Group portrait from the Camp Weld Council. Seated in middle row, left to right: White Antelope, Bull Bear, Black Kettle, Neva and No-ta-nee. Kneeling in front, left to right: Wynkoop and Soule. Interpreter John Smith is standing in back, third from left. Denver Public Library, Western History Collection, call number X-32079.

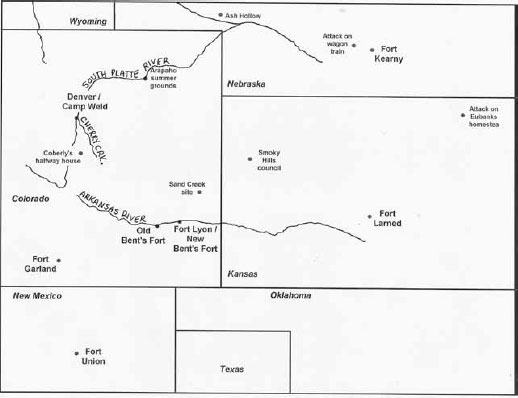

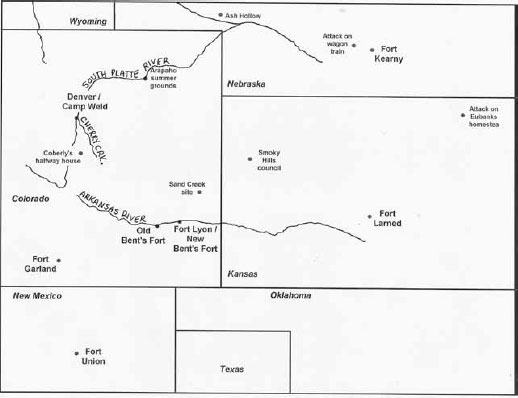

The Cheyennes and Arapahos roamed the high plains east of the Rockies, primarily in Colorado, Kansas and Nebraska.

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2010 by Carol Turner

All rights reserved

Cover images: The painting was produced by Lynn Turner, and all other images are courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

First published 2010

e-book edition 2012

ISBN 978.1.59629.943.6

Turner, C. A. (Carol A.)

The forgotten heroes and villains of Sand Creek / Carol Turner.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

print edition ISBN 978-1-59629-943-6

1. Sand Creek Massacre, Colo., 1864. I. Title.

E83.863.T87 2010

973.737--dc22

2010015719

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For John and Lynn, with love.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many thanks to Byron Strom, descendant of Silas Soules brother, William Soule, and keeper of the Soule flame. Byrons generosity of spirit is inspiring. Thanks also to Vicki Casteel, who shared her many historical documents and thoughtful insights with me about the characters involved in this drama. I owe Vicki particular thanks for tracking down the grave of Joseph Cramer. I also owe many thanks to Barbara Gay, Dana Younger (a distant cousin of Samuel Tappan), Sharon Crowder, Garry OHara at Riverside Cemetery, Molly McGarry, Criss Clinton (aka Jim-Criss), Richard Turner, Lynn Turner and John Turner.

INTRODUCTION

During the years of the Civil War, Colorado was embroiled in its own battle: the struggle between the increasing waves of white settlers and the tribes who lived in the region. Both sides were deeply divided within themselvessome worked tirelessly to find a way to coexist peacefully; others wanted total war. At a moment when the peacemakers thought they had found a way forward, those who preferred the violent solution intervened.

These are the stories of fourteen people whose lives intersected over the most infamous event in Colorado history: the massacre of Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians at Sand Creek.

CHIEF LEFT HAND

Gifted in languages and marked by a rich curiosity about the white world, Left Hand was a man ahead of his time. He possessed a clarity of foresight that few around him shared and an unrelenting pragmatism that informed every action he took. Long before others realized the truth, Left Hand understood that there was an endless supply of white settlers and that his small tribe would either adapt or face annihilation. Against all evidence to the contrary, he never gave up hope that it could be the former instead of the latter.

Born in a Southern Arapaho village in the 1820s, he grew up riding, hunting and raiding the traditional enemies of the Arapahos, such as the Utes. Called Niwot in the Arapaho tongue, he had a brother, Neva, and an older sister, MaHom, with whom he remained closely tied throughout his life.

Had it not been for MaHoms marriage to a white man, perhaps Left Hand might have lived a more typical life. As many around him did, he might have developed a hatred for the invaders and died on the plains, fighting to keep them out. But that was not his fate. As he entered adolescence, his teenage sister married a white trader who worked for William Bent, owner of Bents Fort. MaHoms husband, John Poisal, lived with the Arapahos and took an interest in his wifes two brothers. Poisal taught them both English. While Neva learned the basics, Left Hand became adept with the strange tongue. By mingling with their allied tribes on the plains, the Cheyennes and Sioux, he learned their languages as well. Throughout his life, he served as interpreter between these tribes and the whites.

Sometime in his twenties, Left Hand married, but his wifes name is unknown. Nothing is known about their children, and no pictures exist of Left Hand or his wife and children. One pioneer described Left Hand as the finest looking Indian I have ever seen. He was over six feet tall, of muscular build and much more intelligent than the average Indian. Left Hand became an Arapaho chief sometime during the 1850s, and his name began to appear in the newspapers and other documents of the day. Because of his language skills, he became a spokesman for the Arapahos.

The supposed first house in Denver, built by A.H. Barker near lodges of John Poisal and MaHom, sister of Left Hand, 1858. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

In 1863, the main Arapaho chief, Little Raven, refused to accompany a delegation to Washington, D.C., when they departed for the east before Left Hand could join them. Little Raven did not trust the interpreter John Smith, who had been accused of selling the tribes their own annuities and misrepresenting their statements.

Left Hands family became further connected with the whites when his niece, Margaret, the daughter of MaHom and John Poisal, married the respected Indian agent Thomas Fitzpatrick. Fitzpatrick was instrumental in organizing the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, which gave the Southern Arapaho and Cheyenne tribes legal rights to the territory between the South Platte and Arkansas Rivers.

The 1850s brought hard times to the Arapahos. The once abundant herds of buffalo and antelope grew more difficult to find as wagon trains and stagecoaches moved across the plains to California. The tribes became dependent on the government annuities promised in the Fort Laramie Treaty, but deliveries were sporadic. When the U.S. Senate decided that the terms were too generous and cut the annuities from fifty years to fifteen, the chiefs signed with barely a protest.

Starvation, cholera and smallpox took their toll during the decade, along with the devastating effects of whiskey. As early as 1834, the federal government had outlawed the sale of whiskey to Indians, but plenty of white traders still made good bargains, exchanging the stuff for buffalo hides and beaver pelts.

In 1858, the year the Pikes Peak gold rush began, Left Hand did something extraordinary. Determined to find out as much as he could about the white world, he packed his wife and children into a horse-drawn wagon and headed east into Nebraska and Iowa.

Next page