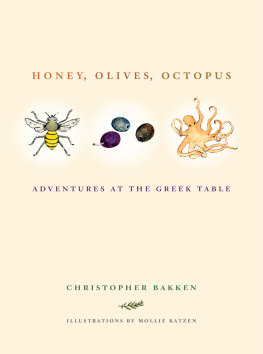

Honey, Olives, Octopus

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous support of

the General Endowment Fund of the University of California

Press Foundation.

Honey, Olives, Octopus

Adventures at the Greek Table

CHRISTOPHER BAKKEN

Illustrations by Mollie Katzen

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

BerkeleyLos AngelesLondon

University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu.

University of California Press

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

2013 by The Regents of the University of California

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bakken, Christopher.

Honey, olives, octopus : adventures at the Greek table / Christopher Bakken.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-520-27509-6 (cloth, alk. paper)

eISBN: 978-0-520-95446-5

1. Cooking, Greek. 2. Bakken, Christopher. 3. SubjectSocial life and customs. I. Title.

TX723.5.G8B28 2013

641.59495dc232012026481

Manufactured in the United States of America

22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In keeping with its commitment to support environmentally responsible and sustainable printing practices, UC Press has printed this book on Natures Book, which contains 30% post-consumer waste and meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.48-1992 (R 1997) ( Permanence of Paper ).

For my mother ,

Karen Seibel

In the afternoon heat I pick olives,

The leaves the loveliest of greens:

I'm light from head to toe.

Nazim Hikmet

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I owe sincere thanks to those cooks, artisans, restaurateurs, wine folk, agriculturalists, and friends who entertained my questions and invited me to their kitchens and farms: Eva and Stamatis Kouzis, Karolin Giritlioglu, Kyria Konstandina of Dalabelos Estate, Vasilis Petrodaskalakis, Eleftheria Pelekanaki, Pelayia Konsolaki, Nikos Bernikos, Yorgos Babounis, George Atsalinos, Aris and Maria Monovasios, Rita and Yorgos Paraskevopoulou, Dimitris Yerondalis, Markus Stoltz, Yannis and Chris Fekos, Maria Mavrianou, Michalis Makellos, Dimitris Triantafilopoulos, Michalis and Katarina Protopsaltis, Yannis, Maria, and Athanasia Protopsaltis, and Eleni Petrocheilou. Special thanks to Dimitris, Christina, Spyros, and Nikolas Panteleimonitis.

I am grateful to those who offered advice, enthusiasm, and research assistance: Titos and Renna Patrikios, John Psaropoulos and A. E. Stallings, Michael and Kay Bash, David Mason, Leon Saltiel, Jeremiah Chamberlin, David Yoder, Aliki Barnstone, Adrianne Kalfopoulou, Christian Nicolaides, Elaina Mercatoris, Allison Wilkins, Herbert Leibowitz, Willard Spiegelman, Tamar Adler, Scott Cairns and Marcia Vanderlip, Carolyn Forch, Pam Houston, Greg Glazner, and the team at Regal Literary, especially Michael Strong and Markus Hoffman.

The book couldn't have been written without support for research and travel provided by Allegheny College.

Parts of this book have appeared, in somewhat different form, in the following publications: Parnassus: Poetry in Review, The Southwest Review, and Odyssey: The World of Greece.

Roula Konsolaki, Natalie Bakopoulos, and Joanna Eleftheriou offered helpful comments on the manuscript. For her drawings, I thank Mollie Katzen. For his editorial brilliance and generosity, I am indebted to Ben Downing, il miglior fabbro. Thank you, Corey Marks and Darrin Pochan, for your appetites (and thank you for not drowning). Oscar, Karen, and Heidi Seibel: thank you for cheering my wanderlust. Thanks to my brother, Aaron Bakken, for picking olives alongside me. Thanks to my Greek brothers, George Kaltsas and Tasos Kouzis.

And, finally, thanks to my wife, Kerry, and my children, Sophia and Alexander, who sent me off to Greece with their blessings and welcomed me back home with love.

PROLOGUE

I had just arrived in Thessaloniki and was hungry. The college promised me a nifty apartment on campus, but it was still being painted. In the meantime, I'd be sleeping in a storage room in the basement of the gymnasium, where a rudimentary cot and a reading table had been installed. There was nothing in the refrigerator. Everyone else had gone to the beach for the weekend, so it was up to George Kassiopides, director of physical education, to orient me. Like Jack LaLanne, the exercise guru who had kangarooed through the television commercials of my childhood, Kassiopides was a wasp-waisted calisthenic addict with an inflated chest. He had a big, round, craggy face, atop which a merry mess of blonde curls was splattered, and he sped around campus on a coughing moped, elbows and knees akimbo, tornadoes of pine needles spinning in his wake. Kassiopides knew everything when it came to action and adventure, and it was he who taught me to hunt for octopus later that first year in Greece. I still find ingenious his trick of diving with an old pair of panty hose (nothing else seems to contain a just-harpooned octopus quite as well). But he didn't have much to say about where I should eat on a sleepy Sunday afternoon.

Take the bus into town and maybe you'll find something, he told me.

So I wound up in a sorry little taverna across from the bus stop in the suburb of Harilaou. Seated at a corner table, where I thought I'd be less conspicuous, I tried to decipher the menu with my pocket dictionary. The Greek language grates like the anchor chain, V. S. Naipaul says, and until I learned six or eight phrases on the soccer field (most of them obscene), Greek was indeed a clattering gibberish to me. I couldn't tell where individual words started and ended. Where did one even place the accents in Thessaloniki, this city of a million inhabitants where I'd be teaching literature for the next two years?

When the waiter came around, I pointed at three arbitrary items on the menu. It was not a spectacular meal, in hindsight, but it offered a foretaste of the hundreds of exquisite meals I'd have in Greece over the next two decades. First came chtipiti, a fiery mash of feta and hot peppers; then pikantiki, a salad of raw cabbage, carrot, parsley, and green onions; and last, a tin platter bearing a leg of octopus, still hissing from the grill. What remained on my plate when I finished eatingan acrid puddle of vinegar and oil, a curlicue of charred tentacle, a nubbin of bread, and a morsel of cheesewas evidence that I had made contact with the flavor of Greece. And I wanted more. I still do, twenty years later.

Since that day, almost everything I have learned about Greece I have learned at the table. The country's history is written in the elements of its cuisine: olives, bread, fish, and cheese. Meat, beans, wine, and honey. But the future is closing in. McDonalds and Kentucky Fried Chicken have arrived. The Greek economy is collapsing. Both slow food and local food have existed in Greece for thousands of years, but the traditional ways are under threat as air-conditioned malls and big box stores replace outdoor markets in Greece's cities. Before it was too late, and before those who remembered were gone, I wanted to explore the foundations of the Greek table. To do that properly, I needed to honor what brings everything else together: conversation, friendship, and the leisurely ceremony of dining around which Hellenic culture has evolved for the past several thousand years.

Next page