Copyright 2019 by Running Press

Interior and cover illustrations copyright 2019 by May van Millingen

Cover copyright 2019 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Running Press

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.runningpress.com

@Running_Press

First Edition: October 2019

Published by Running Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Running Press name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Text by Matt Garczynski.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019938757

ISBNs: 978-0-7624-6770-9 (hardcover), 978-0-7624-6772-3 (ebook)

E3-20190831-JV-NF-ORI

), it would indicate either room temperature or the temperature of the refrigerator shelf you just grabbed the bottle from. But pick up that thermometer and lick it clean, and you could be in for an inferno of pain. Youre not delusional to think that hot sauce is hotor at least no more so than every other person on earth. Its just that hot sauce seems hot to the human mind. And the reason that hot sauce seems hot can be chalked up to a very real phenomenon that involves the way your brain and sensory neurons conspire to perceive heat.

Capsaicin: A Peppers Natural Defense Mechanism

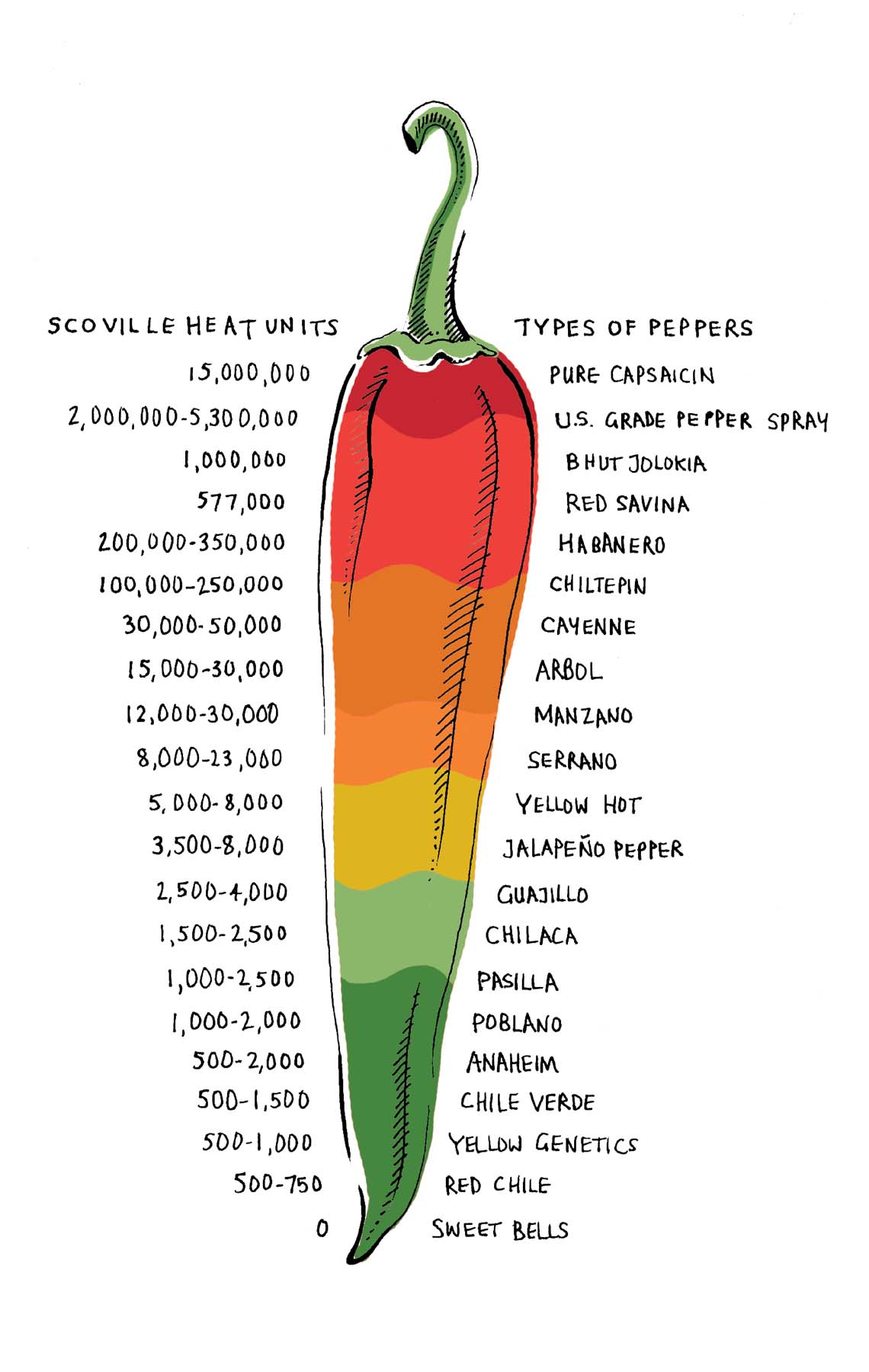

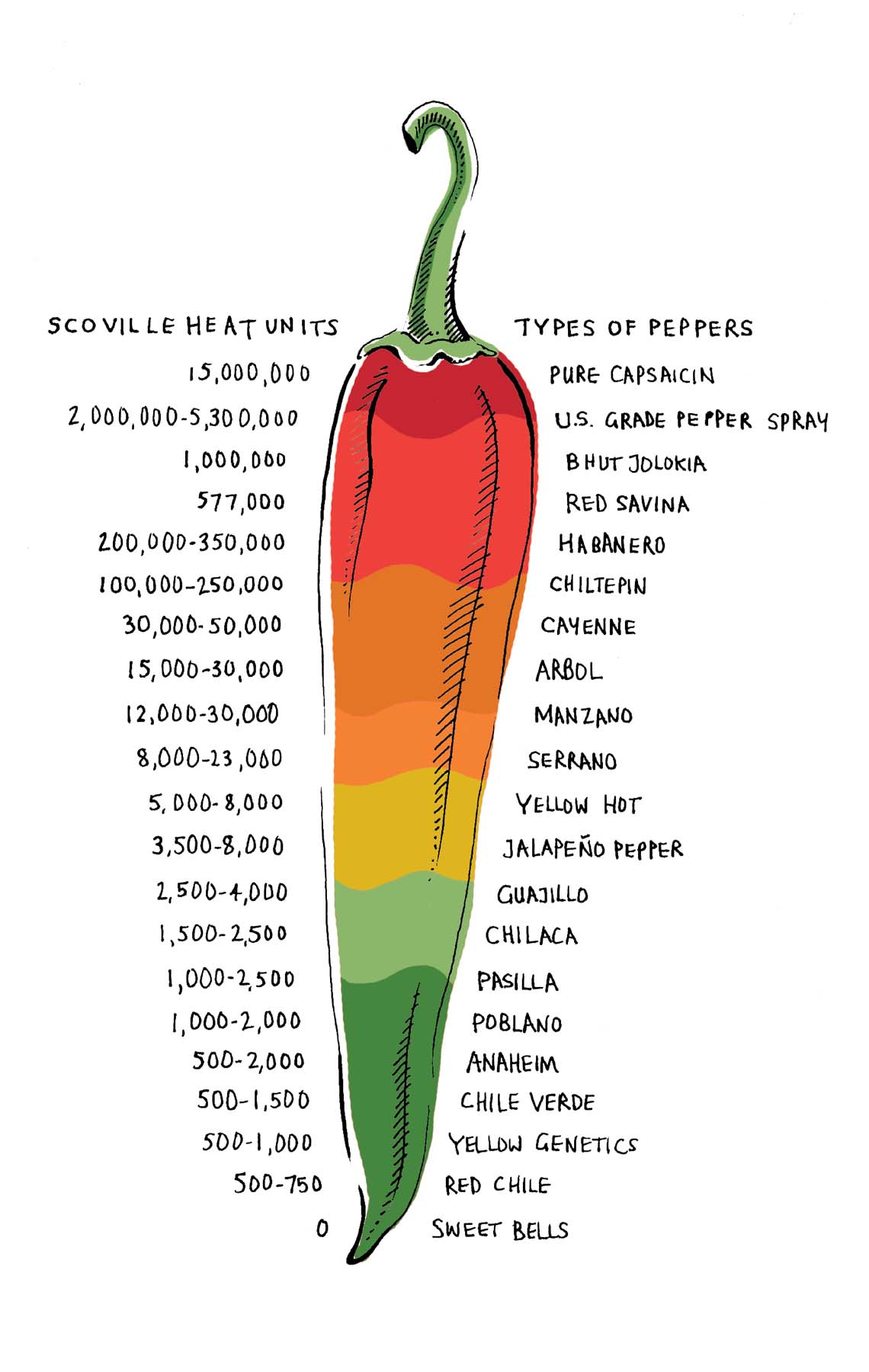

To get to the bottom of the mystery of hot sauces heat, lets first take a look at one of its most fundamental ingredients. No matter the recipe, hot sauces contain some measure of the chemical known as capsaicin. Capsaicin is found naturally occurring in chili peppers of every shape, color, or variety, all around the world. The chemical has the unique capacity of binding to a certain type of protein found in sensory neurons called the TRPV1 receptor. TRPV1 receptors are different from taste buds, in that instead of registering how a substance tastes, they detect when a substance is hot to the touch. These receptors are typically triggered by temperatures over 109 degrees Fahrenheit. Yet when brought into contact with capsaicin, the same simple chemical binding process causes them to go off in a frenzy. What the brain registers as heat from TRPV1 stimulationsay, by capsaicinis similar to what you might experience if you plucked a hot coal from the barbecue and stuck it on your tongue.

And like wrapping your mouth around a hot coal, the sudden sensation of heat can cause the body to freak out a bit. Ingesting capsaicin brings about a whole slew of ensuing physiological reactions, which, in extreme cases, are collectively referred to as a capsaicin overdose. Pores might begin to sweat, cheeks may flush, and nostrils might start to drip liberally. Saliva glands and tear ducts may start operating on overdrive. This is all part of a process called thermogenesis, whereby the body tries to purge itself of the harmful agent (when, at least in this reality, there isnt one). The bodys fight-or-flight responsean evolutionary tactic for evading dangermay also kick in, causing a rush of adrenaline and an increased heart rate. Whats more, the same TRPV1 proteins found in the oral cavity also occur all along the digestive tract, stimulating stomach cramps and increased production of fluids as the capsaicin-laced foods make their way through your insides (you can probably take a wild guess what this means).

In the midst of all this psychic and bodily turmoil, you may start to wonder what you could do to settle the body and mind in their moment of fiery crisis. Or perhaps youre thinking some variation of MAKE IT STOP. Luckily, there are certain measures one can take to dampen the effects of capsaicin and ride it out. The most intuitive solutionsloshing water around your mouthwont actually make much of a difference. In practice, it can just spread the reaction to different parts of the oral cavity, because capsaicin isnt soluble in water. Instead, reach for a glass of milk or yogurt. Oils and fats help break the chemical down, and the light acidity present in dairy products will also help neutralize the burn. Something citrusy, like lemon juice, isnt a bad idea either.

From an evolutionary standpoint, its easy to see why chili peppers came to develop capsaicin. Our reaction to the chemical is all part of the plants defensive strategy, and its a reaction shared by other species in the Mammalian class. Curiously enough, birds are seemingly unaffected by the chemical and can be found eating freely from chili plants around the world without losing their cool. The fact is, mammals digestive tracts will effectively destroy the seeds inside the chili pepper, while birds will spread them far and wide fully intact. It behooves the pepper to make nice with its skybound friends, allowing the species to be fruitful and multiply. Mammals, on the other hand, are cautioned to keep away.

THE FLAMING OF THE SHREW

Its been commonly accepted that humans are unique among mammals in tolerating spicy, capsaicin-rich foods. But researchers at the Kunming Institute in Yunnan, China, have recently discovered a surprising thing about the tree shrew. They determined that the tree shrews favorite food is a capsaicinoid-rich pepper plant called the Piper boehmeriaefolium. In order to study this further, scientists invented a kind of special-made treat for the little guys by adding the peppers capsaicinoids to some corn pellets. The tree shrews eagerly snacked on the pellets, while mice stayed away. Whats more, the shrews showed an increased preference for the corn snacks as the scientists jacked up the capsaicinoid content.

So whats their secret? It turns out that shrews dont actually get the same enjoyment out of heat-seeking as humans do. Rather, they benefit from a decreased sensitivity to capsaicin altogether. This is due to a mutation in their TRPV1 receptors, allowing them to freely nibble on the pepper plants without feeling much of anything.