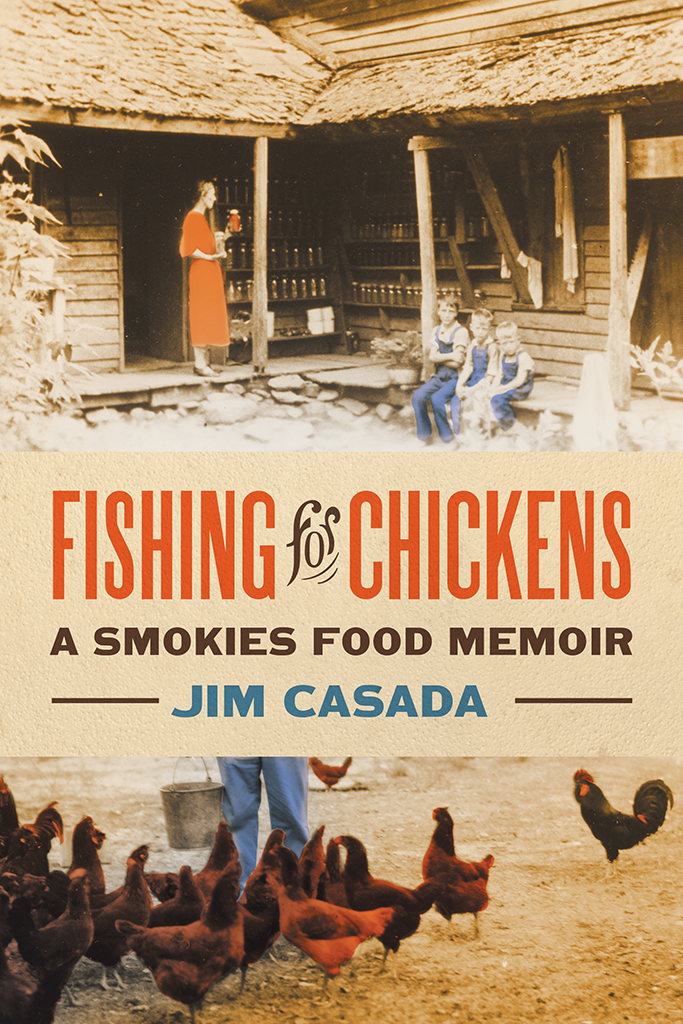

FISHING FOR CHICKENS

FISHING for CHICKENS

A SMOKIES FOOD MEMOIR

JIM CASADA

THE UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA PRESS

ATHENS

Published by the University of Georgia Press

Athens, Georgia 30602

www.ugapress.org

2022 by Jim Casada

All rights reserved

Designed by Lindsay Starr Set in Warnock Pro and Unit Gothic Printed and bound by Sheridan Books

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Most University of Georgia Press titles are available from popular e-book vendors.

Printed in the United States of America

22 23 24 25 26 P 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Number: 2022932776

ISBN: 9780820362120 (paperback)

ISBN: 9780820362113 (ebook)

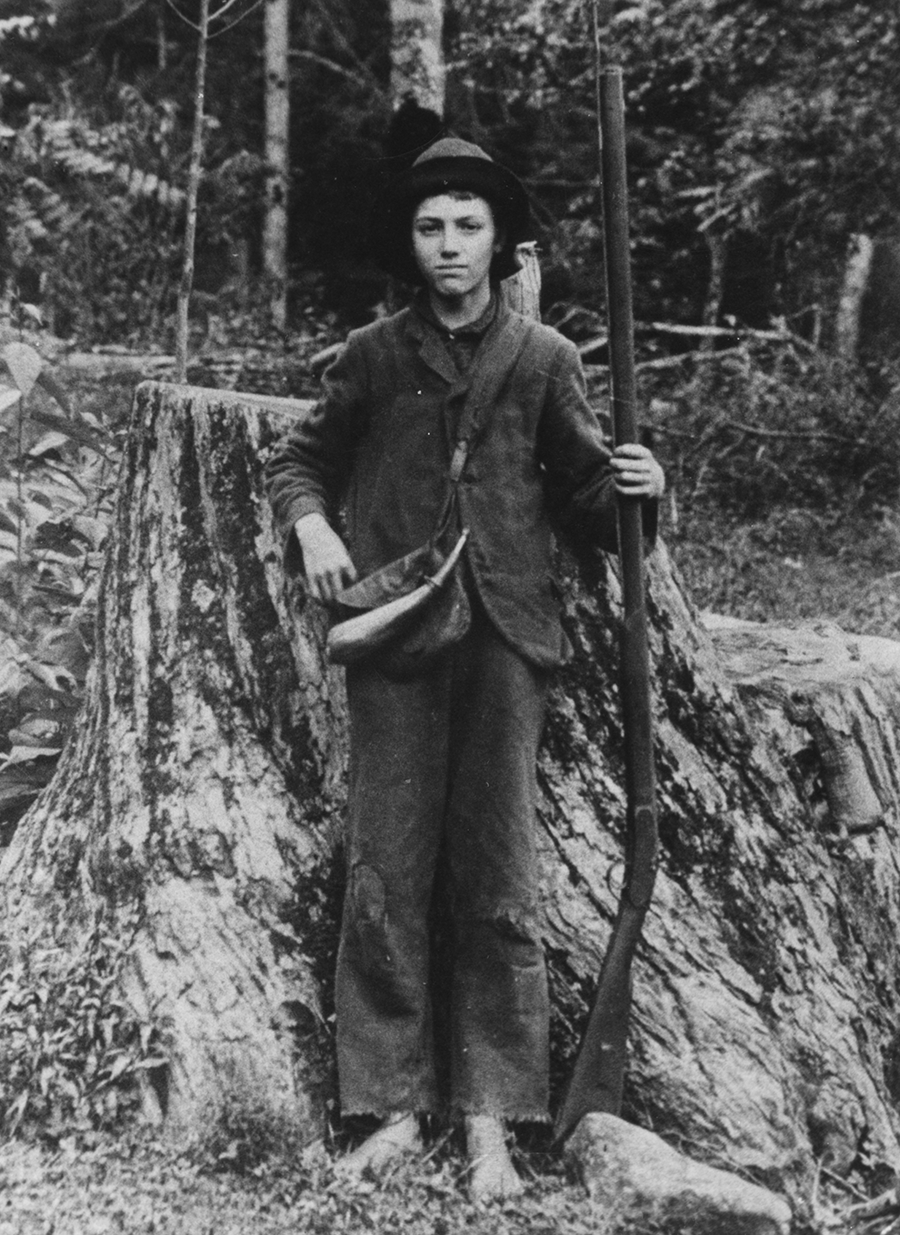

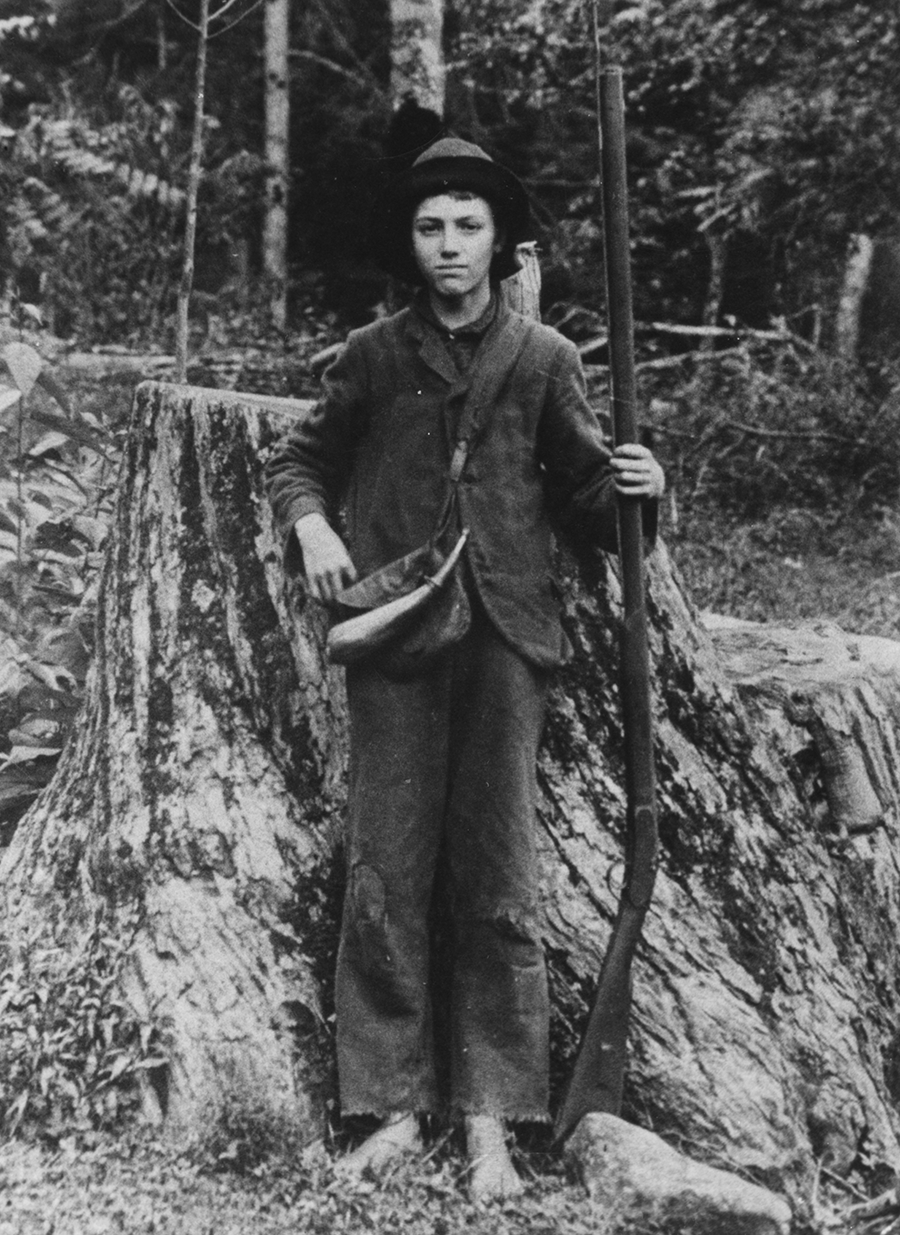

: A barefooted young hunter with a long rifle, powder horn, and possibles bag. Hunting, primarily for bears, wild turkeys, and small game, was an importantpart of daily existence and diet for many who lived in the Smokies.

Courtesy of the National Park Service.

: John Wade prepares to butcher a hog suspended from a gambrel.

Courtesy of Hunter Library, Western Carolina University.

To the memory of the three finest cooks Ive ever known, my paternal grandmother, Minnie Casada; my mother, Anna Lou Casada; and my late wife, Ann Casada. All were self-taught culinary wizards, loving souls, and in the case of the first two, wonderful mentors when it came to the mystery and magic of mountain cooking. Both Momma and Grandma had traumatic childhoodsGrandma Minnie was indentured or bound, something that still existed in the late nineteenth century, while as an infant Momma lost her mother, and her peripatetic father essentially left others in the family to raise her. As a result, Mommas youth was so filled with moves from one place to another that when she and Daddy married, bought a home, and settled down in Bryson City, her heartfelt statement was: I never want to move again. For well over a half century, until the final weeks of her life, when the ravages of Parkinsons disease forced her into a nursing home, she never did.

For these two women, cooking became an expression of who they were, a means whereby they could simultaneously exercise creativity and convey love to others, and an activity that gave them a great deal of quiet satisfaction. Seldom does a day pass when I dont think of one or both of them, and rarer still are the times when I prepare or eat some traditional mountain dish without them coming to mind. Even after the passage of decades, I miss them terribly, but their influence in the form of mountain fixings and a great deal more remains as powerful and persuasive as ever.

As for Ann, at the point when we married, she was singularly inept in culinary matters, but she was a quick learner and absorbed mountain food wisdom like cornmeal soaking up buttermilk as batter is being prepared for a pone of cornbread. She also read voraciously and within the first decade or so of our marriage had easily surpassed me in terms of actual in the kitchen skills, although as a daughter of the Southside Virginia soil, she obviously lacked the deeply rooted link to mountain food folkways I had been exposed to from earliest memory. She was my stellar and skilled partner in a number of cookbooks, and her influence, while largely intangible, permeates these pages just as that of Grandma Minnie and Momma does.

CONTENTS

While this cookbook is dedicated to my grandmother, mother, and wife, I would be remiss if I failed to mention others who have, in varying ways, made a meaningful impact on my long-standing interest in Smokies foodways.

Foremost among those individuals is my webmaster, distant cousin, and cherished friend, Tipper Pressley. A mountain cook in the finest tradition of the kitchen arts, she occasionally teaches classes in the subject at John C. Campbell Folk School. More significantly, her daily internet dose of Appalachian culture, Blind Pig and the Acorn, regularly features recipes and food lore. For years Ive pestered her to put her boundless wisdom into a cookbook, and hopefully someday she will. Anytime I get stuck on something to do with cooking, I know I can turn to her with every expectation of receiving a helpful answer.

A number of friends have assisted me, knowingly and otherwise, with useful information. Larry Proffitt, the owner of famed Ridgewood Barbecue in upper east Tennessee, is not only a cherished friend and good turkey hunting buddy, he is the man when it comes to anything connected with hickory-smoked hog. How many little restaurants stuck in the middle of nowhere on a Tennessee back road have been the subject of a book (Fred Saucemans The Proffitts of Ridgewood)? Whenever I talk with or have an email from Craig Stripling, a genial Texan who shares my love of foodlore, my spirits lift perceptibly, and when he comments that some recent dish was larruping good, Im reminded of the fact that food talk is not limited to the geographical confines of my beloved Smokies. Delia Watkins, a powerful link to foodways of yesteryear whose culinary skills were well known on the local scene, graciously shared her memories. The influence and recollections of other fine cooks also figure in these pagesmy aunt Emma Burnett; venerable Maggie Aunt Mag Williams, a beloved Black neighbor from my boyhood; Beulah Sudderth, a Black cook of the next generation after Aunt Mag whose love affair with food and cooking was an inspiration; and extended family members who always had something special for summertime family reunions. Others who shared insights or food memories include Bunny Burnett and her late husband, Bill, along with cookbook author and lifelong friend Sue Hyde and high school classmate and good friend Maxine Freeman Skelton.

Family ties underlie this entire work, and they extend from those no longer with usmy parents, paternal grandparents, and a bunch of aunts and unclesto those who still savor mountain fare and food memories, including my siblings, Don Casada (and Dons wife, Susan) and Annette Hensley, along with first cousins James Burnett and Carolyn Healy. My brother and sister reinforced and/or expanded recollections of all sorts of food-related aspects of daily life, and my cousins have been able to shed considerable light on the lives of our paternal grandparents. My daughter, Natasha, has been a steady cheerleader and on more than one occasion has made my day with words such as its gratifying to know the old man can still work in a hard and productive fashion.

Finally, at every step of the process from initial inquiry about the manuscript forward, staff at the University of Georgia Press have been gracious, helpful, and prompt (something that is not always the case with academic publishers). I owe them a genuine debt of gratitude, and special praise is due to Nate Holly, the acquisitions editor with whom Ive worked closely throughout the project. His enthusiasm, prompt responses to any and all questions, and willingness to deal patiently with a technological troglodyte have been gratifying indeed. Similarly, Jon Davies, managing editor at the Press, has been timely in his responses and admirably professional every step of the way. Courtney Denney, the copyeditor who handled my manuscript, not only did a stellar job in righting my literary wrongs but was a distinct pleasure to work with as well.