ENOUGH IS PLENTY

THE YEAR ON THE DINGLE PENINSULA

Felicity Hayes-McCoy

FIRST PUBLISHED IN PRINT FORMAT 2015 BY

The Collins Press

West Link Park

Doughcloyne

Wilton

Cork

Felicity Hayes-McCoy 2015

Photographs courtesy Felicity Hayes-McCoy and Wilf Judd, except for pp. 150 and 151, which are courtesy Isabel Bennett.

Felicity Hayes-McCoy has asserted her moral right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Irish Copyright and Related Rights Act 2000.

All rights reserved.

The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means, adapted, rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owners. Applications for permissions should be addressed to the publisher.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-84889-236-1

PDF eBook ISBN: 978-184889-889-9

EPUB eBook ISBN: 978-184889-890-5

mobi ISBN: 978-184889-891-2

Design and typesetting by Dennison Design

Cover design by Dennison Design

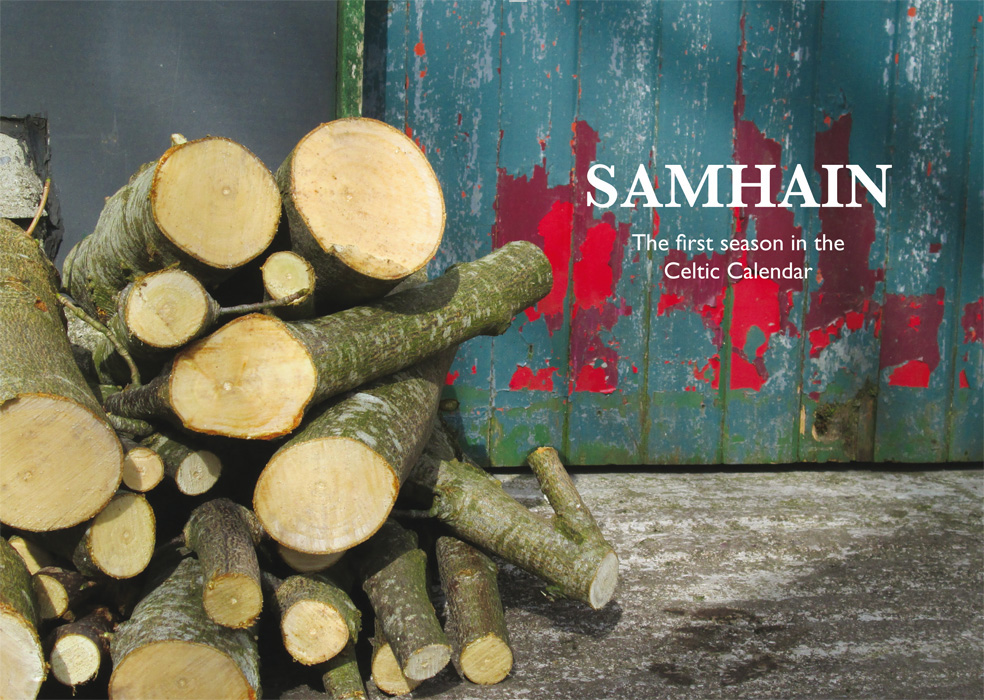

Cover photograph: roadside furze on the Dingle Peninsula

ENOUGH

IS PLENTY

THE YEAR ON THE DINGLE PENINSULA

FELICITY HAYES-MCCOY from Dublin has had a successful career as a writer, working in theatre, radio, television and digital media. She shares an interest in design, folklore and the Irish language with her husband, English opera director Wilf Judd. In 2002, they bought and restored a house in Corca Dhuibhne, Irelands Dingle peninsula. They now live and work there and in Bermondsey, London. Her published works include stories for children and her memoir, The House on an Irish Hillside.

For more information, visit www.felicityhayesmccoy.co.uk

You can also keep up to date at

You can also keep up to date at

https://www.facebook.com/fhayesmccoy

To Alice Judd who became Pat Fisher

When I finished Felicity Hayes-McCoys first book, The House on an Irish Hillside, I felt a sense of well-being. I had walked with her around the peninsula and experienced her wonder and delight. The book glowed with an appreciation of her lifestyle in Dingle.

When I began her second book, Enough is Plenty, I wondered if the magic would continue. It did! I was again immersed in her warm appreciation of this mystical place and delighted to revisit Nellies house and again meet Felicitys husband Wilf and good neighbour Jack. In her second book she has settled into life in Dingle and the fruits of her garden are finding their way on to her kitchen table. Wonderful pictures capture the wildness of the Dingle peninsula and recipes accompany the pictures of her home-grown produce. She digs deeper into the significance of ancient Celtic rituals and the traces of their influence on the present-day life in Dingle, lacing the old to the new.

This book is a celebration of all that is good and meaningful in Dingle, in Kerry and, indeed, in Ireland.

Alice Taylor

This is a book about ordinary things and small, bright pleasures that can easily go unnoticed.

Its a view of the year from a stone house on Irelands Dingle peninsula, a place where life is still marked and shaped by Irelands Celtic past. People who live here still use the Irish language in their everyday life. In Irish, the peninsula is called Corca Dhuibhne which is pronounced something like Korka Gweena. That name itself holds an ancient memory. It means the territory of the people of the Goddess Dan, a fertility goddess worshipped under many names in different lands across millennia.

For the ancient Celts, darkness, however bleak, barren or long drawn out, contains by its nature the dormant seeds of light. Its a belief reflected in the Celtic calendar which sees winter, not springtime, as the starting point of the year.

For thousands of years, the Celts celebrated the cycle of the seasons as a sign that the universe was in balance. In their world view, everything that lives must die to live again. So, for them, life and death held equally vital places in a repeated pattern, expressed by the seasons of the year. They saw the seasons as a reflection of eternity, endlessly turning from darkness to light and back again.

In this circular image of eternity each thing follows the next in its allotted sequence, like the notes of a tune or the steps in a dance. And because each thing has a vital place in the completed whole, all are equally important.

The Celtic seasons are called Samhain, Imbolc, Bealtaine and Lughnasa . On Irelands Dingle peninsula they still shape the cycle of the year.

The First Month of Samhain (Sah-win)

The ancient Celts saw darkness as a fertile state, full of dreams and possibilities. They also believed that turning points between one thing and another offer opportunities for heightened awareness and understanding. So, because November begins the darkest season of the year, the turning point between October and November is one of the most significant dates in their calendar. It begins the season of Samhain which begins the Celtic year.

For the Celts, each day began at sunset, not sunrise, and each new month started at sunset on the last day of the month that had gone before. The start of the season of Samhain was celebrated on 31 October, the night now known in English as Halloween, the Night of the Spirits.

It was believed that at Halloween the dead returned to the homes theyd once lived in on earth. Beloved ancestors were welcomed with fires and feasting, evil spirits were scared off by grotesquely masked dancers, and attempts were made to peer through the veil of time and see the future.

Im writing this in a stone house in the foothills of the last mountain on Irelands Dingle peninsula. Living here in a community that balances 21st-century life with a powerful sense of its ancient cultural inheritance, you can still see and feel the links between the changing seasons and the dynamic world view which shaped the rhythms and rituals of the Celtic calendar.

Next page

You can also keep up to date at

You can also keep up to date at