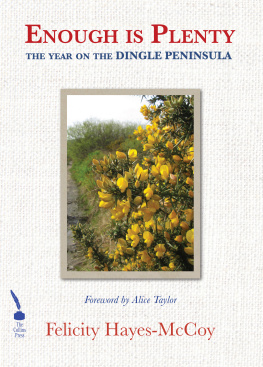

Felicity Hayes-McCoy from Dublin writes for radio, television, music theatre, print and digital media. She and her husband, the English opera director Wilf Judd, divide their life and work between a flat in inner-city London and a stone house in the west Kerry Gaeltacht. Her books include Enough Is Plenty The Year on the Dingle Peninsula (2015). The daughter of the late Irish historian G. A. Hayes-McCoy, she is a founding member of the UK Womens Equality party.

Twitter: @fhayesmccoy

In memory of

Mary (May) OConnor and Marion Stokes

THIS BOOK WOULD NOT HAVE BEEN WRITTEN had it not been for the hundreds of letters I received from my late mother, and the long hours we spent in conversation. While it is by no means a history, I owe an immense debt of gratitude to the historians, biographers, folklorists, poets, playwrights and political commentators whose works I have absorbed and returned to over a lifetime of reading and writing; and to the colleagues and friends, including the late Peter Fozzard of the BBC, who, over decades, have contributed to what remains an ongoing exploration of the nature of art and memory. Any errors I have made and conclusions I have drawn are, of course, my own.

My thanks are due to many individuals. In Galway, they include Librarian John Cox and Archivist Barry Houlihan at NUI Galways James Hardiman Library, where the G. A. Hayes-McCoy papers are held. In Dublin, Raghnall Floinn, Director of the National Museum of Ireland, provided information relating to my late fathers responsibilities there, and Dr Pauline OConnell, formerly of St Ultans Hospital and what is now the Coombe Women & Infants University Hospital, spoke and wrote to me about medical and social conditions during the early years of the Irish State. I owe particular thanks to Lucy Keavney of The Countess Markievicz School who gave me permission to use her tweets from the 2015 Hanna Sheehy Skeffington School. In Corca Dhuibhne I received constant help from Bernard MacBrdaigh and his colleagues in Dingle Library. I am also grateful to my Kerry neighbours, particularly the women who contextualised my knowledge and experience both of the place of women in rural Ireland and of the Irish language. In Enniscorthy, Katch Kavanagh was generous with her memories of Marion Stokes, and Maria Nolan of the Focal Literary Festival facilitated my initial talk in the town and subsequent visits there. I am also grateful to Jarlath Glynn, Enniscorthys Librarian, Grinne Doran, Wexfords County Archivist, and, of course, to the woman at Enniscorthy Castle who raised her hand and asked the question that originally sparked this work.

In the months when I was working on this book in the UK, I began each day with a pencil, paper and a cup of tea in the More London branch of Pret A Manger. Id like to thank all the friendly staff there for the cheerfulness and interest with which they kick-started my mornings.

My thanks are also due to my husband, my brothers, my brother-in-law Sen OLeary, and to numerous individuals who sent me memories and material, including Cormac Lawler and his mother Geraldine Lawler (ne Cunniffe). Finally, I am grateful to all at The Collins Press and, as ever, to my agent Gaia Banks at Sheil Land Associates.

Readers unfamiliar with the Irish language will find assistance in pronouncing the Irish words in this book on my Facebook author page.

Experience suggests that this book may produce further discussion of the issues it explores. I would be delighted if readers would like to share in my conversations on Twitter

THIS BOOK TELLS MANY STORIES. Some contradict each other. Some may not be true. All depend on angles of perception and on memory. Awareness depends on where you stand when you look at things, and many layers of emotional inclination and unconscious prejudice intervene when youre looking back. Individual, family and communal memory shape our sense of who we are and where we belong. So do imagination, aspiration and chance. So does the absence of memory.

I remember a night in Sinnotts pub on Dublins King St in the 1970s. It was drinking-up time, the door was bolted and Eugene was gathering glasses, washing up and asking if we had no homes to go to. At the end of the bar the actor Alan Devlin was getting obstreperous. Eventually Eugene, who had had a long night, told him to get out. There was a moment when it looked as if Alan was going to be difficult but a friend threw an arm round his shoulders and eased him out the door, and someone bolted it behind them. Moments later, someone else unbolted it again and Devlin sidled through the crowd and back onto his barstool. He was wearing a brown paper bag over his head. Eugene turned round, saw him and roared at him. Right, thats it, feck off out of it, Devlin; youre barred. Alan removed the bag from his head to reveal a look of wonderment. How, he asked, did you know who I was?

More than half my life has been spent as an Irish emigrant. I went across the water to England in my early twenties, married and built a career there. Yet as long as my mother continued to live in the family home in Dublin I never thought of myself as having emigrated. Throughout nearly forty years of living and working in London, despite the fact that I have had little or no contact with the Irish Diaspora there, my sense of identity has remained entirely Irish. Now, thanks to budget airlines and broadband, I divide life and work between an inner-city flat in London and a stone house at the end of Irelands Dingle Peninsula. But for the majority of my life my physical roots were in one country while my cultural and ancestral roots were in another. Even when Twickenham or Ealing or Finchley was home, I had an untroubled sense that home was some place else. Who I am appears to hinge on my being Irish.

My experience is not unique, either to me or to Irish people; often identification with the old country can persist through generations, though in many cases a return to it at such a remove would be disorientating and disillusioning. A sense of identity is a complex thing. It is shaped by subtle interfaces between individuals, family and community as much as by location, education, customs and traditions. It relies on the passing on of memories from one generation to another and the constant rearranging and reinterpreting of related and unrelated fragments of information, in repeated attempts to produce narratives that make sense. Wired into human consciousness is an instinctive need to pass on the stories that, by providing links to our ancestors, provide us with informed, healthy and enhanced perceptions of ourselves.

The story of this book began two years ago with a random question. I was in Enniscorthy, County Wexford, the home of my maternal grandmothers people for generations and a place I remember well from my childhood. I had been invited to speak at a literary festival, in a wide, elegant room on the first floor of the grey Norman castle that dominates the town. We were talking about shared memory when a woman in the audience raised her hand and asked a question. How do you know that what you remember is the truth? She was one of five siblings, she said, and we all shared the same experiences. We lived in the same house with the same people. But not one of us remembers anything in the same way. The book Id been talking about, called The House on an Irish Hillside, is a memoir, so I had been involved in many discussions about memory since I had written it. But this womans question provoked a particular response. Heads went up and body language changed. From my seat on the platform I could see people all round the room exchanging glances. Some smiled. Others looked uncomfortable. Up to that ripple of recognition I had been holding my audience. From that point on, the event belonged to them.

![Lorcan Collins [Lorcan Collins] - 1916: The Rising Handbook](/uploads/posts/book/143326/thumbs/lorcan-collins-lorcan-collins-1916-the-rising.jpg)