M y dad walked onto the stage in the high-school gymnasium carrying a cut-out of a tombstone.

A giant of a man in a grey suit, he looked out at the rows and rows of students assembled: his students, the young men and women at the school where he was principal, the adolescents he hoped to inspire and lead toward opportunity and success. My dad stood on that stage in his grey suit, looking for all the world like Morgan Freeman in the movie Lean on MeI swear, looking back, I can almost hear Axl Rose belting out Welcome to the Jungle. Because thats how I still see him, my dad: staring down any rough elements, wanting to be everything he could be to those kids.

He was up there, larger than life, showing no sign of the strain of running a large school. His face bore no hint of his worries for his students prospects. He looked at those hundreds of young people with their whole lives stretched out before them, and he waved that tombstone, and he shouted out, in a voice that filled the gym: Whats the most important part of this?

I was in middle school, maybe twelve years old, hanging around at his high school for the day, as I often did when there was a PA day at my own school in Scarborough, Ontario. It wasnt unusual for me, on such a day, to find myself in a gym full of high schoolers. My dad was one of those principals who liked holding assemblies: he really liked bringing his kids together. I looked around me. Those students, all older than I was, thought the answer was easy.

They shouted back: The day you were born!

They screamed out: The day you die!

They yelled: Your name!

My dad was like that: he could really grab a room. Even this gymnasium full of what might have been restless, unruly students. Now that he had them, he told them what he most wanted them to hear: No, he told them. (Told us, I should say. I was caught, too, just like the kids around me, hanging on his every word.)

Its not what you think, he said.

The most important part is the smallest part. The dash. The time you spend on this earth. All the years that come between the two dates are compressed in that dash. And that has to count. It has to mean something. You have to leave some mark in life.

What we have to consider is that were here for a purpose. We have to find that purpose, and not let people or events deter us. We have to push forward and progress. And thats all part of the dash.

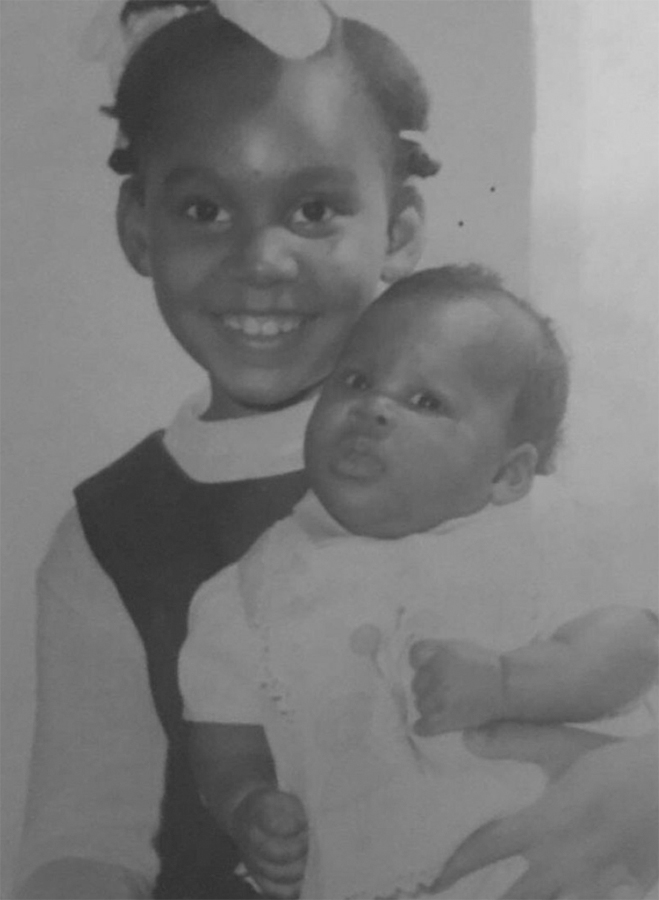

That day was nearly forty years ago, but Dads message, seeing him up there and the pride I felt, has never left me. I even named my son Dash. He fits the bill. Hes a bright light. He moves quickly and fearlessly. (My daughter, Blaize, lives up to her fiery name, too. I named her after the word trailblazer.) My dad is like me: he doesnt use notes when he speaks. He gets his thoughts together, looks for inspiration. Then he freestyles. Back then, hed come across Linda Elliss poem The Dash, which has become famous because of its message about the true value of a life. He incorporated that idea into his speech. But heres the beauty of Dads thinking. The Dash was written as a funeral poemit was about looking back. He read that poem with its powerful message, thought it over, and switched it around. He made it not about the end of life but the beginning.

What are you going to do with your life? What kind of mark will you leave?

When Dad spoke of the mark we leave, he didnt just mean purpose and goals. He spoke of the people in our lives who make reaching for those goals possible. To his students he spoke especially of parents, caregivers, guardians. The people who make sacrifices every day in order to be there for you and give you what you need. Remember that they want the best for you, he told that gymnasium full of students, that crowd of kids that included me.

Part of using your time well, he said, is being grateful for what you have, and even more so, who you have. Time is something you cant take for granted, absolutely. And the people you have with you during your time? You cant take them for granted either. So how about saying thanks to your parents for breakfast? Remember to say thank you to them for all that they do.

Heres what Ive found: the further in life I get, the more thank yous I need to say.

Ive been thinking, lately, about what my dad said that day. About legacy. Purpose. My time here. How Im using my microphone. What it means to have it. And especially about the people in my life whove made it possible for me to be who I am and do what I do.

In 2010, when the Olympic Winter Games came to Vancouver, I was a news anchor for CTVs national morning show, Canada AM, for which I would later serve as co-host for six years with Beverly Thomson and Jeff Hutcheson. When it comes to the Olympics, the whole network kicks into gearnews, sports and entertainment divisions. I was called to duty as well: I was sent to Halifax to take part in the Olympic torch relay.

The location was no accident. Bev had started her career in Belleville, Ontariothats where she was sent to carry the torch. Co-host Seamus ORegan (now a Liberal MP), carried the torch in his home province, Newfoundland and Labrador. Jeff represented western Canada and carried his torch in Langley, BC. Halifax was my citywhere Id landed my first job with the network, as a reporter for CTV News in 1997. It was there that Id covered major tragedies such as the crash of Swissair Flight 111 off Peggys Cove, and stories close to my heart such as the legacy of Africville, the Black Halifax village that was demolished in the 1960s, a blot on Canadian history.

It was amazing, absolutely amazing, to return to Halifax to be part of this Olympic ceremony. I felt a lot of pride to represent my country this way. My husband, Lloyd, and our daughter, Blaizeshe was only five years oldflew east with me: this opportunity was too exciting to miss. We planned to spend a family weekend in Halifax afterward. We checked into our hotel and, as instructed, I went to meet the organizers and other participants near Citadel Hill. It was late November, cold and grey. As the relay was about to get underway, we were given our instructions and special clothing, which included a white hat and track suit and red woollen Hudsons Bay Olympic mittens. Then we all dispersed to our appointed spots on the route.

Once the torch was handed off to you, you could walk, run or jog. The key was that you were to do your part of the route solo: youre the torchbearer; its only you.

I chose to walk. So I was right in downtown Halifax, marching down the street, torch in hand. It was long and slim, made of this hard, slippery plastic. The flame atop it burned bright. The streets were lined like a parade route. There were loads of people. Lloyd and Blaize had set up in a spot where I would pass them. All of a sudden I heard, Momma! Momma! I turned, and there was Blaize, bundled up in her pink scarf and furry boots. Shed spotted me, and she was shouting for all she was worth.

An RCMP officer heard Blaize calling, went over to her and with Lloyds permission walked her over to me. I smiled at himgrateful for his kind gestureand held her hand with my left while gripping the torch with my right. And she walked with me. I was worried; the torch was so slippery, I thought it would slip from my mittened hand. But it didnt. And we finished my leg of the relay together.