Editor: Linda Ligon

Translator: David Burrous

Copy editor: Veronica Patterson

Illustrations: Ann Sabin Swanson

Cover design: Susan Wasinger

Interior design: Elizabeth R. Mrofka

Production: Trish Faubion, Nancy Arndt

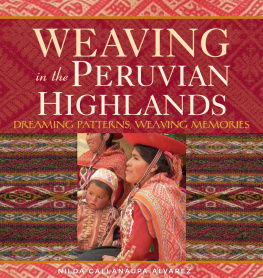

Cover images: Three generations of weavers from Accha Alta, and belt loom weaving from Chinchero.

2007 Center for Traditional Textiles Cusco

All rights reserved.

| Centro de Textiles Tradicionales del Cusco Avenida Sol 603 Cusco, Peru |

| Thrums llc 306 North Washington, 104 Loveland, Colorado 80537 |

Printed in China by Asia Pacific

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Callaaupa Alvarez, Nilda.

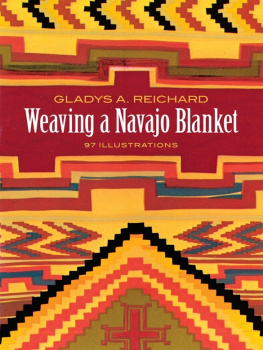

Weaving in the Peruvian highlands : dreaming patterns, weaving memories / Nilda Callaaupa Alvarez.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Summary: Handwoven fabrics comprise the living history and culture of the Peruvian highlands from Cusco to Machu Picchu and beyond. Fabric patterns with evocative names reflect the landscape and events in vivid color, evolving over time. The weavers who create these fabrics in the time-honored way are keepers of the culture and sustainers of a noble but difficult lifestyle in tune with the earth. They raise llamas and alpacas for fiber, collect plants for natural dyes, spin yarn on primitive spindles, and weave acres of cloth on simple backstrap looms just as their forebears have done for thousands of years. They weave clothing, rugs, bedcovers, potato sacks, hunting slings, and sacrificial fabrics for themselves and their villages, and for sale to supplement their meager incomes. Travellers visiting the area (hundreds of thousands a year from North America alone) are drawn to this authentic, well-crafted work and given the opportunity to collect it at every street corner and rail stop. Weaving in the Peruvian Highlands is their guide to quality, understanding, and appreciation. They will learn how pattern names such as meandering river or lake with flowers relate to the geography and history, and how the traditional natural materials and colors enhance the value of the work.

ISBN-13: 978-0-9838860-3-7

1. Hand weavingPeru. 2. Indian textile fabricsPeru. I. Title.

TT848.A7155 2007

746.140985--dc22

2007028581

10 9 8 7 6 5

Dedication

To my family: my husband and my two sons, from whom I took time to do my research.

To my parents, especially my mother, who was an important part of my weaving life. And to all my extended family.

To my foreign friends who shared their cultural and textile experience and appreciation.

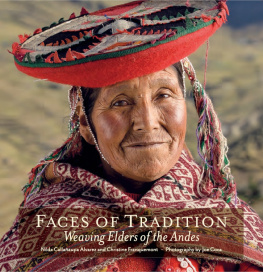

To the weavers in all the communities, especially the elders.

This book is also dedicated to the memory of Edward Franquemont, weaver, scholar, friend.

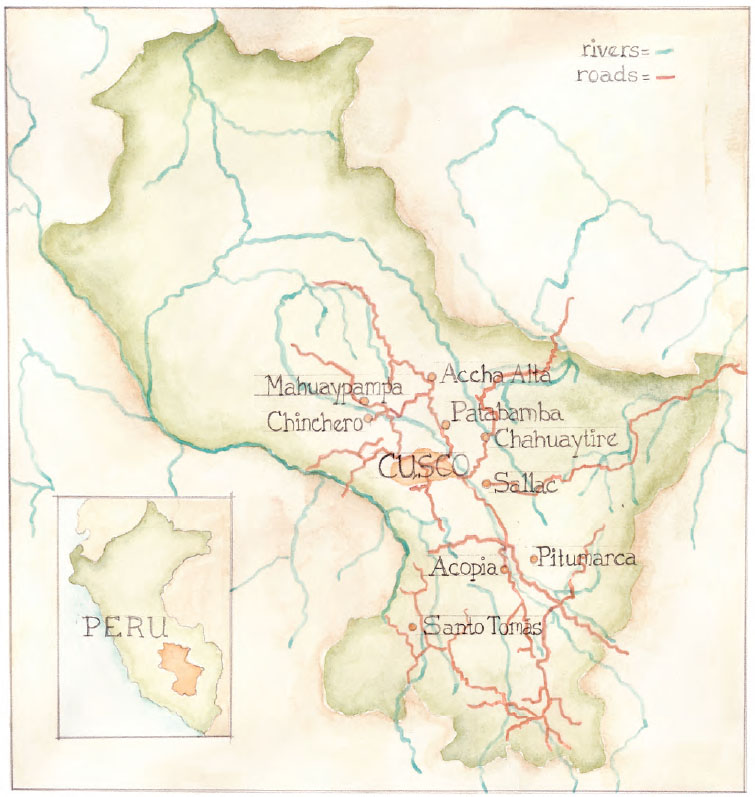

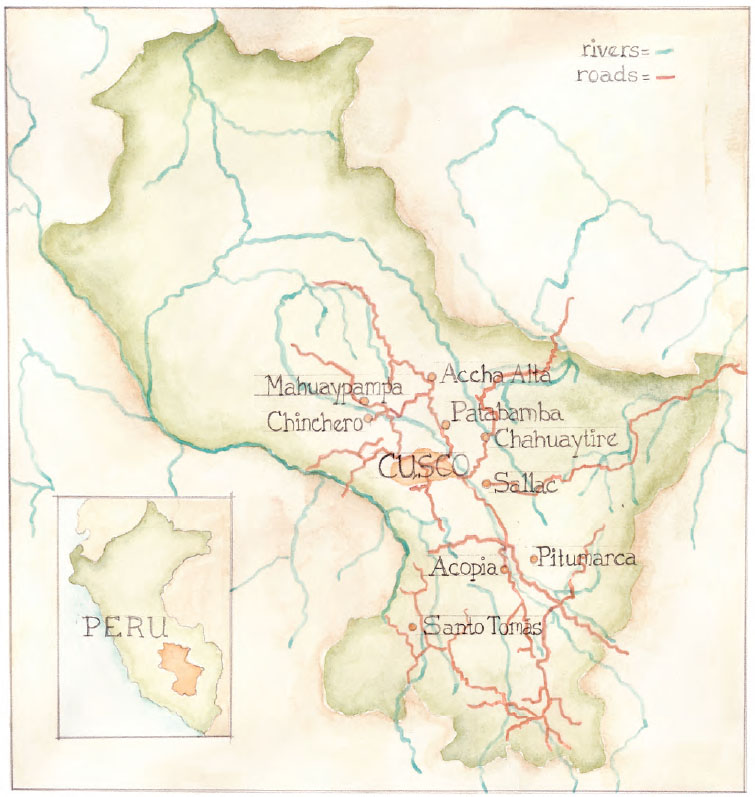

Department of Cusco

An Affirmation of Continuity

I n the winter of 1982, while engaged in ethnobotanical research with a team of anthropologists and botanists, I was fortunate to live among the people of Chinchero, a traditional Andean community located some twenty miles by road from the ancient Peruvian city of Cusco. When I first met Nilda Callaaupa Alvarez and her wonderful family, she was twenty-two but seemed wise beyond her years. I wasnt the only person to sense in her a young woman marked by destiny. She taught all of us many things that first season and has continued for more than twenty-five years to be my friend and guide to the extraordinary Andean world, with its fusion of past and present. In that world, pre-Columbian ideas and themes have been forged into a new amalgam inspired by both the winds of modernity and the pious cloak of Catholicism that has enveloped the mountains for more than 500 years.

Simply put, Nilda is one of the most remarkable individuals I have known. She is a woman who transcends culture, who exists out of time and space, an artist and scholar of immense vision and achievement. But what makes her truly great is her integrity, the fact that despite any number of alluring temptations she has remained utterly grounded in a spirit of place, loyal to community and landscape. More than any other, this trait links her to the distant pastto the archaic memory and currents of ritual that have fundamentally informed her life.

I recall vividly those first weeks in Chinchero. We were there at the invitation of Chris and Ed Franquemont, anthropologists and weavers who had lived in the community for several years and raised their children there. Chris, in particular, had a fascination with plants and would go on to become an authority in Andean ethnobotany. Our immediate task under her leadership was to complete a thorough survey of the useful plants of the Chinchero region, whose small hamlets are spread over some 135 square kilometers at elevations ranging from 3,000 to 5,000 meters.

By day we worked furiously, collecting medicinal herbs on the flanks of the sacred mountain Antakillqa, edible algae from the pools and ponds scattered upon the rich plains and verdant fields of Yanacona and Ayllupungo, exotic ornamentals among the gorges of Yanacona, where wild things thrived and rushing streams carried the rains to the Urubamba, the holy river of the Inca. By night we mostly had fun, drinking and dancing, exchanging kintus of coca leaves and blowing the essence to the wind. Nildas mother, Doa Guadelupe Alvarez, famously asked whether any of us had been born of mothers. She was perhaps reassured about us on the day when we stood side by side beneath the vault of the church, in a space illuminated by candles and the light of pale Andean skies, with newborn children in our arms. We held boys and girls swaddled in white linen as an itinerant priest dripped holy water onto their foreheads and spoke words of blessing that brought the infants into the realm of the saved. That afternoon three of us became godfathers, assuming ties of expectation and reciprocal obligations that would forever link us to the community. From me, my compadres hoped for support for my godchilds education, perhaps the odd gift, a cow for the family, a measure of security in an uncertain nation. From them, I wanted the chance to know their world, an asset far more valuable that anything I could offer. It is a relationship that I have always cherished.

Though the highland flora was spectacular and the agricultural skills of these descendants of the Inca nothing short of genius, what impressed me most about Chinchero was the daily round, the accumulation of gestures that together spoke of an intimate and profound reverence for the very soil upon which the village lay. The village, of course, was not merely the adobe and thatch houses clustered around the small church. It was the totality of the peoples existencethe ancient ruins that ran away from the village and hung like memories at the edge of cliffs overlooking the river, the fields cut into the precipitous slopes of Antakillqa, the lakes on the pampa (plain) where sedges grow, and the waterfall where no one went for fear of meeting Sirena, the malevolent spirit of the forest.

For the people of the village, every activity was an affirmation of continuity. At dawn, the first member of the family to go outside formally greeted the sun. At night, when a father stepped back across the threshold into the darkness of his small hut, he invariably removed his hat, whispered a prayer of thanksgiving, and lit a candle before greeting his family. Before the morning labor in the fields began, there were always prayers and offerings of coca leaves for Pacha Mama (Mother Earth). The men worked together in teams forged not only by blood but by reciprocal bonds of obligation and loyalty, social and ritual debts accumulated over lifetimes and generations, never spoken about and never forgotten. Sometime around midday, the women and children would arrive with steaming cauldrons of soup, baskets of potatoes, and flasks of

Next page