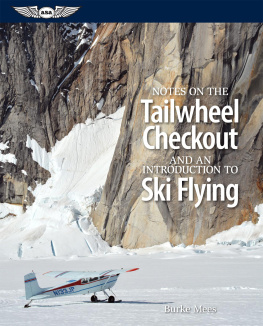

Notes on the Tailwheel Checkout and An Introduction to Ski Flying

Burke Mees

Aviation Supplies & Academics, Inc.

7005 132nd Place SE

Newcastle, Washington 98059-3153

asa@asa2fly.com | www.asa2fly.com

2014 Aviation Supplies & Academics, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher and Burke Mees assume no responsibility for damages resulting from the use of the information contained herein.

None of the material in this book supersedes any operational documents or procedures issued by the Federal Aviation Administration, aircraft and avionics manufacturers, flight schools, or the operators of aircraft.

All photographs, including those on the cover, are Burke Mees, unless otherwise noted.

ASA-NTC-EB

eBook ISBN 978-1-61954-191-7

LoC 2014030477

To all my tailwheel and ski students, who provided the occasion for me to develop and organize my thoughts on these topics, without whom this book would not have been possible.

Introduction

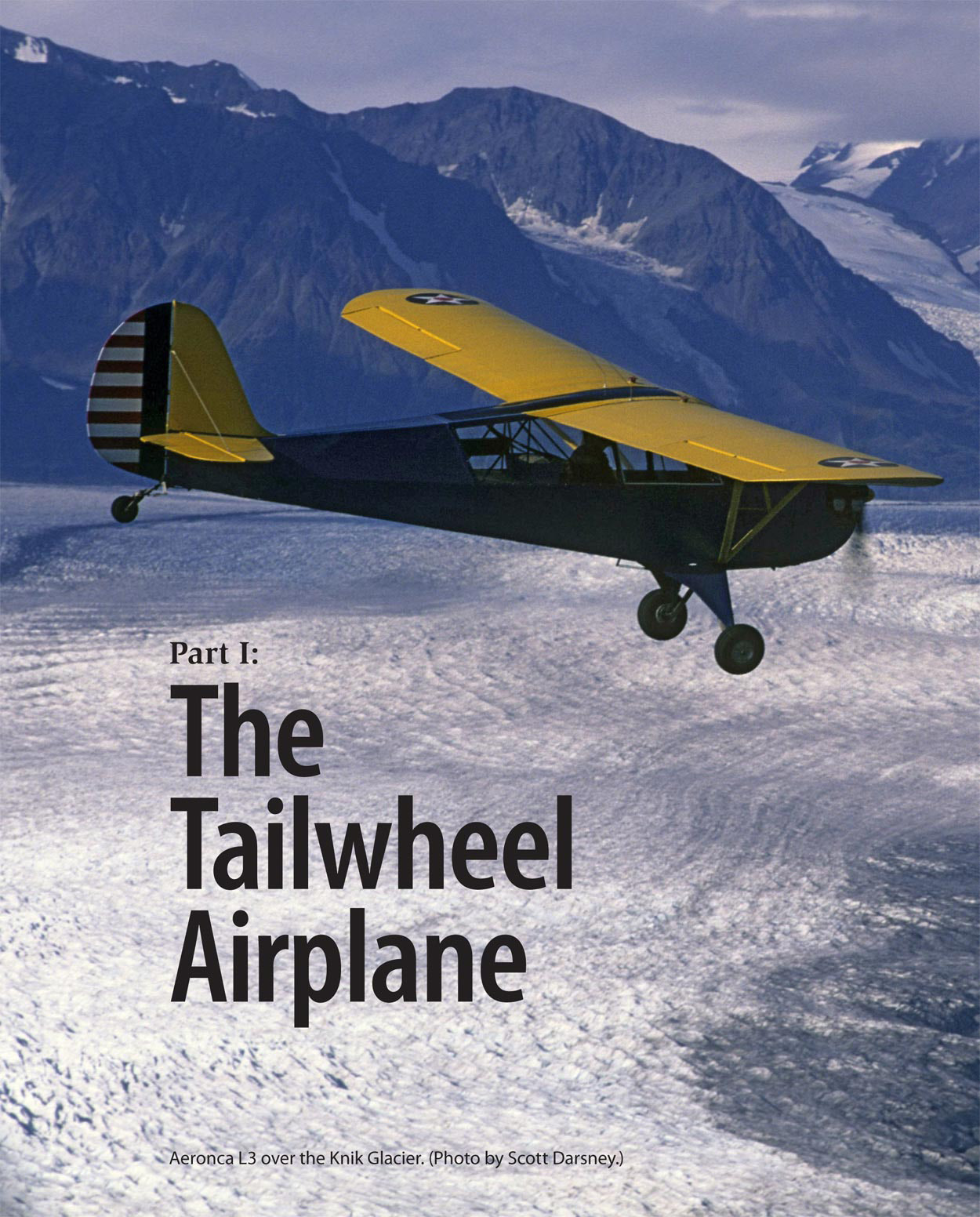

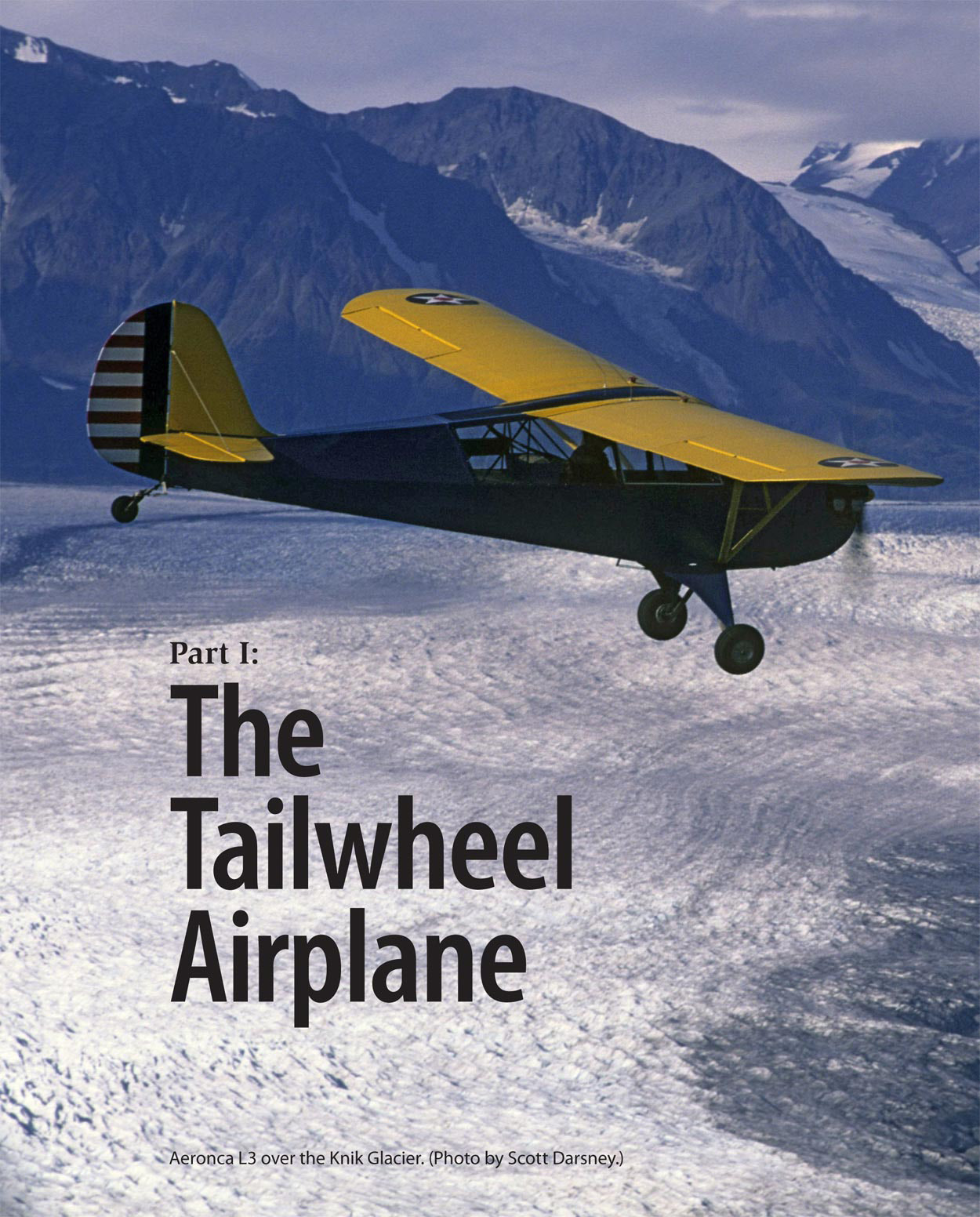

I remember when I wrote my first book, Notes of a Seaplane Instructor, somebody asked if I was planning on writing another one. Without the slightest hesitation I replied that I hoped not because I never want to spend that much time at a desk again. But then it did happen again, and not because I wanted to write another book but because it became apparent that it should be written. I was doing a tailwheel checkout in an Aeronca L-3 when I realized that over the years, I had explained these topics enough times that I should write them down. In the course of instructing you come to know what explanations work best and you continually hone them to be more concise and more effective. Then next thing you know, you find yourself in possession of the material for a book.

This project first took the form of a story. I presented the instructional information in the voice of a student learning to fly tailwheel airplanes in the context of an extravagant and humorous action-adventure novel. That book is called The Lost Art. It was good fun and has been selling locally in Alaska, but I decided to expand that material, adapt it to the standard textbook format, and add supporting illustrations, which brought this book to its present form.

I was working on this project over the winter and decided that, as a related topic, I would include a section on ski flying. Most skiplanes are tailwheel airplanes and in the northern latitudes, ski flying is a seasonal variation of tailwheel flying. A lot of people fly a tailwheel airplane on wheels in the summer, and then put the same airplane on skis in the winter. A tailwheel checkout is often followed up with a ski checkout and I keep to that same sequence of events in this book.

Tailwheel and ski flying have something else in common: they are both niche topics that are out of the aviation mainstream. There is not much written material available about either of them and this book does something to correct that. It covers the basics for an initial tailwheel and ski checkout, but it also contains commentary on the finer points of these topics. It is meant not only to be useful to the beginner first making the transition, but also to provide insights to the pilot or instructor already flying these kinds of airplanes.

At the end of this book, I included a brief treatment of two specialty topics: multi-engine tailwheel airplanes and ski flying on glaciers. Since these arent necessarily relevant to the basic checkout, I kept them separate from the main text as appendices.

I have a special appreciation for both tailwheel and ski flying, and Ive put a lot of time and effort into organizing my checkouts. I hope that shows through in this book and I hope you learn something useful here.

Burke Mees

September 2014

Anchorage, Alaska

Why Tailwheel Airplanes?

On the topic of tailwheel airplanes, people sometimes ask why they are still around anyway. Isnt the nosewheel design more stable, easier to fly, and just generally safer? Why would anyone want to fly an inherently unstable airplane when there is a greater chance of a mishap?

It turns out that the tailwheel design has some real advantages when it comes to rough or unimproved landing areas. The tailwheel design is lighter, mechanically simpler, and more rugged than the nosewheel design. The propeller has more ground clearance and the tailwheel airplane can handle rougher surfaces and take more abuse than the relatively delicate nosewheel airplanes. Perhaps the tailwheel airplanes greatest advantage is that on landing it can use lower pitch attitudes and better manage wing lift in a way that is appropriate for off-field work. Additionally, when it comes to ski flying, the tailwheel airplane is a generally better design for reasons that will become evident later on in this book.

It is no coincidence that the tailwheel configuration was the design of choice in the early days of aviation when unimproved landing areas were the norm. It wasnt until we developed an aviation infrastructure and most flying was done from airport to airport that nosewheel airplanes began to seriously come onto the scene. Today, tailwheel airplanes are still the preferred choice when flying to unimproved strips.

There is another reason why tailwheel airplanes are still relevant in the modern world: they involve a very basic, hands-on kind of flying. With all the improvements of newer airplanes, flying can become a matter of just doing things by the numbers or managing the automation, and the old stick-and-rudder airplanes can bring us back to the basics. They keep us engaged with the airplane, focus our attention on basic airmanship, and continually provide opportunities to hone our skills. For this reason, the time we spend in tailwheel airplanes can benefit the rest of our flying.

Aside from their practical benefits, another reason to fly tailwheel airplanes comes down to personal satisfaction. A lot of the old airplanes have a good feel and are just enjoyable to fly.

What about the idea that tailwheel airplanes are less safe? They are certainly demanding of good technique, but as long as we develop and maintain our proficiency, there is nothing unsafe about them. If their demanding nature forces us to hone our skills and focus attention on basic aviating, then in the end they probably make us safer. The nosewheel design has become the standard but it certainly hasnt made the tailwheel airplane irrelevant or obsolete.

The Preliminaries

When doing a tailwheel checkout, before we get in the airplane, I spend some time talking about what I call the preliminaries: stability, weathervaning, adverse yaw, and angle of attack. This provides background information on tailwheel topics, explains some differences between the nosewheel and tailwheel design, and lays the groundwork for flight training.

Stability

The first topic I cover is the airplanes yaw stability on the ground and how the nosewheel and tailwheel airplane differ in this respect. Stability has to do with how the airplane responds to a disruption. In the case of yaw stability, if an airplane deviates from a straight path and it tends to straighten itself out on its own with no pilot input, then the airplane exhibits positive stability, which is the case with nosewheel airplanes. On the other hand, if that same initial yaw deviation gives rise to forces that act to increase the deviationso that left on its own with no corrective action from the pilot the airplane would swing entirely out of controlthen the airplane exhibits negative yaw stability, which is the case in tailwheel airplanes.