The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

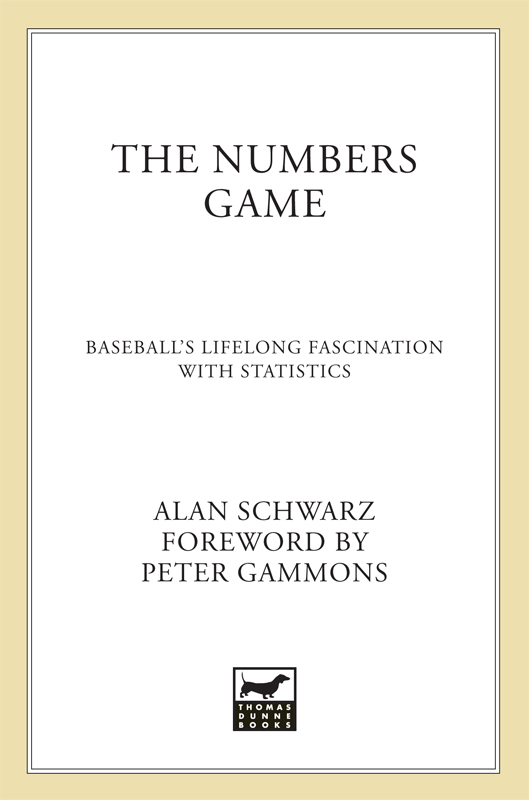

Contents

To everyone who taught me well

Foreword

By Peter Gammons

Grady Little called it his gut. It cost him his job.

In October 2003, Little, then manager of the Boston Red Sox, found his team perilously clinging to a 52 lead over the New York Yankees in the decisive seventh game of the American League Championship Series. With one out in the eighth, Boston just five outs from its first World Series since 1986, New York began to rally against the Red Sox ace, Pedro Martinez. Little decided to keep Martinez inand the move immediately backfired. The Yankees pounded Martinez for three runs to tie the score and went on to win the game and the series, while LittleBostons new Bill Bucknerwas left with a decision to defend.

Little said he was simply holding fast to his instinct, that this was Pedro Martinez, after all, the best pitcher on the team. But his bosses knew better. Bostons general manager, Theo Epstein, knew that all season, after passing the 100-pitch mark, Martinez was a ticking bomb. Before that point his statistics confirmed him as one of the best pitchers in the history of baseball; afterward, nothing close. The Red Sox owner, John Henry, knew this, too. He didnt become a billionaire hedge fund operator without knowing a little something about data and predictability. Little had chosen to go with his gut over what the numbers unequivocally demanded. He lost his job soon thereafter.

It wasnt long before columnists who canoe in the mainstream lampooned the Boston front officewhich also includes the high priest of statistical analysis, Bill Jamesas leaders of the Stat Freak Era. Epstein didnt play college or professional baseball, graduated from Yale, has a law degree, and respects statistics, so he is (in the words of one New York columnist) a geek. This went beyond Boston: Scouts, writers, and other traditionalists have railed against Michael Lewiss 2003 bestseller, Moneyball, which examined the way Billy Beane and his two Harvard-educated assistants, Paul DePodesta and David Forst, used statistics and predictability studies to run the Oakland Athletics.

These folks have it all so wrong. When will they realize this is anything but new?

Critics didnt want to hear that the As philosophy was ushered in two decades ago by Sandy Alderson, a Dartmouth and Harvard Law School grad who rebuilt the Oakland operation around on-base percentage. Or that two future general managers (Danny Evans of the Dodgers and Doug Melvin of the Brewers) cut their front-office teeth on statistical computer systems in the early 1980s. The Chicken Littles who complained that baseballs sky was falling conveniently forgot that Earl Weaver kept batterpitcher breakdowns on index cards, and that Whitey Herzog, who believed that defense won more games than statistics showed, used to sit in his office every day and chart every ball hit during his games. Or that the brilliant Branch Rickey used a Canadian statistician, Allan Roth, in the 1940s to help run the Brooklyn Dodgers. Or that all the way back to the 1860s, writers such as Henry Chadwick were fiddling around with newfangled defensive statistics.

Then again, chances are that the people complaining havent forgotten about this stuff. They never knew it in the first place. Thats what makes the book youre holding so important.

Alan Schwarz has written one of the most original and engrossing histories of baseball you could ever read. He traces the evolution of Americas pastime through its obsession with statistics, which has bubbled over since day onefrom Henry Chadwick to the Bill James generation and beyond, with all sorts of captivating stops in between. The nasty fights over Ty Cobbs batting averages. The birth of statistics houses like the Elias Sports Bureau and STATS Inc. The unending debates over which statistical widgets work best. If you read today that batting averages are worse than worthless, youd assume it came out of the mouth of James, Epstein, or some other modern stathead, right? Nope. It was F.C. Lane of Baseball Magazine, almost a hundred years ago, before he launched into a two-part series that invented a whole new set of illuminating statistics. If theyd had salary arbitration cases at the turn of the century, Lane would have been right there, banging on the numbers just like the geeks do today.

Whether professionals or not, so many of us fans grew up playing with baseball statistics, so much so that we got higher SAT scores because they taught us to think mathematically before the third grade. We played those wonderful tabletop statistics games like All-Star Baseball (invented by my cousin, Ethan Allen) and Strat-O-Matic. An entire generation grew up on Bill Jamess Baseball Abstract series and the Elias Baseball Analysts. These folks arent all geeks, by the way; John F. Kennedy kept the 1961 Baseball Register in his White House desk drawer his entire presidency.

Statistics have been an integral part of baseball for more than 150 years, studied and sanctified in ways few fans (and industry insiders) have ever known. This book should change that.

Henry Chadwick would have loved it. He would have fired Grady Little, too.

Introduction

When you get right down to it, no corner of American culture is more precisely counted, more passionately quantified, than the performance of baseball players. Television advertisers decide how to spend $30 billion a year based on information from just 5,000 Nielsen boxes. The U.S. Census aims only to be a pretty good estimate. Even the counting of presidential votes has been unmasked as shockingly murky. But baseball statistics? They are recorded, analyzed, and memorized with an exactitude that humans summon only for matters so, well, so important.

We know that in 2003 Alex Rodriguez slugged .555 with men on base, hit 3 doubles on 21 counts, and had a .859 zone rating at shortstop. We can look up that Nolan Ryan had 1.78 groundball-to-flyball ratio in 1974, and yielded batters a .295 on-base percentage with the bases loaded. Dozens of these and other categories appear in newspapers and on Web sites every single day of the baseball season, updated to the instant, for every one of a thousand players. Eventually, the best of these numbers ascend to a meaning well above the simple digits that comprise them: The number .406 is Ted Williamss 1941 batting average, 56 the length of Joe DiMaggios hitting streak. The list goes on: 61 4,256 1.12 755. These numbers tell the stories of players and pennant races in a manner that words, photographs, and videotape never do. Baseball and its statistics are inseparable, as lovingly intertwined as the swirls of a candy cane.

And the funny thing is, they always have been. Most fans assume that baseballs infatuation with statistics is a modern phenomenon, a product of the computer age. But it is not, not by a longshot. Arguments over the relative merits of batting average and fielding percentage, runs scored and runs driven in, date back to the games earliest days in the nineteenth century, with annual scrambles to invent new measures. (One writer back then feared that baseball will be brought down almost to a mathematical calculation.) And while many people believe that the serious study of baseball statistics was invented by Bill James in the 1980s, the science he made famous has consumed people from chemists to crackpots for more than a century. I wanted to read a book about all this, about baseballs lifelong passion for its numbers, but it didnt exist. So I decided to write it.