The biblical quotations in this book come from The Authorized Version of King James I, produced by the British and Foreign Bible Society and printed at the University Press, Oxford (copyright 1928).

All contents and photography copyright 2009 by Kitty Morse and Owen Morse. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, except brief excerpts for the purpose of review, without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN-10: 06152763511

ISBN-13: 978-0-615-27635-9

Layout Design by Kimbrel Designs

ALSO BY

KITTY MORSE

Come with Me to the Kasbah: A Cooks Tour of Morocco

The California Farm Cookbook

365 Ways to Cook Vegetarian

Edible Flowers Poster

Edible Flowers: A Kitchen Companion

The Vegetarian Table: North Africa

Couscous: Fresh and Flavorful Contemporary Recipes

The Scent of Orange Blossoms: Sephardic Cuisine from Morocco

Cooking at the Kasbah: Recipes from My Moroccan Kitchen

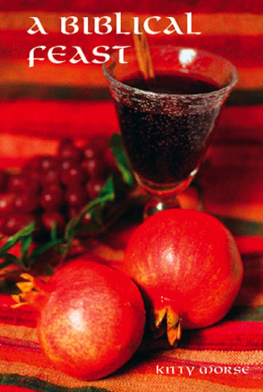

Accolades for the first edition of

A Biblical Feast:

Foods from the Holy Land for Today

A Biblical Feast is more than a standard how-to book. Part history lesson, part cookbook, it weaves together stories from the Bible with exhaustive definitions, explanations and directions not only on how to cook, but also how to understand the food people ate. A Biblical Feast reminds us that the Bible is not just a holy text. It is also an ethno-historical text that gives modern readers a window onto the past.

Austin Chronicle

With the recipes as a starting point, you can explore the Bibles culinary heritage. Maybe youll even get carried away and invite guests and family members to dine Bible-style: sitting or reclining on the floor, eating from a communal dish with the fingers, leaning against one another in reflection and celebration.

San Jose Mercury News

Kitty Morse offers a gentle, lovely view of the spirituality of food

in the Scriptures.

Food Day, The Post Courier

CONTENTS

A BIBLICAL FEAST

He watereth the hills from his chambers:

The earth is satisfied with the fruit of thy works.

He causeth the grass to grow for the cattle,

and herb for the service of man:

that he may bring forth food out of the earth;

and wine that maketh glad the heart of man,

and oil to make his face to shine,

and bread which strengtheneth mans heart.

Psalms 104:13-15

To travel through the rural regions of my native Morocco is akin to being transported back to biblical times. Small farmers work the land in much the same way as their Arab and Berber forbears centuries earlier, plowing with camels or oxen, while sowing, cultivating and harvesting by hand. Women and children watch over small flocks of sheep and goats, carry amphorae from nearby wells and gather firewood to fuel their mud ovens. Once a week, farmers clad in traditional djellabahs, sandals and turbans haul their produce to the local souk in woven straw baskets slung heavily over the backs of submissive donkeysa biblical tableau come to life.

As a schoolgirl, I prepared for my confirmation at the quaint Anglican Church of Saint John the Evangelist, an island of tranquility in the heart of Casablanca, Moroccos bustling commercial capital. Somehow, I never considered the similarity between the way of life of the ancient Semitic tribes I was studying in the Bible and the culture of the people living just beyond the city limits.

Years later, while attending an Easter service, I listened to a thought-provoking sermon taken from John 13:20-30. The realization suddenly struck me: Jesus and the disciples dined la marocaine (Moroccan style), or, more accurately, in the popular Greco-Roman style of their day. In his famous wall painting of the Last Supper, Leonardo da Vinci created a misconception that persists to this day, by portraying the celebrants seated on chairs along one side of an elegant, linen-covered banquet table in a spacious, Renaissance-style refectory.

It is far more likely that on the last Passover of His life (the last Feast of Unleavened Bread), that Christ gathered with His disciples in the guest chamber of a modest dwelling in Jerusalem. After taking part in a ritual hand washing (customary when eating from a common dish), they took their places on straw mats, rugs, cushions or divans around a low table. There they reclined, as free men would, casually leaning against one another as they passed a cup of red wine, symbolic of the lambs blood shed twelve centuries earlier for the salvation of Israels firstborn sons.

A fire-roasted lamb prepared for the occasion also reminded them of this ancient sacrifice. With fingers as their only utensils, they plucked charred, yet succulent pieces from the tender roast. Following a brief interlude in which Jesus washed the feet of His disciples, everyone continued with the ritual meal. They dipped twisted bouquets of bitter herbs into salted water in remembrance of the bitterness and tears of Pharaonic bondage, as Jesus might have done when He offered the sop to Judas.

Leaven was strictly forbidden from the home during the weeklong festival in homage to an exodus from Egypt so hurried that it precluded the Children of Israel from leavening their dough. So it would have been with pieces of unleavened flat bread that Jesus and the others attacked a mound of sweet, dried-fruit compote (harosset) symbolic of the mortar plied by enslaved Hebrew masons.

The disciples may not have fully understood at the time how Christs institution of the Eucharist to a traditional Hebrew celebration had radically transformed it into one like no other in history. By associating the consecrated unleavened bread and red wine with His body and blood, He created transcendent symbolism for all future generations of Christians.

Insight into the ritual foods served on the feast of Passover lead me to a more fundamental question: What constituted the diet of the ancient Hebrews and early Christians?

My search for an answer began in the Bible. I reviewed the dietary laws in the Books of Leviticus (11:1-47) and Deuteronomy (14:3-21), intended to set Gods chosen people apart from their gentile contemporaries. The laws categorized foods as either clean or unclean. Among the latter were pork, rabbit, camel, birds of prey, most insects (with the exception of locusts) and any fish that hath no fins nor scales, such as catfish, eel and shellfish. The Israelites bitter enemies, the Philistines, ate some of the proscribed foods, notably pork. This, as well as economic factors, may have engendered its prohibition. Mosaic law also forbade the cooking of kid in its mothers milk, which was a Canaanite ritual and therefore considered pagan. The gentile population of the Holy Land, and probably a small number of secular Jews, did not follow the Mosaic dietary code. Jesus and His disciples, however, as religious Jews, must have observed the precepts, at least during Christs lifetime. We can infer as much from the disciples shocked reaction to news of Peters meal with Cornelius in Caesarea (Acts 11:2-3). Popular conceptual attitudes concerning clean and unclean foods were about to change for the followers of Jesus. New Testament passages (Mark 7:15, Acts of the Apostles 11:5-9, Romans 14:20-23 and 1 Corinthians 10:25-26) would effectively nullify the Old Testaments dietary regulations.

Peters supper with the gentiles in Caesarea was more than just the communal partaking of food. The convivial meal confirmed the conversion of Cornelius. It had long been customary for Hebrews to seal almost every pact with a meal, whether secular or religious, beginning with Moses and the elders of Israel accepting Gods covenant (Exodus 24:8-11). Breaking bread established a sacred bond between them and their God.

Next page

![Claudia Roden - Claudia Rodens Mediterranean: Treasured Recipes from a Lifetime of Travel [A Cookbook]](/uploads/posts/book/289768/thumbs/claudia-roden-claudia-roden-s-mediterranean.jpg)