ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I wish to extend my sincerest thanks to everyone who has assisted in the creation of this book. This includes each and every person who posed, indulged, argued, listened or entertained my odd ideas for photographs. Specific thanks are due to Roger Buchannan and Beytan Erkmen for reading the drafts and lending me their technical expertise. Thanks to the publishers for their guidance, support and faith during the production of this book and my colleagues at UCA for their enthusiasm and support.

By far, the greatest and most humble thanks are due to my wife Kelly-Marie for her limitless patience and tolerance of my unreasonable working hours, critical proofreading, and posing for many of the photographs included within this book. Thank you also to my daughter Rose, who was born midway through the writing process. She has perched on my lap, sometimes quietly, as Ive written into the small hours.

IMAGE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Figs . All other photographs copyright retained by the author.

Fig 2

Tim Savage ().

Chapter 1

Inspiration

What makes a good photograph? |

Composition and shooting tips. |

Sharing, learning and reflecting upon your own photographs. |

I n recent years photography has increased exponentially in popularity, with almost everyone owning a camera of some type. Whether it is a DSLR, compact, hybrid or even a mobile phone or tablet camera, digital technology continues to produce better, faster, cheaper, smaller and more feature-rich options. Indeed, few would argue against the fact that photography has become a great deal easier than it was a decade ago. In the days of film, a photographer would be required to load the film, specify the film speed, compose the scene, focus the lens, and specify the exposure using a combination of aperture (the size of the hole that admits light) and shutter speed (the length of time the hole is open) in relation to the meter reading. If using the flash, calculations would be required in relation to the distance between camera and subject. After each exposure the film would need to be wound forward manually, before eventually being rewound, removed, processed and printed, incurring both financial cost and time delays. In contrast, modern digital cameras have become so sophisticated that photographers can all but disregard exposure parameters. This flexibility and freedom allows contemporary photographers to concentrate their full attention upon the subject, timing and composition. Within seconds of the shutter firing, feedback is immediate, with an image being displayed without delay or financial cost.

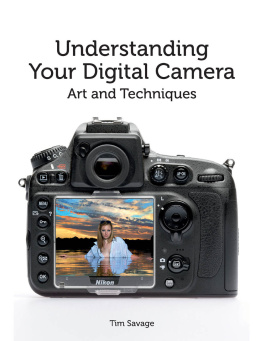

Fig 3

A Digital Single-Lens Reflex camera.

Ease of production is matched by virtually limitless manipulation, duplication and sharing possibilities. Digital photographs can be instantly stylized through a range of enhancements and online tools such as Instagram. These images can then be distributed within seconds. This increase in production and sharing has led to a surge of mediocre images created by photographers using automatic camera settings combined with image-processing algorithms. In order to stand out from the crowd, the creative photographer must seek to rise above this level of mediocrity; to understand the camera and to use it as a tool to realize his or her own vision rather than accept the unexceptional results generated by automated modes.

WHAT MAKES A GOOD PHOTOGRAPH?

A great camera is perfectly capable of taking a poor photograph. A picture may be sharp, well exposed and technically correct, but if it does not engage the interest of the viewer then the photographer has failed. Photography is like food or music, in the sense that an appreciation of it is largely an issue of personal preference. This lack of certainty can be disconcerting to photographers seeking a formula for success and many choose to use the reactions of others to their images as a barometer of success. This can be a useful way of receiving feedback, but the person best qualified to judge the quality of a photograph is the person who took that photograph. Gaining confidence in your own image-making is an essential aspect of becoming a photographer.

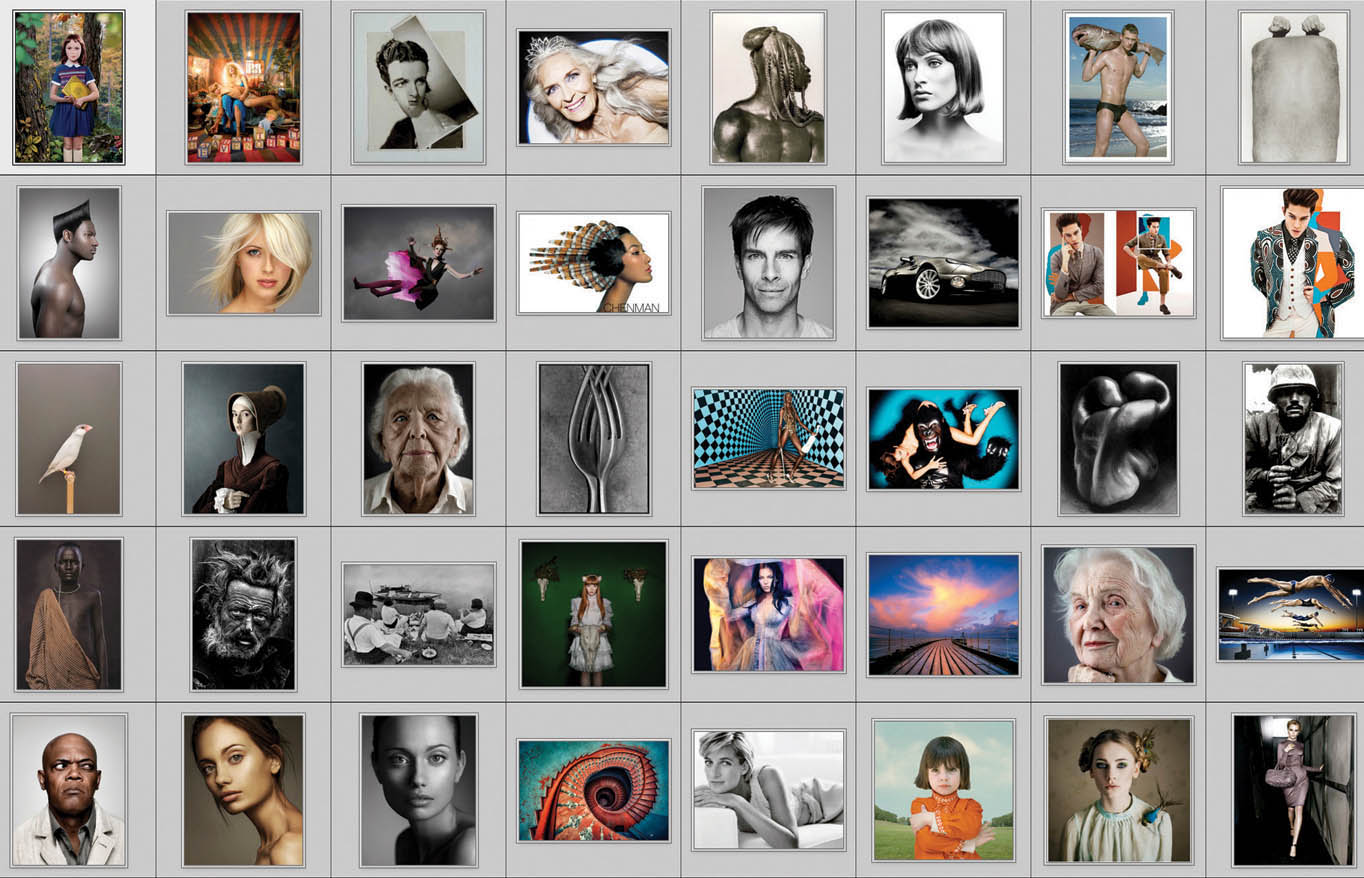

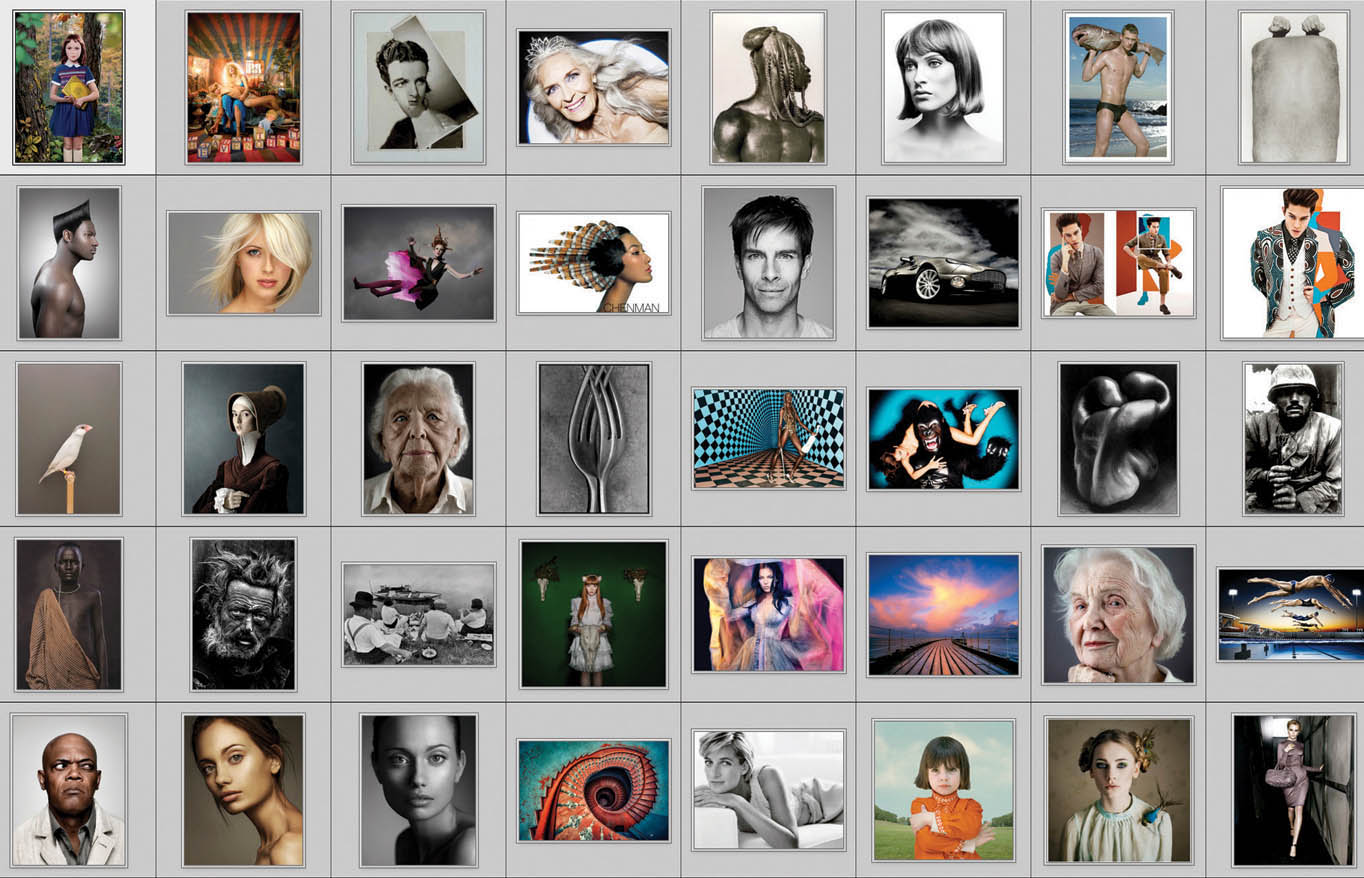

Fig 4

Collecting photographs is an effective way of identifying your own tastes and preferences.

One effective method of defining your own personal taste is to collect photographs. Browse online and in print, magazines, newspapers and social media. Collect and store pictures that stand out. Once a few hundred images have been accumulated it is usually possible to identify some common traits. You may see trends emerging in features such as subject, lighting, focus, depth, textures and colour. For example, textures rendered in black and white could be a recurring theme, or perhaps isolated areas of focus within portraiture. Once you have identified your own personal tastes, they can be consciously applied when creating images.

COMPOSITION AND SHOOTING TIPS

Understanding personal taste is the first step towards making work that will appeal to your own preferences. For many students of photography this process begins by considering composition. Composition refers to the arrangement of the key elements within the boundaries of the photographic frame. There are numerous rules and guides that can assist with geometric aids to production. For readers interested in compositional theory an online search for the golden section will provide detail of the mathematical formula commonly used within the creative arts. The golden section underpins the photographers rule of thirds (see ). In terms of compositional theory there are a few simple pointers that, when combined with the lessons learnt from collecting images, may help when you are seeking to improve the aesthetics of your images.

First, when framing a subject, you should be clear and bold about what the image is about. The job of the photographer is to direct the eye of the viewer. the photographer moved closer to the model and shot from an angle that provided a less distracting background. The flash was used to lighten facial shadows and provide a catch light in the eyes. These changes provide a clearly defined subject and background, and a better picture.

Figs 5 and 6

Keeping the composition simple avoids distracting elements within the frame.

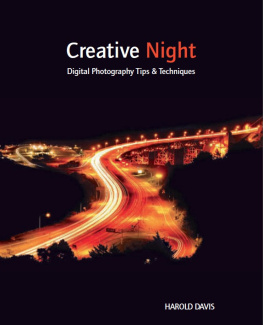

Having considered the way in which the viewers eye engages with the subject, consider how, once the eye has landed within the composition, it explores out towards the boundaries of the frame. Does attention drift towards the edges or is interest focused upon a specific point? Using lines is an effective way of directing the path of the eye. In , the lines naturally present combine with perspective to draw the eye towards the centre of the photograph into the main subject.

Fig 7

Lines and contrast can be used to direct the viewers eye within the composition.