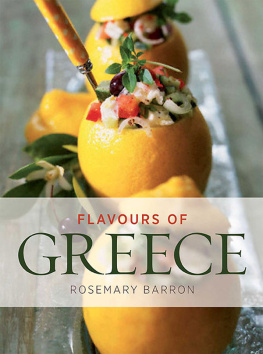

It is impossible for me to think of Greece without thinking of the colours, sights, aromas, and, above all, the flavours of Greek cooking. So many of my happy memories of the country are linked with food enjoyed in the company of good Greek friends or of new food experiences associated with out-of-the-way or exotically beautiful places high in the mountains, by the glistening blue Aegean Sea, or in medieval ports, picturesque villages, or the heart of cosmopolitan Athens.

Yet my interest in this fascinating, many-layered, cuisine began by accident: On an archaeological dig on Crete, cut off by rugged mountain passes from all but the most durable of supplies, my fellow diggers and I found ourselves eating the same foods our subjects had enjoyed some 4,000 years earlier. This was the beginning of a passionate and lifelong curiosity about Greek food and its history, and its place in our own culinary culture.

Fifteen years after this first prophetic encounter, I was back on Crete, this time to set up a cooking school. Kandra Kitchen was based in an old house which, 450 years earlier, had been rebuilt with stone rescued from a ruined monastery. Its wood-burning oven still worked, the huge wine press remained intact, remnants of once-elegant antique columns supported the steps, and the flagstone floor was gloriously shiny and worn. Kandra Kitchens programme ensured that each student enjoyed Greek foods, wines, and culture within the daily, seasonal, and festive rhythms of village life. I did, however, make one contribution to this otherwise idyllic state of affairs I installed a state-of-the-art kitchen, at that time the only one on Crete, to provide the classroom for testing and experimenting with Cretan foods and dishes.

Kandra Kitchen attracted enormous interest, in the United States (where I was living at the time) and Canada in particular, and the six years I ran the school on Crete and on Santorini (Cyclades) were very happy ones for me.

The constraints of family life, although perfectly enjoyable in their own way, prevented further long-term travel, so I turned to writing, teaching and lecturing on Greek foods and culinary culture, past and present. My itchy-feet were reasonably well-taken care of though, as these new activities entailed plenty of travel to the United States and Greece, to Canada, Australia, France, Argentina, Thailand and elsewhere. During this time, I wrote Flavours of Greece.

I hope my recipes here will pay some tribute to the wonderful spirit of friendliness that has engulfed me, and warms any visitor in Greece; that they will revive happy memories in those who have already travelled to Greece or her islands and in the Greeks who now live abroad.

As a visitor to Greece I was automatically awarded the status of a xsenos, which means a stranger-friend; with this comes, for any traveller, the protection of the gods and a magnificent welcome to match. Such a welcome always includes the sharing of food. You are not just given food by Greeks but asked to share with them the food they enjoy (somehow there is always enough!). In few other countries are food and its traditions so much part of the fabric of life, playing an important role in the rituals associated with birth and death and everything in between.

Of course, just because a recipe is ancient, there is no guarantee that it will taste wonderful. But, with Greek food, much of it does. When I open a recipe book I often recall that the first recorded collection of recipes dates from the days of ancient Greece, that Greeks established the first schools for chefs, and that a fastidious Greek gourmet invented the fork. And each time I hear the issues of the day discussed over dinner, my mind is drawn back to the scholarly dinners of antiquity when food, philosophy and conversation were considered inseparable companions.

My hope is that some of this enthusiasm for Greek food and culinary history will inspire my readers to discover more about both. Perhaps too it will persuade others to visit that beautiful and hospitable country and experience the delights of Greek food for themselves.

Rosemary Barron

Those who know Greece, even if only from a brief acquaintance, are aware that there is a vigorous culinary tradition in the country, with a distinct identity and character. There is a robust regional and local cuisine and an informed and lively interest in food and flavour. All these aspects are linked, in an amazing continuity of tradition, with the ancient world of over two thousand years ago.

Ancient Greece is universally accepted as the cradle of Western civilization, with its highly developed political and social system and rich intellectual and cultural life. In such a civilization could it have been possible that food and its preparation would not have been taken seriously? A remote possibility indeed. In fact, the ancient Greeks regarded cooking as both an art and a science and throughout the ancient world Greek chefs were accorded the status and reputation that French chefs now enjoy. The principles and practice of fine cooking and gastronomy as we know them today were first established in the abundantly stocked and highly creative kitchens of ancient Greece, and modern Greeks still enjoy the foods and tastes that inspired the chefs of antiquity.

What makes the style and flavour of Greek food essentially different from that of other Mediterranean countries? To discover that we need to take a brief look at the countrys history, since Greek cooking is greatly influenced by the twists and turns of its turbulent past.

Until around 3500 BC the early inhabitants of Greece grilled the food they had gathered, hunted, and fished over wood fires, baked it in glowing embers, or, like their Etruscan neighbours, cooked it in clay ovens. But with the advent of what has been called the Greek miracle the budding of the sophisticated Minoan civilization on the islands of Crete and Santorini Greek cuisine began to develop a strongly individual style.

At the height of its influence (around 1700 to 1400 BC) the Minoan state dominated the Aegean, and its culture spread throughout the Mediterranean. Trade links with North Africa brought dates and onions to the islands and forests were cleared to make way for widespread planting of vines and olives. Then, as now, Crete was a true Garden of Eden, producing some of the richest honey and sweetest fruits to be found anywhere, so it is no coincidence that the first sweetmeats were made in Minoan kitchens. The well-known Mediterranean sweetmeat