About the co-authors

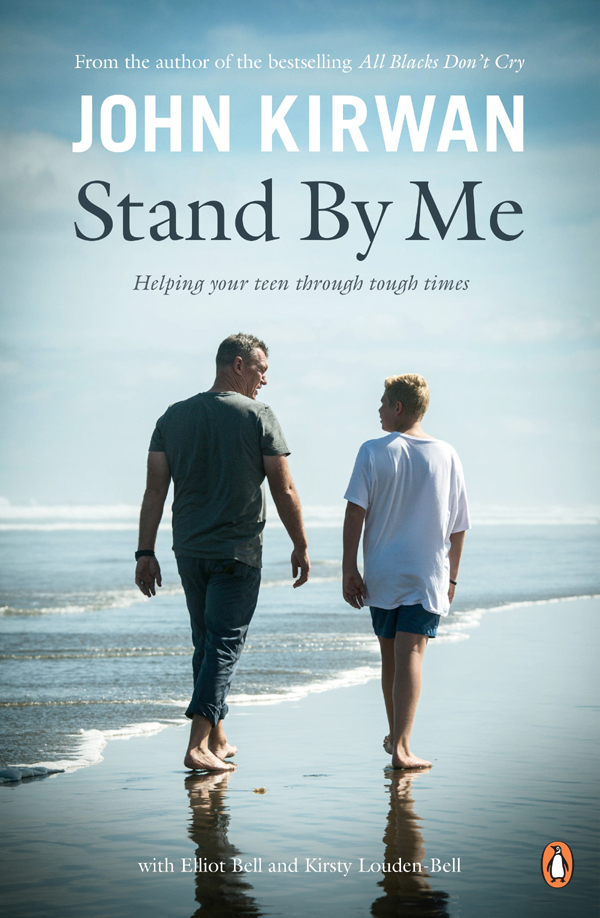

Dr Elliot Bell is a registered clinical psychologist. He trained at Victoria University of Wellington, and has worked clinically in private practice and in local District Health Board mental health services. He currently works as a lecturer and researcher at the University of Otagos School of Medicine and Health Sciences in Wellington, and has a private practice in central Wellington where he sees clients. Elliot is active in the New Zealand College of Clinical Psychologists, currently serving as Vice President. His professional interests include cognitive behavioural treatments of depression, anxiety and schizophrenia; positive psychology; and measurement in psychology.

Kirsty Louden-Bell is also a registered clinical psychologist, and graduated from Victoria University of Wellington in 1995. She has worked in a range of mental health settings in the public sector, as well as in private practice, and has experience in training and presenting, both nationally and internationally. She has a passion for youth and youth work, and since 2001 has been involved through Clinical Advisory Services Aotearoa (CASA) as both a clinician and the manager of a nationwide programme aimed at identifying and managing risk in young people at risk of suicide.

Elliot and Kirsty live in Wellington and have two sons and a daughter.

Margie Thomson has had a long career working in magazines and newspapers, including as a feature writer and books editor for the New Zealand Herald, and feature writer and book reviewer for Your Weekend. She has co-written many books, including John Kirwans All Blacks Dont Cry, Ray Columbuss The Modfather, Malcolm Randss Ecoman, three titles with Kelvin Cruickshank, and with Angela McCarthy The Hungry Heart: Anorexia and Bulimia. She has a Masters in Creative Writing and won the inaugural James Wallace Publication Prize in 2013.

Margie is married to James and has three children. She lives in Auckland.

Prologue

Im a dad and Im scared.

Ive got three great kids who are all teenagers now. I say to my youngest son, How was school today? Good, he says.

I say to my other son, after 45 minutes with the careers counsellor: How was it, mate?

Good!

So what are you going to do for a job?

Too many questions, Dad.

My 19-year-old daughter calls from Italy where shes a professional volleyballer. Shes in tears because shes lonely and wants to come and live with us in New Zealand. We end the Skype call and all I can do is worry.

I had a mental illness, but I still dont know how to parent for mental wellness. I want to parent so that if things are going wrong for my kids Ill see it and know what to do.

Im a solutions guy. Im a rugby coach. If someone isnt playing well I can look at their game and go: his scrummaging or high-ball skills need work. When I was a butchers apprentice I knew how to give the customer what they wanted. If I was a maths teacher I could tell if you didnt understand why x plus y equals z, and I would know what to do to help. But when it comes to guarding the mental health of our children, what are the answers? How do I know whats going on in their heads, in their lives? How do I talk to them?

As part of my research for this book I spoke to a range of young people and their parents or caregivers, asking questions and seeking everyday, real insights.

Sophie: For people our age things are constantly changing. Your relationship with your parents changes. At school your subjects change, your teachers change, your friends are changing and if you fall out with your friend group, youre really in trouble.

Ellen: Your social scene, getting exposed to drugs and things in your social life

Jim: Most people bottle it up and keep it in until it eventually overflows.

JK: The story Ive told about my own mental illness was that it hit me like a truck when I was 23. Out of the blue I had a panic attack. I told no one. I couldnt explain it my life looked so good; I had nothing to complain about. I was lucky! I had no right to be sad: I was an All Black, at the top of my game, Id played really well in the World Cup And in fact sometimes when I played, in that pre-depression period, I felt something like euphoria it was like a massive high before the storm. Yet inside of me I had doubts about how good I was. I was always supercritical of myself. That was part of what made me a good player, but I understand now that it was also out of control, and underneath it all I had a massive fear of failure. I wasnt good enough.