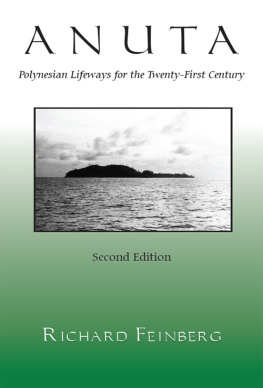

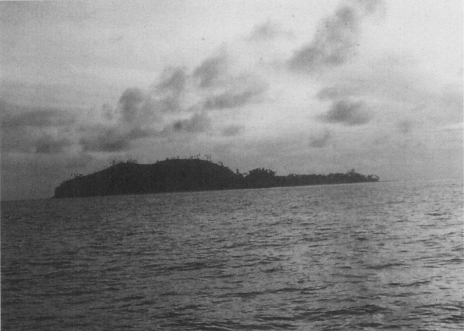

Plate 1. Profile of Anuta at dawn, viewed from the west

POLYNESIAN SEAFARING

AND NAVIGATION

Ocean Travel in Anutan Culture

and Society

Richard Feinberg

THE KENT STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS

Kent, Ohio, and London, England

All photographs used herein are by the author.

1988 by The Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio 44242

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 87-22572

ISBN 0-87338-352-4 (cloth)

ISBN 0-87338-788-0 (paper)

Manufactured in the United States of America

First paper printing, 2003.

The paper in this book meets the guidlines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Feinberg, Richard.

Polynesian seafaring and navigation.

Bibiliography: p.

Includes index.

1. EthnologySolomon IslandsAnuta Island. 2. PolynesiansIndustries. 3. Navigation, PrimitiveSolomon IslandsAnuta Island. 4. Canoes and canoeingSolomon IslandsAnuta Island. 5. Anuta Island (Solomon Islands)Industries. I. Title.

GN 671.S6F46 1988 993'.5 87-22572

ISBN 0-87338-352-4 (alk. paper)

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication data are available.

DEDICATED TO:

PU KOROATU, Anutas senior chief and expert navigator

and

PU NUKUMANAIA, innovator, carpenter, and tau tai par excellence.

Without seafaring canoes, deep-sea sailing skills, and the ability to navigate by naked-eye observations of the stars and sea and bird life, there would have been no Polynesian people as we know them today. These islanders are as much a creation of their voyaging technology as they were creators of it. Had they and their ancestors not developed this technology and associated sailing and navigational skills, the ancestral Polynesians could never have ventured out into the middle of the Pacific to find and settle so many islands and thereby develop into a sizable and culturally distinct people. These islands would have eventually been discovered and colonized, but by other peoples.

Unfortunately, however, the great canoes that once carried Polynesian voyagers from island to island have long since disappeared, along with the traditional skills of sailing and navigating them. The recent realization of this cultural loss has led to major research efforts to comb the journals of the European explorers and other early visitors for information on the canoes they saw and the navigators they interviewed, to use computers to simulate Polynesian voyaging and colonization scenarios, and to reconstruct large Polynesian sailing canoes and then attempt to sail and navigate them in the traditional manner.

While these efforts have been fruitful, they cannot substitute for firsthand experience with an on-going Polynesian canoe tradition. An analogous tradition exists today in the Caroline Islands of Micronesia where from a few atolls seagoing outrigger canoes still sail from island to island guided by navigators skilled at traditional, noninstrument navigation. A number of researchers have taken the opportunity to sail on these Micronesian canoes and to interview their navigators and watch them in action. However, while the information derived has been helpful in interpolating the spotty data on Polynesian voyaging, the experience has also been frustrating for it has made us all the more aware of what might have been learned if a dedicated observer had been able to sail with Polynesian navigators in their heyday.

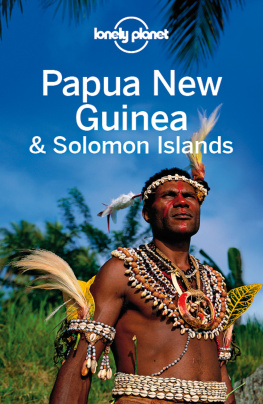

However, Polynesian voyaging researchers have been perhaps a bit too hasty in assuming that there was nothing to be learned in contemporary Polynesia about traditional sailing and navigation. True, the old sailing canoes and their navigators have long been gone from the major Polynesian centers. But there are a few out-of-the-way Polynesian islands where some facets of the old maritime tradition apparently survive today. One such island is Anuta, a tiny volcanic island which, though located within the Solomon Islands of Melanesia, is populated by Polynesians. Because of the small size of the island, its remoteness, and its lack of commercially viable resources, the Anutans there still live close to the traditional pattern of their ancestors. While their Tahitian, Hawaiian, and Samoan cousins may work on commercial plantations, in tourist hotels, or on the military bases of metropolitan powers, the Anutans still farm and fish in the traditional manner. As they still sail canoes in the open sea, using them for short interisland voyages as well as for fishing, this means that they are a living source for information about Polynesian sailing and navigation.

True, the Anutans are not great sailors or navigators. Their canoes are small, and they regularly sail to only one other island, one which lies just over the horizon. Yet, they make and sail their canoes in more or less the same way that their ancestors did, and the sea so pervades their lives that much can be learned of the way Polynesians have adapted to their oceanic environment by looking at how Anutans interact with the sea. But an anthropologist is needed, someone who will go and live on Anuta, learn the language, and then go sailing with the Anutans and listen to their sea stories.

Enter Richard Feinberg, who first went to Anuta in 1972 to spend fourteen months there studying the social organization and kinship structure of the islanders. Feinberg carried out his job well: he learned the language, gathered the data on how Anutan society was organized, and then published a number of works incorporating his findings. Although sailing and navigation were not his research focus, as a person who enjoyed being on or near the sea, Feinberg found himself drawn more and more to talking with Anutans about their voyages to other islands, and to going to sea with them in their canoes. Feinberg was, in other words, hooked, and in subsequent trips to Anuta and nearby islands he focused his inquiries on canoes, fishing, and navigation.

The result is this intriguing study of Anutan seafaring and navigation. In addition to the expectable descriptions of such things as canoe construction and sail handling, Feinberg has provided us with analyses of unknown or little known facets of Anutan maritime culture which are relevant to our understanding of the general Polynesian adaptation to the sea. For example, his inquiry into the symbolism behind the fashioning of canoe prows in the form of a birds head sheds light on this apparently common though little understood Polynesian practice. His description of how Anutans combine sailing on one tack and then paddling on the other to move upwind provides a new perspective on the general problem faced by all Polynesian mariners of making their way to windward. Similarly, Feinbergs analysis of the interisland voyages Anutans could recall informs us about motivation, success rates, survival, and other crucial aspects of interisland voyaging. While the Anutan canoes may not be as large or elaborate as the great double-canoes of an earlier age, and while the Anutan sailors and navigators may not seem as heroic as those who once sailed in Polynesian waters, Feinberg has skillfully delineated the role of seafaring in Anutan life and in so doing has given us some rare insights into the larger picture of how Polynesians have adapted to the sea.