End of Life Care for People with Dementia

A Person-Centred Approach

Laura Middleton-Green, Jane Chatterjee, Sarah Russell and Murna Downs

Jessica Kingsley Publishers

London and Philadelphia

Contents

Introduction

You matter because you are you, and you matter to the end of your life. We will do all we can, not only to help you die peacefully, but also to live until you die.

Dame Cicely Saunders, physician, social worker, nurse and writer, and founder of the hospice movement (19182005)

WHY IS THIS BOOK NEEDED?

The demographics of the population of the United Kingdom are changing. As medical knowledge advances, including public health screening programmes and preventive medicine, we are living longer. This is something to be celebrated, but it is not without its cost.

Humans are living for longer. Advances in medicinal diagnosis and treatment mean that life expectancy for a baby born in the UK, in 2015, is 78 for men and 82 for women (ONS 2015). The number of people being diagnosed with dementia has increased accordingly and is predicted to continue to expand. In 2013, there were 815,827 people with dementia in the UK, of whom 773,502 were aged 65 years or over; 1 in every 14 of the population aged 65 years and over will be diagnosed with dementia (Price et al. 2014). Fifteen per cent of all deaths between 2001 and 2009 were attributable to dementia (NEoLCP 2010); this is a significant proportion. The majority of people with dementia in the UK die in care homes where the complexity of care and challenge of fragmentation makes service provision difficult (Kupeli et al. 2016a).

It is impossible to imagine that traditional models of specialist palliative and hospice care will be available to all people living and dying with dementia. In fact, not all people in this situation will require specialist intervention. For many people dying with dementia, their needs are basic human requirements that can be achieved in any appropriate setting where intention, competence and confidence are supported. This book is about how to do this it is not aimed at specialists, but at professional care providers and perhaps families who want to know how to achieve the best dying and death for the person they are caring for.

THINKING ABOUT DEATH

In a society that prides itself on medical advancement and ever-increasing standards of living, it is unsurprising that we generally avoid thinking about death (Dying Matters 2012). For example, manifestations of a death-denying culture are seen in hospital wards where patients who are dying are moved to side rooms for peace and quiet, hidden from general view. Healthcare staff adopt hushed tones, and when the inevitable does occur, the finest china tea service is brought from the ward kitchen cupboard for the event of breaking bad news to families and loved ones. Medical interventions are advancing at a phenomenal pace, such that it has become increasingly difficult in the Western world to die a death unencumbered from clinical interventions. So much so, there is competition for the ownership of a good death. Some campaign tirelessly through the cause of assisted suicide for the ability to choose the timing and manner of our own departing, whilst others advocate an increase in hospice and palliative care services.

But death in itself is not good or bad it is merely the certain ending of the life that we have begun. Regardless of spiritual and religious beliefs pertaining to what happens next, we will all die. This does not need to be a morose topic of thought. Some faiths advocate thinking regularly about our own death and the death of our loved ones as a vehicle to reduce anxiety of the inevitable.

An ageing population has consequences for a wide range of services, and it is necessary for those services to evolve to accommodate the unique needs of the population. As people age, they are more likely to experience a range of health issues (Barnett et al. 2012). Barnett et al. (2012) further identified that as the likelihood of having a mental health disorder increased, so, too, did the chance of having a physical health problem. Whilst we do not intend to adopt a problem-orientated perspective in this book, it is an important consideration that a model of single disease-specific interventions is no longer appropriate. For those people currently living with dementia in the UK (Alzheimers Society 2012), the future is uncertain. Decisions will need to be made about where they will live, how they will be treated and who will speak on their behalf when they become unable to communicate for themselves. It is a frightening prospect.

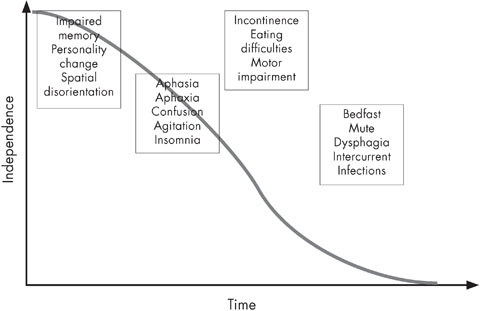

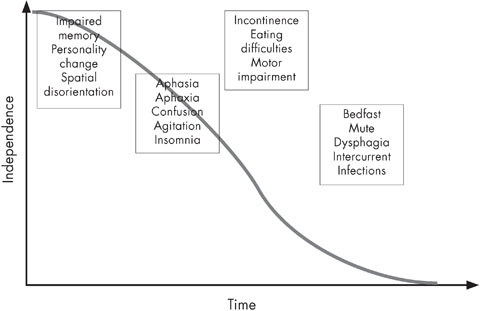

Dementia is not a single illness. In the UK, the Alzheimers Society describes dementia as an umbrella term for a set of symptoms that may include memory loss and difficulties with thinking, problem-solving or language. There are many different types of dementia, and neither are people all affected in the same way. People dying with dementia may exhibit a range of complex needs contingent on their individual constitution, social and demographic factors, the nature of their illness and the existence of comorbidities. These needs will inevitably change over the course of the illness, as illustrates.

The fact that dementia is a progressive, incurable life-limiting illness is not always raised. This is curious, as the typical illness trajectories of steady progression with a clear terminal phase (e.g. cancer), gradual decline with acute episodes (e.g. organ failure) and prolonged gradual decline (e.g. dementia and frail elderly) has been well described in the literature since Lynn and Adamsons (2003) seminal work about living well at the end of life. Perhaps because of dementias prolonged prognosis, discussions about the end of life (however defined) are seldom initiated by health professionals early on. A healthcare model focused on cure means that many well-meaning professionals may not wish to draw attention to this aspect of the illness, concentrating instead on opportunities for treatment and care.

Figure 1.1 The changing needs of people with dementia over time

Source: Adapted from Volicer and Hurley (2004)

The fact remains that everyone will die. Some will die suddenly, without an opportunity to plan or for their loved ones to prepare. Others will experience physical illnesses such as cancer or a chronic respiratory disease, which ultimately leads to the breakdown of the physical self until the body can no longer sustain life. People with dementia may also die in these ways, but many die of the complications of advanced dementia itself: acquiring multiple infections, experiencing falls, or aspirating food through a diminished ability to swallow. This book is written for these people.

The prognosis of people with advanced dementia following acute illness is known to be poor. For example, Morrison and Siu (2000) examined the six-month survival rate of patients with dementia following admission to hospital with two common acute conditions: hip fracture and pneumonia. High levels of mortality within six months of admission were identified: 53 per cent for patients with pneumonia, and 55 per cent for patients with hip fractures. Morrison and Sius research also identified an additional worrying trend there was no written evidence relating to goals of care, such as decisions to withhold or withdraw life-prolonging treatments such as antibiotics. Decisions relating to cardiopulmonary resuscitation were invariably made when the patients were comatose or hypotensive and approaching death in acute hospital settings.

Next page