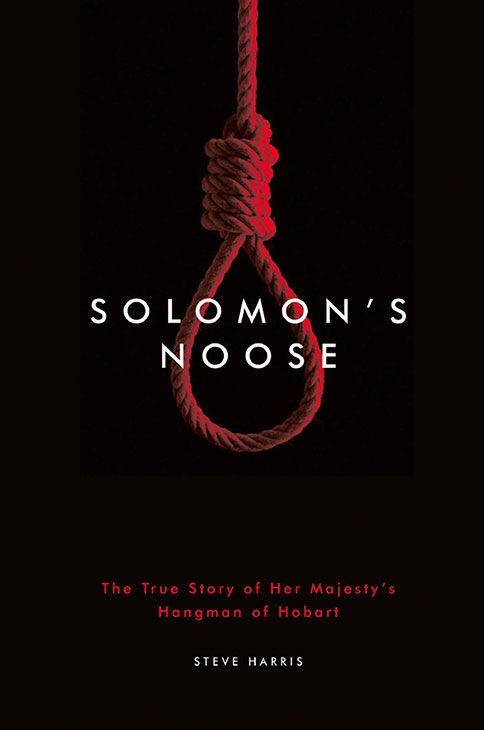

The Author

and Sources

S teve Harris is a fourth-generation Tasmanian. Recent research into his own family history, which includes convicts, policemen and settlers, re-ignited a broad interest in aspects of Australias national story largely forgotten or untold.

He has long been engaged with words and outcomes as publisher and editor-in-chief of The Age ; editor-in-chief of the Herald and Weekly Times ; founding editor of The Sunday Age ; founder of Melbourne Magazine ; CEO of Melbourne Football Club; and founding director of the Centre for Leadership and Public Interest at Swinburne University. He is a John S. Knight Fellow at Stanford University, a life member of the Melbourne Press Club, and was awarded an Australian Centenary Medal in 2001 for services to the profession and community. This is his first book.

The past is never dead. Its not even past.

William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun , 1950

Published by Melbourne Books

Level 9, 100 Collins Street,

Melbourne, VIC 3000

Australia

www.melbournebooks.com.au

Copyright Steve Harris 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers.

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Creator: Steve Harris

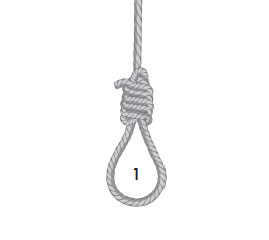

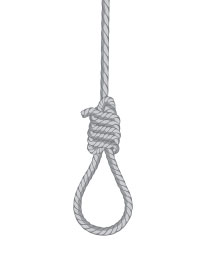

Title: Solomons Noose: The True Story of

Her Majestys Hangman of Hobart

ISBN: 9781922129833 (paperback)

Notes: Includes bibliographical references.

Subjects: Blay, Solomon, 1810-1894.

Executions and executioners--Tasmania.

Tasmania--Social life and customs--1803-1900.

Tasmania--Social conditions--1803-1900.

Tasmania--History--1803-1900.

Dewey Number: 364.6609946

Digital edition distributed by

Port Campbell Press

www.portcampbellpress.com.au

eBook Conversion by

S o l o m o n s

N o o s e

The True Story of Her Majestys

Hangman of Hobart

STEVE HARRIS

M

MELBOURNE BOOKS

Dedicated to family past and present.

Contents

Introduction

O f all the faraway places of the British Empire of the 19th century, nowhere was further than Van Diemens Land. This was where the Empire banished its unwanted, as far away as possible, out of sight across the horizon to an isolated island at the very bottom of all the maps of the known world.

Seventy thousand men and women, many of whom had barely ventured outside their own village or town, were despatched across 20,000 kilometres of seas they had never seen to an island Bastille with walls of wilderness and wild southern oceans, its arrowhead shape seeming to point ominously towards even deeper unknowns. It was a land first discovered in honourable deeds of exploration, but its identity quickly became one of damnation as the mightiest empires adopted hell on earth.

The home of a peaceful indigenous civilisation for thousands of years became a hellish prison colony for an advanced civilisations human waste, those thousands who had challenged or transgressed an empires authority and law in England, Ireland, Scotland, Africa, America, Canada, West Indies, Italy and even Iceland. Survival and wellbeing would depend on the personal choices of those in positions of, or subject to, authority. The former could arbitrarily decide whether to free or gaol, forgive or punish, save or hang; the latter could individually resolve whether to obey or challenge the law, endure or resist punishment, accept or escape.

There was often little differentiation between those clothed in bewigged finery and red army uniforms and those in rough convict cloth, whether their days were spent amid polished wood and chandeliers, or irons and stone cells. The line of authority did not always differentiate between those who were just, civil, fair, learned, honourable or progressive, and those who were despotic, cruel, illiterate, greedy, drunk, incorrigible and inhumane.

But all of their lives, one way or another, were defined and connected by a vice-regal stamp, judicial gavel, bureaucratic quill, whip, manacle, cell-key and gallows.

Remarkably, in the swirl of damnation and despair there were among the exiled, and those watching from afar or drawn to visit, seeds of ideas, theories and beliefs about law and order, punishment, democracy, religion, education, medicine, welfare, womens rights, race, sexuality, biology, and the environment. Designed as a dumping ground at the end of the earth, the penal island drew the fertile minds of Charles Darwin, Anthony Trollope, Charles Dickens, Mark Twain, William Booth and James Backhouse, as well as various kings, princes and bishops. These were people intellectually engaged, one way or another, in the contest between Paradise and Hell, the hand of God and Man, the balance of hope and hopelessness.

But for tens of thousands of banished individuals, theirs was a more personal, more life and death interest. The challenges of survival were common, but of all the 70,000 convicts sent to Van Diemens Land, one mans choices made his story unique.

He was born Solomon Bleay, but became better known as Blay. He sought to overcome his impoverished childhood in England by stealing and making fake coin, and when he was caught he was banished to Van Diemens Land. His chains would be unshackled, and he would eventually become a free man by law, but by his own hand he was condemned to a life without true freedom or peace.

Blay chose to overcome his imperilled life in Van Diemens Land by making the fateful decision to deal in the currency of death. He chose to carry out the last sentence of the law as the final and ultimate hand of an empires judgement the man who would put a rope around the neck of men and women and hang them until they were dead.

Solomon Blay would be Her Majestys public executioner.

He became the embodiment of an empires iron fist in its most distant exile, the Empires youngest hangman, its longest serving executioner. He became its most feared man one who, some newspapers speculated, put to death more people than perhaps any other man in the world.

But his choice of escaping punishment by becoming a hangman was its own life sentence. Every time the bells tolled to foretell a hanging, they also tolled for Blay. Every time he dropped another soul into eternity, he retreated into his own cell of self, living with his own noose of personal demons and public damnation.

Blay was the last man to look into the eyes of more than 200 men and women, some as young as 16 and others as old as 76. He was the final witness to the struggle between law and order, good and evil, humankind and Mother Nature, hope and fear.

This is the story of Solomon Blay, a unique man in a unique time in a unique place: Van Diemens Land.

An Oxford Graduate

T he great town of Oxford offered rich lessons in life for young boys like Solomon Blay, with its trinity of university (the oldest in the English-speaking world), church (established in the 1500s) and castle (dating back to William the Conqueror).

But Solomons lessons didnt come from educated men, in what had been a universitas since 1232 under the patronage of kings and popes. Its motto dominus illuminatio mea , the Lord is my light, meant nothing to him. The earnest prayers and hymns in Christ Church, where King Charles I lived during the English Civil War, werent for his ears.