in a world afflicted with human-wrought horrors, how we deal with one another, how we forgive or at least go on, how we deal with death and our impulses toward destructiveness and self-obsession: everyone in the twentieth century who thought about anything thought about those issues. Tolkiens work, we shouldnt be surprised, creates a considerable, complex, and significant matrix of ideas that fill out the landscape of Middle-earthand also that of academic and popular thoughtwith far more than a collection of mere fantasy stories. They touch heaven and earth and much of normal, daily life and of extreme circumstances in between.

Recent scholarly work has expanded into how Tolkiens work appears in music, its use in cinema, the larger-than-expected range of Tolkiens sources, and his influence on other areas both academic and popular, even LGBT studies, which might at first have seemed an unlikely connection, given the response of some critics who deem his work as exclusively heteronormativeand it has much more to say about Tolkien and the twentieth century.

My study looks also at what Tolkien wrote about his own ideas and how he used them in both fiction and scholarship; it considers some cultural loci amidst which he fit without particularly trying. We dont normally think of him for what in many ways he was, whether as fiction writer or scholar, a writer of ideas with great clarity and consistency. Reflecting on himself he didnt characterize himself so, but rather as a storyteller (and as a Catholic, philologist, and family man). Verlyn Flieger has even argued persuasively that we may see in Tolkiens work even elements of the

Next page