Acknowledgments

To Mary Ann Hall, my editor who first contacted me with the idea and was amazing through the entire process; for answering endless questions and responding so graciously; for her continuous encouragement and reaffirmationThank you, Mary Ann.

To Rachel Saldaa, photographer and dear friendfor the talent she brought to this project, for working long photo-shoot weekends, camping out, and for getting in my face and making us laugh.

To all the hands at Quarry that helped put the pieces of this book into one beautiful entirety including Betsy Gammons for her project management, David Martinell for his art direction, and to the designer, Nancy Bradham.

To the artists who contributed their wonderful work to the galleryThank you!

To the readers of my blog, for their loyalty and kindness.

To dear friends: Shari, for her letters full of poetry and inspiration that helped spur me on. To Alica, for her friendship and enthusiasm. To Alicia, for checking in and noticing. To Emily, for silently cheering in my corner.

To my co-teachers at The Lawrence Arts Center for their moral support.

To G. Webb, my first watercolor instructor.

To Paul Hartley (19432009) an amazing painter and professor, for teaching me about composition, ways of combining imagery, and for inspiring Project 12 in this book.

To Tanya Hartman, my graduate school professor who taught me about making paint by hand, to make every part of the painting interesting, and that without fullness of life, there is no art.

To my sister, for being who she is: lovely.

To my parents for searching and searching to find the photo, for giving me my first box of paints, years of endless encouragement, and so much more.

To my husband for continually believing in me, for always listening, and for helping me since the day we met.

ABOUT THE

AUTHOR

Heather Smith Jones is a studio artist and instructor who earned her MFA from The University of Kansas in 2001 and her BFA from East Carolina University in 1996. Smith Jones is represented by galleries nationwide and has completed residencies at Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts and Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. Her work is in the public collections of the Sprint Corporation and Emprise Financial Corporation and in many private collections. Smith Jones also collaborates with other artists in photography and multi-media projects. She lives in Lawrence, Kansas, with her husband.

www.heathersmithjones.com

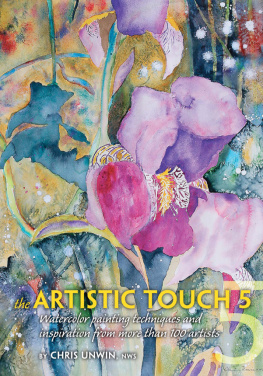

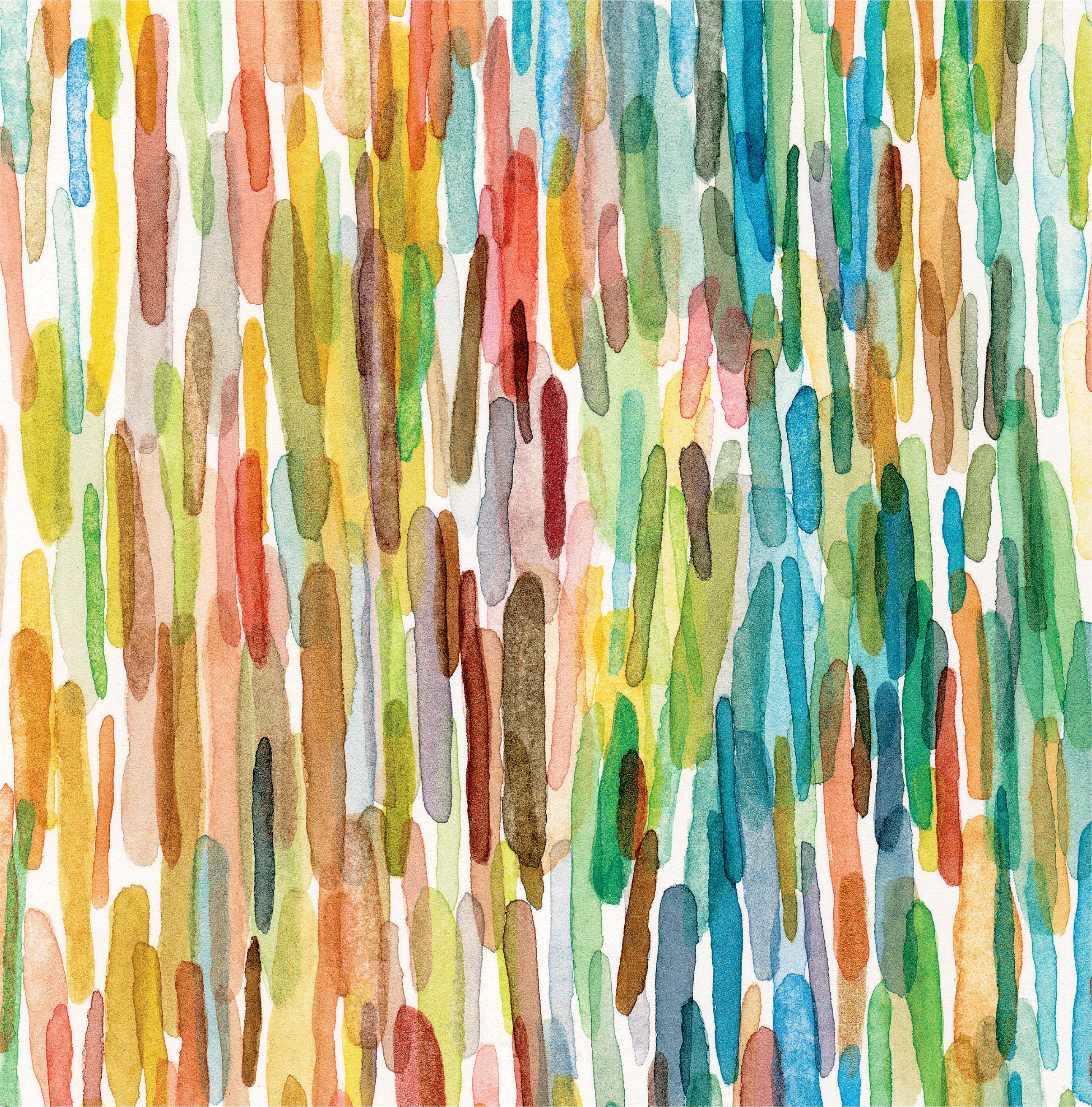

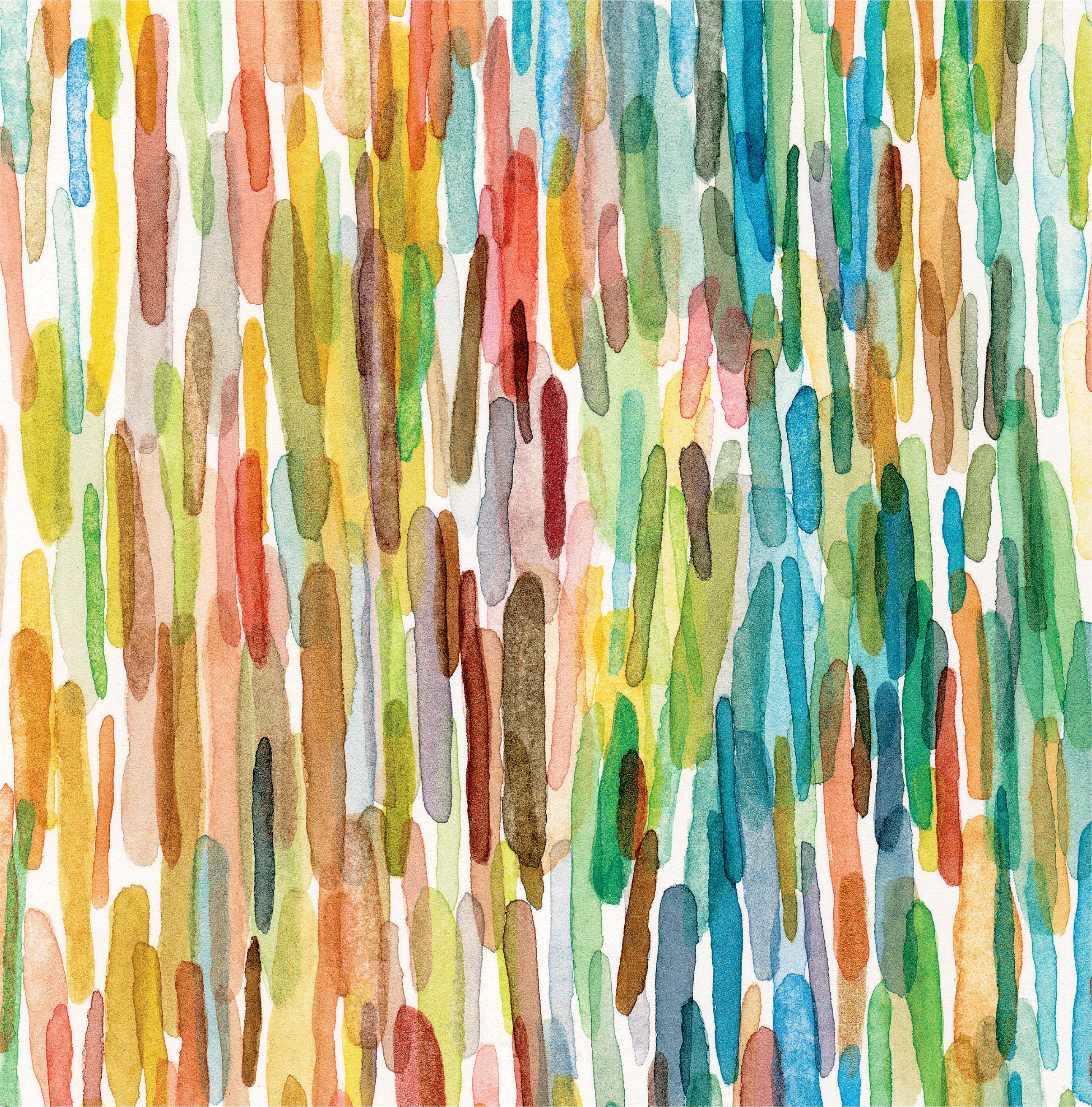

(Right) Layers, (detail), watercolor on paper, 10 x 11 (25.4 x 27.9 cm).

CHAPTER ONE:

BASICS

Not everyone has had the opportunity to experiment with watercolor as a child or even as an adult. If you want to try painting with watercolor for the first time and wonder how to begin, take a few moments and read the basics chapter which discusses paper, paint, palettes, and brushes. Become familiar with the materials and how to set up for a painting session.

The paper section discusses the different types, how it is made, and how to prepare paper before painting. The paint section covers the three types of watercolor used in Water Paper Paint, as well as how to make your own paint. The palettes section is comprehensive and begins with examples of palette supports and ends with a discussion about the color wheel and color systems. You will also learn about the characteristics of color, how manufacturers label paints, and a suggested selection of paint colors with which to begin painting. The brush section introduces the types of brushes, how to use them, and the numbering system manufacturers use for sizing. It includes a suggested list of brushes to use for the projects chapter of the book and some simple tips for brush care.

PAPER

The projects in Water Paper Paint use three main types of paper: rough, cold-press, and hot-press. These terms refer to the surface quality or smoothness of the paper. Well review the substrate options, their characteristics, and how to use them on the following pages.

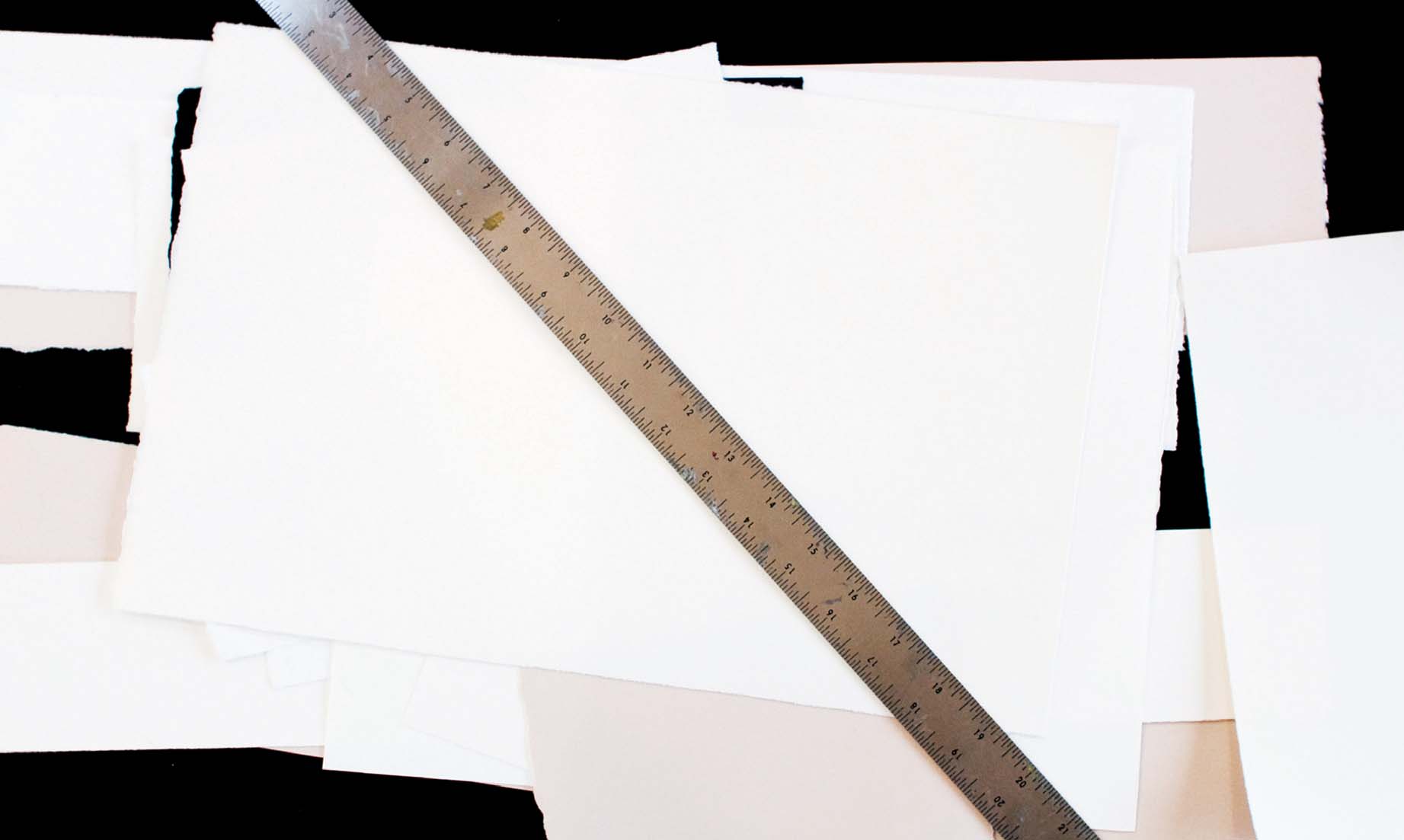

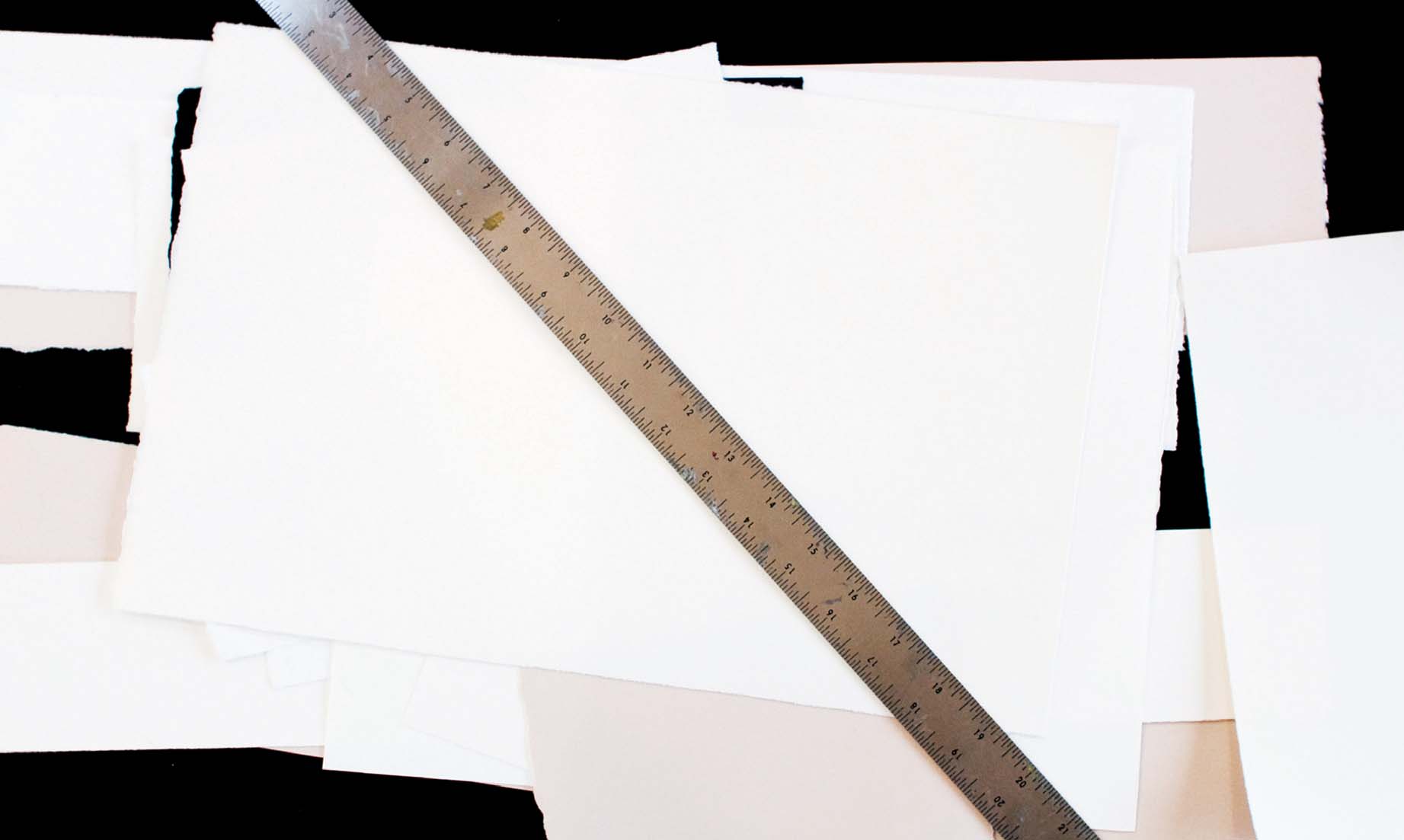

Watercolor paper types (left to right): rough, cold press, soft press, hot press

Paper Types

For centuries, fine paper makers have used a mold to form the sheets. A mold is a wooden frame with a fine screen stretched across it. It is dipped into a mixture of cotton fibers, sizing, and water and when lifted, it holds what will be the sheet of paper. As the fibers dry they bind together. The irregular border of the fibers form what is called a deckle edge. Today the screens used to make paper are much longer, so once cut to size, watercolor papers may have a combination of deckled, cut, or torn edges.

Cotton fibers, or linters, are used in making watercolor paper instead of tree fibers. Tree fibers have been found to yellow over time as the paper becomes more acidic from exposure to ultraviolet light. Substances like calcium carbonate are added to the cotton pulp to make it more alkaline and increase the life of the paper.

Once the sheets are made, they are rolled through cylinders to press the paper fibers. Cold cylinders produce cold-press paper, a sheet with a texture between rough and hot. Cold-press paper (CP) is a popular choice among watercolor artists. Hot cylinders make hot-press paper (HP) a paper with a smooth and satiny finish. Hot-press paper is a good choice for work that involves detail either in drawing or paint. Rough press paper is not pressed, giving it a very toothy grain. Generally, rough paper is suited for wet-into-wet techniques since the surface is highly absorbent. Because it is also very durable, it is a suitable choice for mixed-media work. In addition, some paper makers, such as Fabriano, make a soft press paper, which has a velvety surface, offering a version between hot-press and cold-press.

During the paper-making process, manufacturers size the paper sheets with natural or synthetic gelatin. The sizing permeates the paper to allow for better paint adhesion and vibrancy of color. It also makes the paper more durable and less absorbent to excess water when painting.

Preparing Paper

Stretching watercolor paper before painting is sometimes necessary to prevent rippling. While some artists do not mind paper rippling, it is helpful to know what causes it. Two factors help determine if stretching is needed: the weight or thickness of the paper and the intended painting process. Watercolor paper is available in sheets, rolls, and blocks and is measured in pounds per ream (lb) or grams per square meter (gsm). Two common and easily found weights are 140 lb (300 gsm) and 300 lb (640 gsm). Paper of 300 lb or more is very thick and generally sturdy enough without stretching. For paper that weighs less than 300 lb, such as 140 lb or less, the second determining factor warrants consideration. If you intend to saturate the paper with paint, then you should stretch it first. The more water you apply to the paper, the more likely it is to buckle.