PENGUIN PRESS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2022 by Edward Enninful

Penguin Random House supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for every reader.

constitutes an extension of this copyright page

ISBN 9780593299487 (hardcover)

ISBN 9780593299494 (ebook)

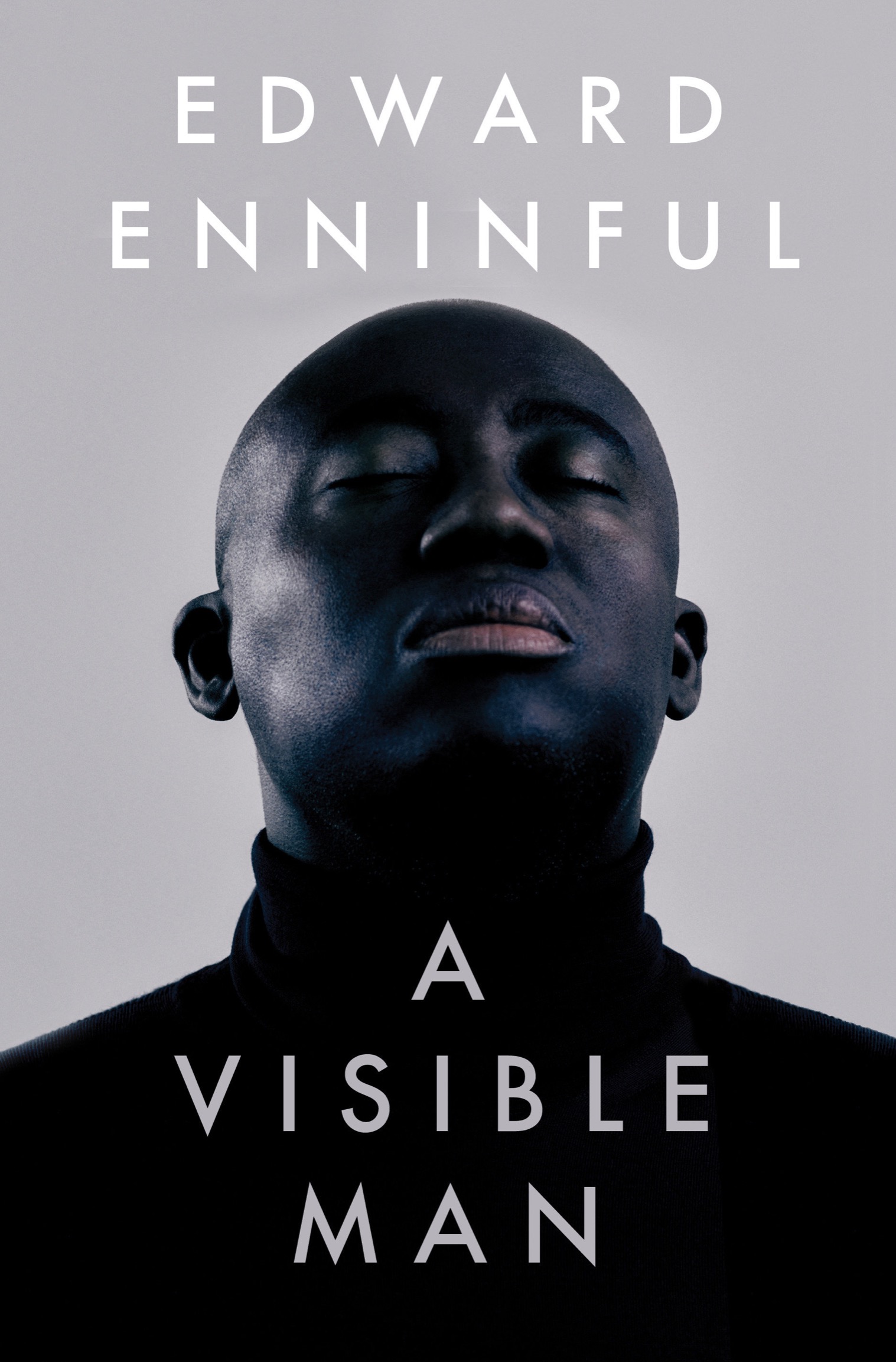

Cover design: David Mann

Cover photograph: Rafael Pavarotti

Typeset and designed by Office of Craig, adapted for ebook by Estelle Malmed

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

pid_prh_6.0_140851407_c0_r0

For my mother, Grace

CONTENTS

PREFACE

One morning, during the early summer weeks of 2020, a time when London was eerily still and, even more strangely, sunny, I was in Hyde Park taking my Boston Terrier, Ru, on a socially distanced walk with a friend.

I was fired up. A pandemic was ripping through the world, bringing with it tragedy to countless people, and it seemed clear that societies across the globe were coming apart at the seams. Then in late May, I sat glued to my phone in horror, watching as George Floyd was murdered in Minneapolis. In the aftermath, the streets across five continents were filled with protesters. The world tilted on its axis as the most significant social justice movement in decades met the worst international health crisis in a century. I felt a familiar gnawing sensation within myself and shared with my friend that, after having been approached many times to write my memoirs, Id finally agreed to do it. The world had stopped. Then it had exploded. It was time. It was also time for me, personally. Id got to the point in my 34-year-long career where I could take stock of both my failures and my victories, and view them against the backdrop of a world Id helped to change too, in my own way.

My friend, who, like me, grew up in an African household in the heart of London and had found great success in his own career, asked me what the book would be about. Oh, you know, I sighed, a boy from Ghana making his way in a racist, classist industry, and the struggles along the way.

He stopped me. Ed... nah, my brother. You move with leaders and tastemakers; youre surrounded by the most powerful, amazing women. We see glamour and swagger; we dont see a struggling Black person. Make sure you give us power and success. We need that.

I was surprised by his perception. Like most immigrants like most Black people, in fact I didnt feel like I had made it. Do you ever? Success for us is fragile, a fact that we have sadly come to appreciate more than most in the last few tumultuous and traumatic years.

The only thing I could say with any certainty about my life was that it had been driven by an all-consuming addiction to forward motion, and it still is. I had worked day into night in the fashion industry since I was sixteen, first modelling, then researching and hauling and steaming and putting in longer hours than were healthy. And I had certainly made an emotional investment in this calling that was not always fabulous for my mental health, either. Fashion shows, shoots, rejections, aggressions (both macro- and micro-), overnight flights and going straight to the studio, fittings, consultancies, making deadlines in the face of health and relationship and family sacrifices. I overachieved where others rested, ignored weekends, rarely took holidays and replied to every email I received straight away. (This last habit is one I picked up from Anna Wintour, incidentally.) It may all look glamorous from a distance and yes, it has been filled with joys but it has also felt like a ceaseless struggle.

So it took me a moment to see it from my friends point of view, which was not what I had come through, but where I had arrived at. Like me, this friend came from a place where his success was unlikely, the exception to the rule. He knew how important it was to provide models of joy and success for kids like us. But he hadnt lived my journey, and certainly didnt know all its contours, so he didnt yet fully understand why everything Id experienced in my life was so critical to where I eventually ended up.

The question I am most often asked, especially by younger people, is: How did you do it? At such a powerful crossroads of change, it felt like the right time to bring the answers even if, to be perfectly honest, I never saw myself as the type to write a memoir. By nature, I am rarely nostalgic. When, fresh from the printers, a new edition of British Vogue is placed on my desk each month, I dont spend much time dwelling over it, and certainly no time congratulating myself. Why look back when you can look forward? Why look in when you can look out? Wheres the next evolution? I throw everything into my work, but once its done, Im really more concerned with whats new. The future is my thing.

It is this same energy that has propelled me through my life. Im thankful for it. I didnt get to where I am born on a military base in Ghana, where I spent my childhood, to the position of European editorial director of Vogue and editor-in-chief of British Vogue by being unduly fascinated with myself. I embrace whats ahead, both by instinct and choice. Someone has to drag us into the future, I figured. I always wanted to be a part of that.

So it was that I found myself in Hyde Park that morning, chewing over the nature of the world and the story I wanted to tell in this book. The friend happened to be Idris Elba, the same dear friend who held my hand a year or so later while I cried tears of joy at my wedding, waiting for the minister to declare me married to Alec, my partner of more than twenty years, and now my beloved husband. We were in The Orangery of Longleat House in Wiltshire on a late winters night, loaned to us by my friend Emma Thynn, Britains first Black Marchioness, and her husband Ceawlin, the eighth Marquess of Bath. Our families were there, and dearest friends too. Everyone was beautifully dressed. White flowers heaved on the trellis, the grounds outside were lit by torches; the room was full of love. When the minister asked if anyone present knew of any reason why Alec and I couldnt be joined in matrimony, Rihanna, who was running late, burst through the back doors in a black lace dress, her pregnant belly resplendent. Through the tears, everyone burst into peals of laughter. Classic Rih.

I looked around the room that day at all those friends and family who had supported me throughout my life and saw my world in full focus. There were friends from fashion, Hollywood and beyond, but also many wonderful activists I had come to know and work alongside, the designers who had changed the way they do business, the editors and writers who had helped to lay the foundations for a new world in fashion that we built together.