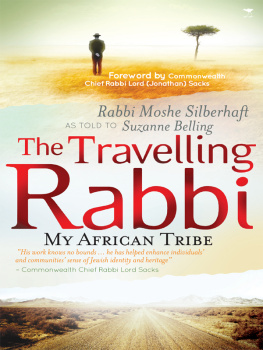

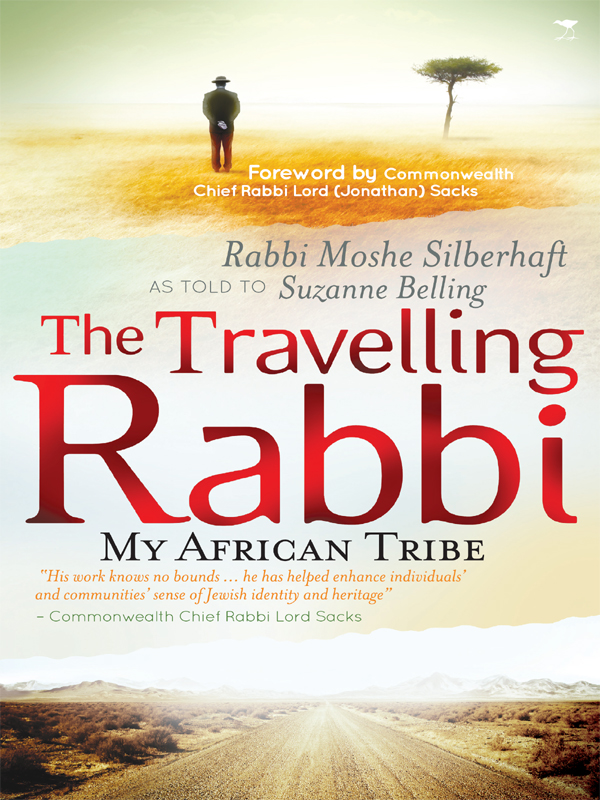

Foreword

by Chief Rabbi Lord Sacks

I have known of Rabbi Silberhafts work for some time and have been privileged to have met him and to have learned of his experiences. As spiritual leader of the country communities of the South African Jewish Board of Deputies and African Jewish Congress for the past 18 years, his work knows no bounds. No request is left undealt with, no matter how small or how large. In the troubled circumstances in which he has operated, Rabbi Silberhafts dedication and personal care are deeply appreciated by all with whom he has come into contact and who unhesitatingly speak of his enthusiasm and his devotion to duty.

I am well aware of the comfort and security he has given to so many people, over so many years, who are isolated and need the spiritual and practical guidance that Rabbi Silberhaft has so ably given. His concern for the lives of so many and his ability to relate to each individual and become their friends are quite unique. Throughout this time, Rabbi Silberhaft has been the personification of that famous Talmudic phrase; Kol Yisrael arevim zeh la-zeh all of Israel are responsible for one another.

Without his commitment and enthusiasm, which comes, at times, at considerable personal sacrifice for his family, many communities would cease to exist. Reading this book, it is so heart-warming to see how much he has done to ensure that people are able to survive that their welfare is properly taken care of and their simple needs for food and money are properly dealt with.

Continuously travelling across the length and breadth of half the African continent, Rabbi Silberhaft or the Travelling Rabbi as he has become known has reached out to every Jew in love. In doing so, he has helped enhance individuals and communities sense of Jewish identity and heritage, connecting them to fellow Jews throughout the ages.

We read in the Torah Judaisms most sacred text of Moses great speech to the Jewish people just before they entered the Promised Land more than 3,000 years ago. Moses had led the Jewish people out of Egypt and out of slavery. For the previous forty years, he had led them through the Wilderness. But it had not been an easy journey. The Jewish people were not a nation to inspire confidence. They were quarrelsome, ungrateful, indecisive and, at times, disloyal. Yet, despite this, Moses sensed that something great had happened to them, something whose significance went far beyond that time, that place and this people. He believed, he knew , that this people would be the carriers of an eternal message, one that would have an effect not only on itself but on the civilisation of the world. But only if successive generations of Jews took it upon themselves to hand down their beliefs to their children and their childrens children.

Just before Moses said these words he made an even more poignant request: You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might (Deuteronomy 6:5). The sixteenth-century commentator Rabbi Moses Alshekh was surely right when he said that these two verses are connected. We can pass on to our children only what we ourselves love (Moses Alshekh, Torat Mosheh to Deuteronomy 6:6).

We cannot order our children or anyone to be Jews. We cannot deprive them of their choice, nor can we turn them into our clones. All we can do is show them what we believe and let them see the beauty of how we live.

Throughout his 18 years of service, and as is shown in this book, Rabbi Moshe Silberhaft has helped countless numbers of Jews experience the beauty of Judaism. He understands that the Jewish people has survived not just because of an inheritance of faith, but rather because Judaism has been brought alive in each generation and then handed on to those generations not yet born.

What is evident from reading this book is that Rabbi Silberhaft has a clear purpose to his work, to his travels, to his life: to ensure people love God, love Judaism and love simply being Jewish. Nothing could be simpler. Nothing could be more beautiful. And, as you will read, few people do this better than the Travelling Rabbi, Rabbi Moshe Silberhaft.

Chief Rabbi Lord (Jonathan) Sacks

April 2012/Nissan 5772

Preface

by Mandy Wiener

It is by no mere coincidence that as a 14-year-old yeshiva bocher in the 1980s, Moshe Silberhaft found himself journeying to a far flung town in the very northern reaches of the country to assist in celebrating chagim , the Jewish festivals. As the prolific Holocaust survivor and Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel remarked, In Jewish history there are no coincidences. It would prove to be beshiert , an undertaking that would seem to be pre-ordained, destined to happen. It would set him on a life journey that would result in his making scores of similar trips over the next 30-odd years, traversing the countrys roads and byways as he carried the message of Yiddishkeit with him, in his capacity as the rabbi to the country communities in which he is affectionately known as The Travelling Rabbi.

Over the past 18 years in that capacity, Rabbi Silberhaft has encountered all manner of roads along the way and many of those so succinctly mirror the experiences he has dealt with among his community as he serves as its spiritual leader. Each resident of every town that falls within Rabbi Silberhafts congregation has a deeply personal story to tell about a simcha or a tragedy in which he has played a pivotal role, providing guidance and authority where often it is lacking. He has brought a unique intimacy and personal understanding to the office in which he serves, and is considered a friend to most congregants as he features prominently in significant events throughout their life cycles, from a babys bris to his barmitzvah to his marriage, and occasionally to his funeral.

I am privileged to be able to personally attest to this. Rabbi Moshes early travels to the then Northern Transvaal introduced him to the Wieners of Pietersburg and a close friendship developed between his family and mine over the unfolding decades. In a fractious Jewish community, which was waning in its twilight years, Rabbi Silberhaft provided leadership and a sense of belonging. He was a lifeline to a Jewish world so far removed from the one in which we were living and he would continue to provide spiritual and religious guidance to me long after I had travelled the N1 south towards Johannesburg.

As a 12-year-old, I stood before Rabbi Silberhaft in the quaint shul in Polokwane as he presided over my batmitzvah. Sixteen years later, as a kallah under the chuppah in the similarly atmospheric Lions Shul in Braamfontein, Rabbi Silberhaft married my husband and me. He also officiated at the marriages of both of my siblings, and has become a dear friend to my father over the years. He has been present in times of celebration and of difficulty. He has even fulfilled what is surely one of the most bizarre requests made of a country community rabbi hosting my fathers beloved Labrador for a week while my parents prepared to make aliyah !