M Evans

An imprint of Rowman & Littlefield

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200

Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

10 Thornbury Road, Plymouth PL6 7PP

United Kingdom

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

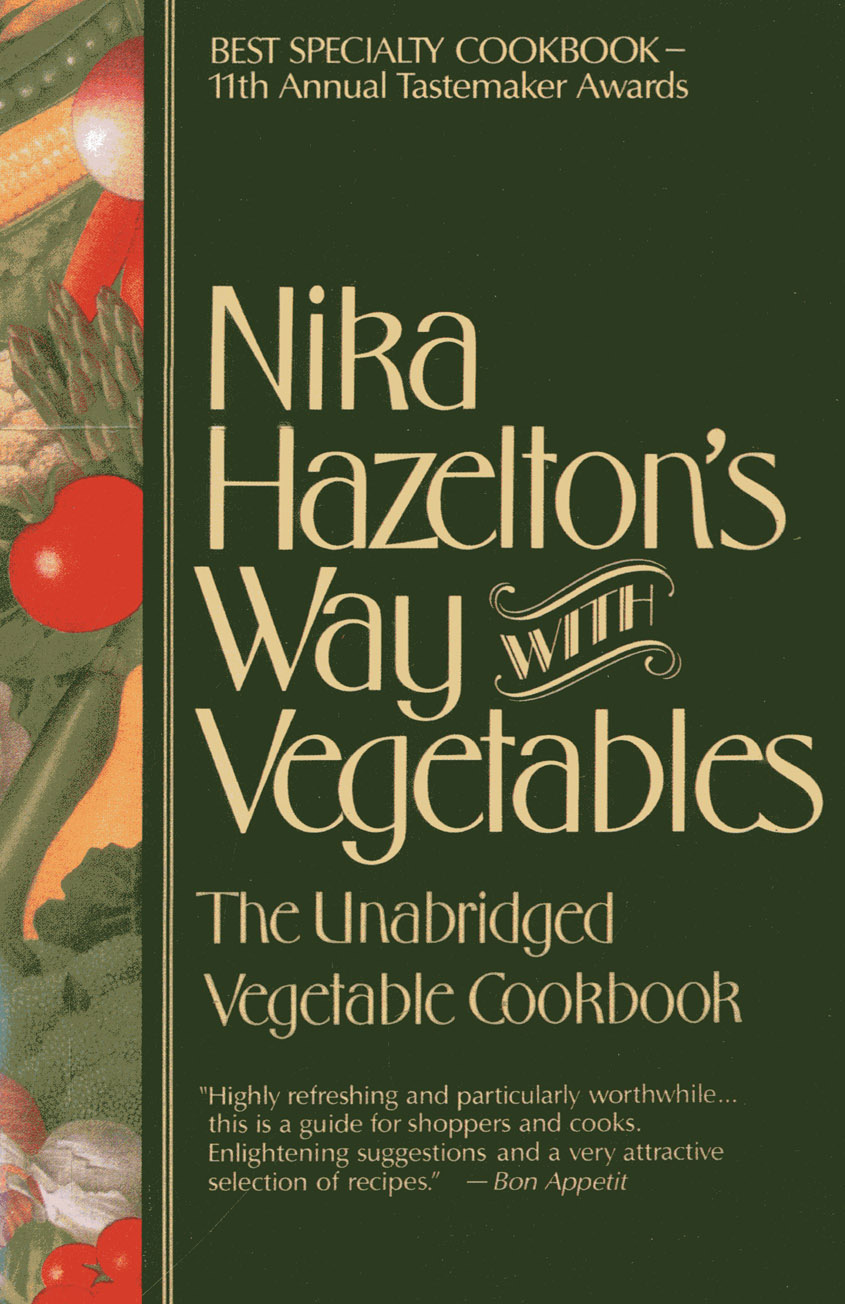

Hazelton, Nika Standen.

The unabridged vegetable cookbook.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. Cookery (Vegetables) 2. Vegetables.

I. Title.

TX801.H37 641.5636 76-23451

ISBN 978-1-59077-270-6

Copyright 1976 by Nika Hazelton

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the written permission of the publisher.

M. Evans and Company, Inc.

216 East 49 Street

New York, New York 10017

Design by Joel Schick

Manufactured in the United States of America

Distributed by N ATIONAL B OOK N ETWORK

For my son, Julian

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My special thanks go to two people who have helped me greatly with this book: Martha Durham, a researcher, and R. A. Seelig, of the United Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Association of Washington, D.C.

I am also indebted to Messrs. Theodore Torrey, Manager of Vegetable Research, W. Atlee Burpee Co.; Pete Bonucci, Garden Seed Coordinator at Northrup, King & Co.; Dr. Alan Stoner, Research Horticulturist for USDA, Vegetable Laboratory of the Agricultural Research Center; and to Derek Fell, Director of the National Garden Bureau and Director of All-America Selections.

Preface

This book is about fresh vegetables, their history, nutrition, and ways of keeping and preparing them. Any plant eaten as a vegetable rather than as a fruit has been included, regardless of its botanical classification. For instance, the tomato is a fruit, which we eat as a vegetable, whereas rhubarb is a vegetable we eat as a fruit. I have only discussed vegetables that are available in the United States, omitting many tropical, exotic and rare vegetables which would be hard to find in our country.

As in all but standard cookbooks, the recipes reflect my personal preferences. I have tried not to repeat the excellent, basic recipes found in standard cookbooks. I have chosen dishes which feature a specific vegetable, rather than the many soups, stews and casseroles in which vegetables play a secondary part. I have omitted recipes that struck me as uncommonly exotic, such as some Latin American, African and Oriental dishes.

My basic usage instructions reflect my own experiences: I think vegetables should be eaten as fresh as possible, and I consider over-cooking the death of almost any vegetable. I also think that, in general, vegetables should be cooked simply to let their own flavor dominate without confusing it with too many herbs, seasonings and other ingredients. Vegetable cookery is mostly a matter of timing; and the successful cook tends to rely on judgment rather than careful measurement.

The nutritional statements and caloric figures are based upon the definitive source on the subject, Composition of Foods, Hand Book No. 8, Agricultural Research Service of the United States Department of Agriculture. The caloric values are based upon 100 grams, which translates to about 3 ounces. This amount is close enough to 4 ounces, or cup (liquid) measure, an average vegetable helping. Generally speaking, there is little difference in the number of calories in cooked, unseasoned vegetables whether fresh, canned or frozen.

Finally, I may add that this book is based upon a lifetime preference for vegetables over other foods.

Footnote

Sources used for botanical information include Websters Second International Dictionary and Websters Third New International Dictionary.

Vegetables Then and Now

Primitive man initially gathered the edible parts of wild plants for food, an interesting and admirable effort, though not quite as brave as trying the first oyster or lobster. From this first step, the realization followed that the seeds of some food plants, notably the grasses, could be sown, harvested and stored. Wheat and barley, two of our oldest crops, were apparently cultivated in the Middle East between 8000 and 5000 BC, and rice was a staple crop in China as early as 2800 BC. Whether this early crop cultivation occurred by accident or purpose we cannot know, but we do know that it was the essential step towards civilization. Agriculture enabled man to develop a settled, stable way of life without which civilization could not have developed.

Mans transition from food-collector to food-cultivator was a slow one, taking thousands of years during which many plants evolved from their original wild state. It is difficult to retrace the paths of evolution: by natural variation, human selection of seeds, and natural or man-made hybridization, many food plants have changed considerably. This especially holds true for the cucumber, onion, sweet corn, white and sweet potato and squash, to mention a few, whose wild ancestors are impossible to identify.

The presence of a wide variety of food plants in different parts of the world is largely due to the activities of man. In very early times, these plants traveled to parts of the world that were easily reached by land. Later the seafaring and empire-building nations of antiquity, such as the Phoenicians, the Persians, the Romans and the Arabs, introduced their native food plants to places that were not familiar with them.

The great, all-important interchange of crops took place after 1492, when Columbus, returning from his first voyage, took back to Spain the first corn ever to reach Europe, and on his second voyage, brought European seeds back to America. Among the crops introduced to America from the Old World were citrus, sugar cane and rice, as well as all the European crops familiar to the settlers of the temperate zones. But the exchange of food plants was not limited to America and Europe. The ships of the slave traders, along with their infamous cargoes, brought to America the food crops of West Africa such as yams and pigeon peas, and brought back to Africa American crops such as corn and cassava. Within a short time, these New World plants were being widely cultivated in Africa, supplementing the limited crops native to the regions south of the Sahara. Other trading between continents brought bananas and rice to Africa via Portuguese ships coming from Asia; chiles from America were brought to Asia and enabled the Indians to make hotter curries. In Australia, food crops date back to the first European settlements at the end of the 18th century, since the native aborigines did not cultivate plants. Coffee, which originated in Ethiopia, traveled first from Mocha and then Java to Latin America where it became a primary cash crop, and pineapple, from Brazil, became equally important to Hawaii and some Caribbean islands.

It is unfortunately beyond the scope of this book to treat the history of food plants more fully than it is in the following pages. Suffice it to say that the improvement of food plants is by no means a new practice. Seed selection was a fine art in the 18th century, and the emergence of the science of genetics in the 19th century enabled plant breeders to select suitable parent plants, or hybridize them or produce new genetic variations by treating plants with chemicals or even x-rays. The sight of plants treated with controlled radiation, which I saw years ago at the atomic labs in Brookhaven, was bizarre. Yet experiments in radiation genetics by the Atomic Energy Commission have also produced rust-resistant oats and peanuts with a 30 per cent higher yield. And science did double the yield of many crops during the last century, as well as improving greatly on their quality.