ANUTA

Second Edition

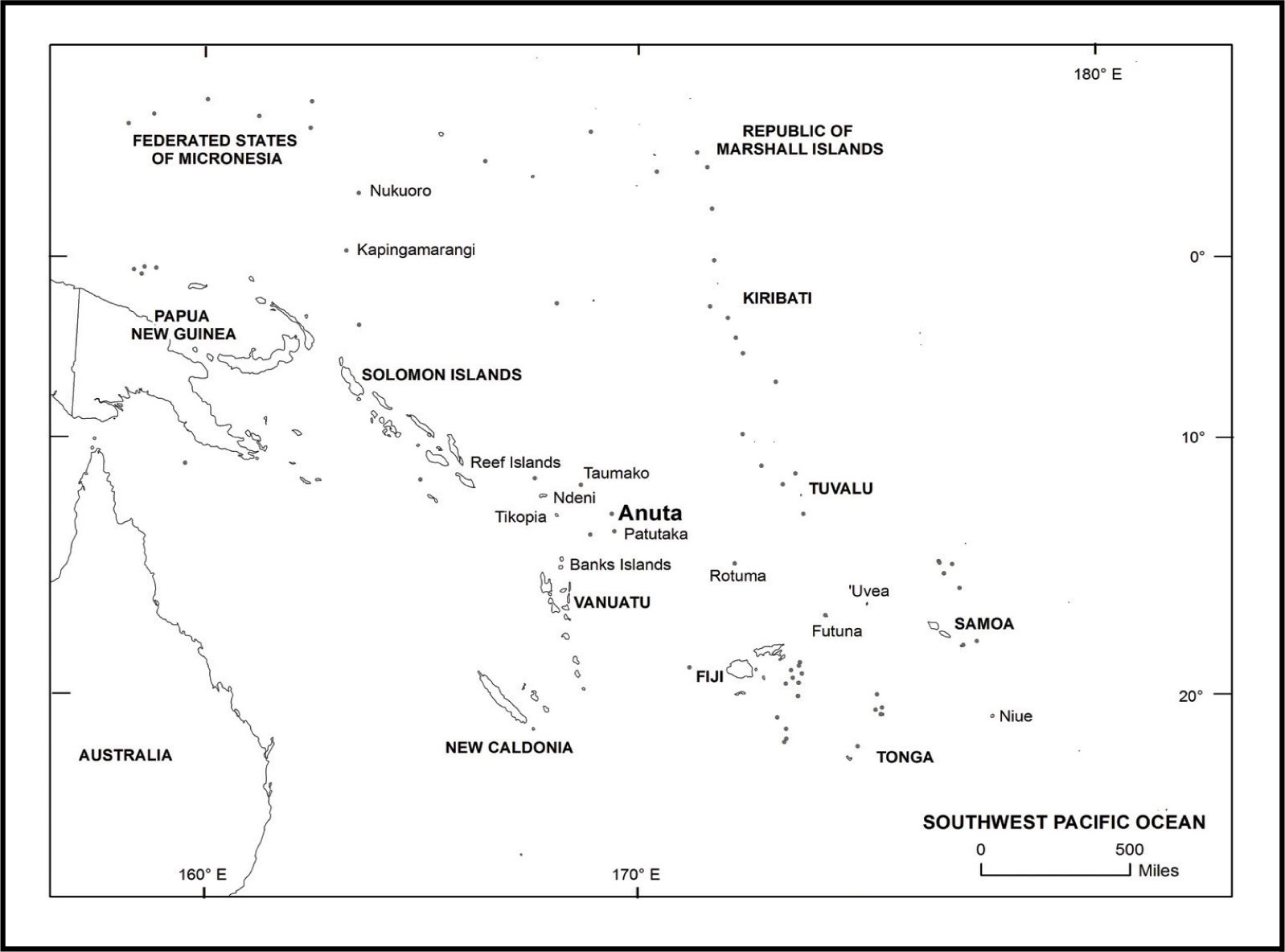

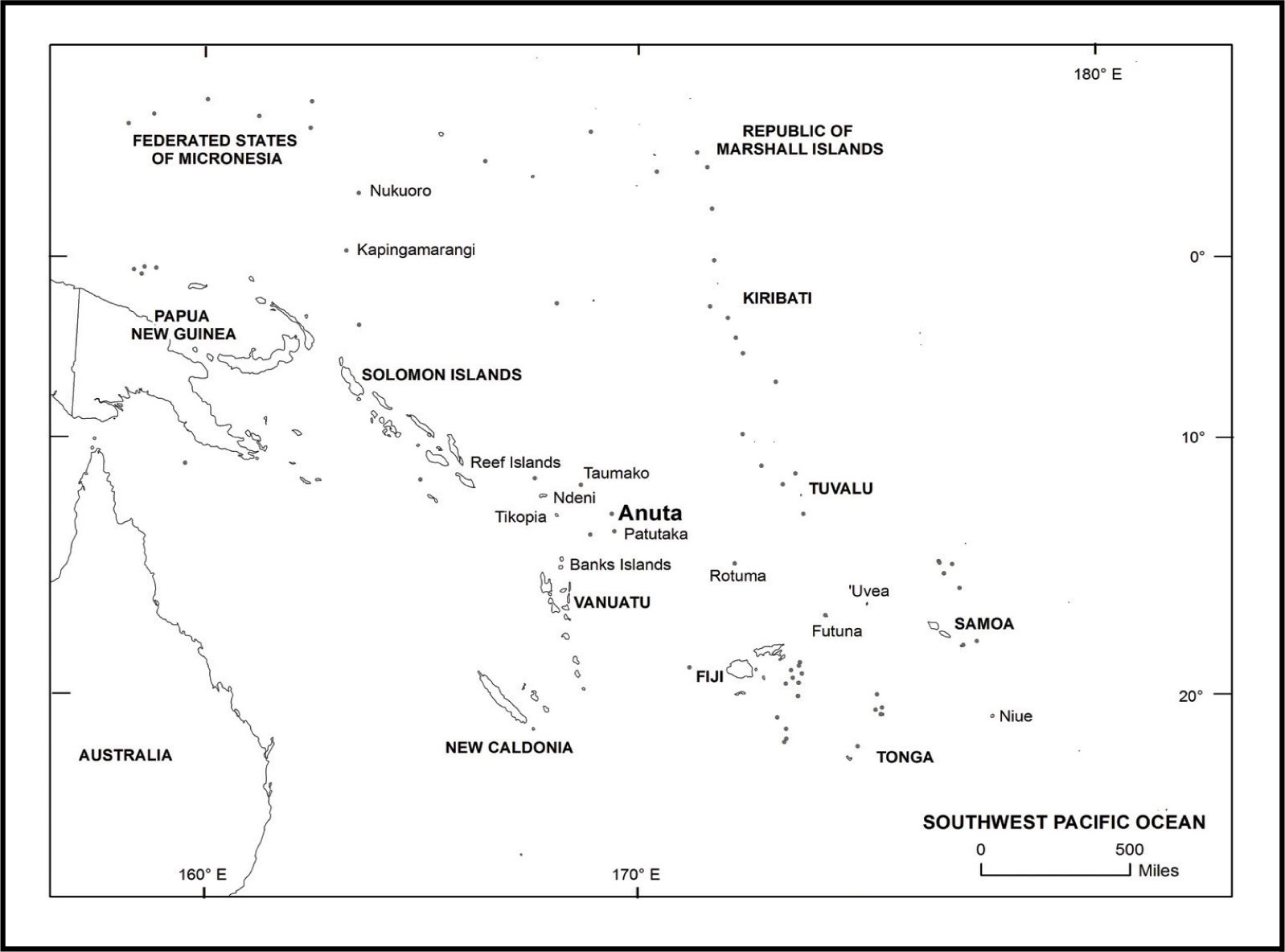

Map of Central Pacific Ocean, showing relationship of Anuta to other islands and island groups.

ANUTA

Polynesian Lifeways for the 21st Century

Second Edition

R ICHARD F EINBERG

Kent State University

The Kent State University Press

Kent, Ohio

Copyright 2011 by Richard Feinberg

Published by The Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio 44242

www.kentstateuniversitypress.com

All rights reserved

Previously published in 2004 by Waveland Press, Inc.

ISBN 978-1-60635-139-0 (paper)

ISBN 978-1-61277-478-7 (EPUB)

ISBN 978-1-61277-479-4 (ePDF)

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available.

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication data are available.

Dedicated to

the Memory of My Parents,

Dr. Rose S. Hartmann Feinberg and Dr. Isadore (Tex) Feinberg.

For the unfailing emotional and intellectual support that made this work possible.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many people have contributed in countless ways to the creation of this book. Most critical are my Anutan hosts who welcomed me to their island, adopted me into their community, and taught me everything I know about their way of life. Special thanks are due to Pu Paone; senior chief Pu Koroatu; the chiefs brothers Pu Tokerau and Frank Kataina (Pu Teukumarae); and John Tope (Pu Avatere) for their friendship, hospitality, and assistance over a period that has spanned three decades. Pu Nukumarere and Moses Purianga generously shared their prodigious knowledge of Anutan genealogy and oral tradition, and Pu Nukumanaia was my most important teacher of navigational lore. Sister Lilian Takua Maeva dedicated her life to helping others through devoted service to the Church of Melanesia. She courageously intervened to help calm the civil war that devastated the Solomon Islands in 1999 and 2000, and she died suddenly while organizing cyclone relief for people of the eastern Solomons in 2003. Her contribution to this book is diffuse but nonetheless profound. Other Anutans facilitated my research and saw to my comfort and well-being in ways too numerous to mention; my debt to all of them is beyond measure.

To the late Sir Raymond Firth I owe my choice of Anuta as a research site. His intellectual guidance and support continued unabated from the time that he suggested Anuta as a focus for my investigation until his death in 2002.

My initial study of Anuta was funded by a graduate student training grant under the auspices of the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health, administered by the University of Chicagos Department of Anthropology. Several subsequent periods of field research were sponsored by the Kent State University Research Council, the universitys Faculty Improvement Leave program, and Kent States Anthropology Department.

Most of the material in chapters first appeared in a volume entitled Anuta: Social Structure of a Polynesian Island, published in 1981 by the Institute for Polynesian Studies at Brigham Young Universitys Hawaii campus. I am indebted to the Institute and its director, Dale Robertson, for cooperation and encouragement in the production of this volume.

I must thank Tom Curtin of Waveland Press for taking on this project. Don Rosso has seen me through the copyediting and production process. This book is much the stronger for his patience, care, and thoughtful guidance.

Finally, I owe my family a debt of gratitude that words alone cannot describe. My parents, Dr. Isadore Feinberg (19221978) and Dr. Rose S. Hartmann Feinberg (19182001) helped shape my sense of curiosity, my interest in understanding human relationships, my attraction to the sea and tropical islands, and my appreciation of the natural environment. Their unwavering supportemotional, material, and intellectualwas indispensable to my success in school and my initial foray into Pacific research. My wife, Nancy Grim, and children, Joe and Kate, accompanied me to the field in 198384 and 1993, and they put up with absences of many months in 1988 and 2000 while I pursued my ongoing investigations. Their interest in my research and writing has been a source of constant inspiration.

To all those mentioned here, and to others who have helped enrich my life of anthropological scholarship, I say tangi pakaaue; toku aropa ki a kotou kairo oti (I call out in gratitude; my affection for you all is beyond measure)

.

Chapter 1

Introduction to Anuta

I stood on the deck of the Solomon Islands government ship Kwai and strained my eyes against the early morning mist. Anuta, the island that would be my home for the next year, had just appeared on the horizon. Its outlines gradually came into focus: first the rounded hill that occupies its northern section, then the low-lying coastal flat, and finally the beach and fringing reef.

I knew Anuta would be small, but this was a mere specka half-mile in diameter and 75 miles from its nearest populated neighbor. We sailed around the island once, then anchored several hundred yards offshore. An outrigger canoe soon pulled aside the ship. Several men, clad only in bark waist-cloths, swam out from the beach. After a few moments of animated conversation, which I endeavored unsuccessfully to follow, a group of passengers disembarked in the canoe.

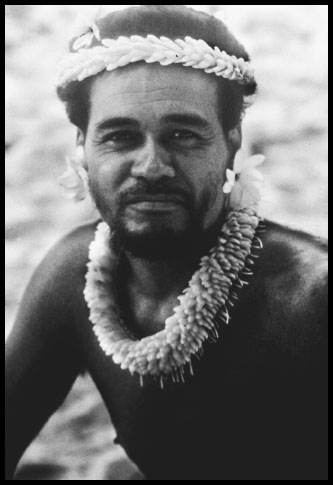

Amid the pandemonium, one of the swimmers clambered to the deck and introduced himself to me as Matthew. When he ascertained that I was planning to stay on the island, he proclaimed that he would be my friend and insisted that I follow him. The mans Anutan name, I later learned, was Pu Paone, and he was among the islands most distinguished leaders. True to his word, he quickly grew to be one of my closest friends and most important teachers of Anutan custom.

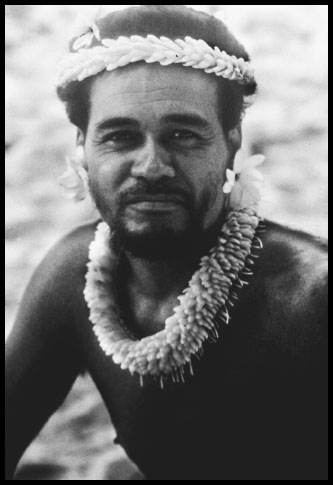

Photo 1.1 Pu Paone, authors close friend and community leader.

Soon others crowded around. One young man seemed particularly agitated. He seated himself on the deck in front of me and started shouting in a language that I could not understand but took to be Anutan. I struggled to make sense of what was going on, but his companions told me to ignore him. They explained that he was karange (cranky) and believed himself to be addressing me in English. Karange is a word in Pijin, a kind of pidgin English spoken throughout the Solomon Islands, and it refers to someone who is mentally incompetent.

In the space of a few minutes I had met the most and least admired of my soon-to-be compatriots. Meanwhile, Pu Paone slipped away, and the ships crew decided that the supposed dignitariesthe colonial district officer, a police sergeant, and Ishould go ashore in the launch. Clutching my camera case and a small bag of irreplaceable papers, I descended into the little boat and hoped for the best.

The few published descriptions of Anuta (particularly ) mentioned a very narrow channel through the reef. I soon discovered that there was no channel if that is taken to mean a deep-water opening. The so-called passage was simply an area where the surf beat a little less fiercely than elsewhere, and we headed toward that spot. One crew member stood in the stern and propelled us with a long sculling oar; two others stood and paddled in the bow. We reached the breakers, tried to surf behind the crest of a large wave, and almost made it to the beach. When we were perhaps fifteen yards from shore, another wave caught up with us, swept across the transom, and completely filled our boat. I grabbed my bag of papers and managed to keep it out of the water while calling out, the camera! A member of our party quickly retrieved the vinyl bag, and the equipment survived with surprisingly little damage despite several seconds of immersion. I had been warned that landing on Anuta could be an adventure, and the event lived up to its billing.