mindfulness skills

for trauma and ptsd

PRACTICES FOR RECOVERY AND RESILIENCE

Rachel Goldsmith Turow

W.W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publishers Since 1923

New York London

To Jon, Oriana, and Felix

mindfulness skills

for trauma and ptsd

Copyright 2017 by Rachel Goldsmith Turow

Important Note:Mindfulness Skills for Trauma and PTSD is intended to provide general information on the subject of health and well-being; it is not a substitute for medical or psychological treatment and may not be relied upon for purposes of diagnosing or treating any illness. Please seek out the care of a professional healthcare provider if you are pregnant, nursing, or experiencing symptoms of any potentially serious condition.

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to

Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at

special sales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Vicki Fischman

Production manager: Christine Critelli

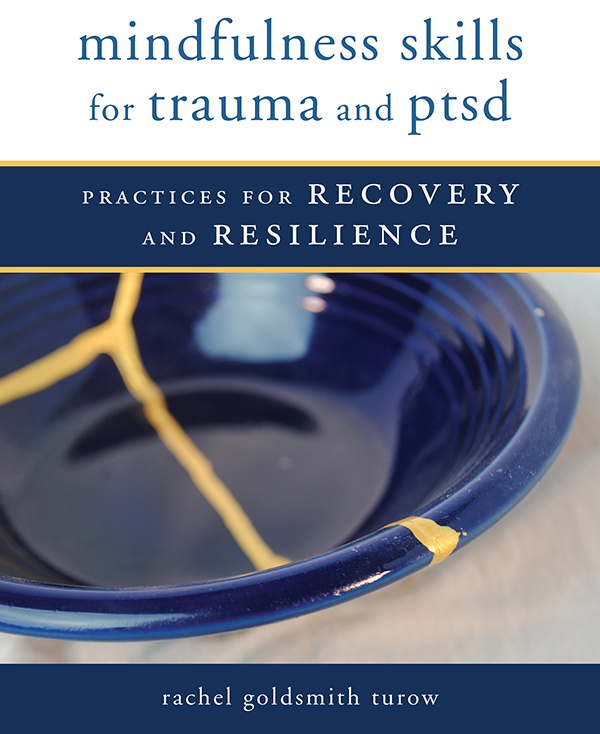

Jacket design by Lauren Graessle | Jacket photo by Paul Pustelnik, Kintsugi Gifts Inc., KintsugiGifts.com |

Author photo Monica Lloyd/Seattle

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Turow, Rachel Goldsmith, author.

Title: Mindfulness skills for trauma and PTSD : practices for

recovery and resilience / Rachel Goldsmith Turow.

Description: First edition. | New York : W. W Norton & Company, [2017] |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016029070 | ISBN 9780393711264 (pbk.)

Subjects: | MESH: Trauma and Stressor Related Disorderstherapy | Mindfulnessmethods

Classification: LCC RC552.T7 | NLM WM 172.5 | DDC 616.85/21dc23 LC

record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016029070

ISBN 978-0-393-71127-1 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D, 3BS

contents

S EVERAL YEARS AGO , I helped facilitate a mindfulness class for Veterans that took place in a room surrounded by busy corridors on all sides. We practiced a variety of mindfulness exercises, including paying attention to our breathing and using the body scan approach to observe sensations from head to toe. Many of the participants described frustration or anger at the sounds that people made as they passed by, especially directed toward a particular unseen person wearing shoes that produced a sharp click-clack-click against the floor. The sounds seemed to interfere with what participants were supposed to be concentrating onthe practice of mindfulness. Our practice emphasized noticing our thoughts and reactions, without judging our experience, while returning our attention over and over again to our chosen point of focus.

After a few weeks, the participants discovered that their reactions to the sounds of people passing had shifted. The same people who had expressed anger at the sound of loud shoes noticed that they were no longer bothered by them. Something had changed. The sounds of people passing by remained consistent, so the change must have occurred within the perceiver. The Veterans described surprise, awe, and gratitude at this change, which came about through their paying attention in a nonjudgmental way to their own experiences when hearing the loud shoes, over and over, rather than pushing away or ignoring their reactions. Their process reminded me of my own evolving responsesdistraction, changing to annoyance, then acceptance, and finally intense fondnessto the ding! of the elevator outside the room in the community center where I first practiced meditation. What had seemed like a problem or obstacle turned out to be a vehicle for managing feelings using mindfulness practice; a marker of internal movement; and a sign of hope that other thoughts and emotions could transform in the same way.

Trauma impacts our lives on multiple levelsour thoughts, emotions, physical health, relationships, and our overall ability to function. People can and do recover from trauma to lead healthy, fulfilling lives, and there are many ways to heal. With practice, we can acknowledge the truth of our trauma while also developing new life skills and perspectives. Mindfulness and self-compassion can help us tolerate and reduce distress, decrease self-criticism, build kindness towards ourselves and others, clarify feelings, direct attention, make wise choices, and promote bodily relaxationall of which can reduce trauma symptoms and improve our overall well-being.

Practicing the small stuff can help with the big stuff. We can begin by attending with care and interest to present-moment sensations of walking or breathing, experiences that are usually not as highly charged as our trauma. Whereas trauma often leaves us feeling helpless, our mindfulness practice can empower us. We get to choose the exercises that feel best, and determine how to handle our experiences moment by moment. We can also titrate our exposure to painful materialthat is, continuously adjust how much we address deliberately at any given time. By practicing new skills over and over, we create changes in our thinking, emotions, and brain systems that can assist us in handling past trauma, as well as current and future challenges.

The conventions of lifeas well as many traumatic environments themselvescan push us to hide our trauma and our related thoughts and feelings. Most of us do not want to sob on the bus or during a business meeting, and we certainly do not have to share every aspect of our experience with others in order to be authentic. However, we can become caught in the other extremefeeling pressure to pretend that things are fine when they are not. In his story The Lady with the Little Dog, the writer Anton Chekhov (2000) describes a character who is leading

two lives, an apparent one, seen and known by all who needed it, filled with conventional truth and conventional deceit, which perfectly resembled the lives of his acquaintances and friends, and another that went on in secret. And by some strange coincidence, perhaps an accidental one, everything that he found important, interesting, necessary, in which he was sincere and did not deceive himself, which constituted the core of his life, occurred in secret from others. (p. 374)

In addition to concealing our feelings from others, as Chekhov illustrates, we often keep parts of our emotional lives hidden even from ourselves.

To make positive changes, we usually need to pay attention to what is truly happening, rather than to how we are supposed to feel or act. This attention can occur when we are on our own, or in the company of supportive friends, family, or health professionals. In a world that often does not acknowledge trauma and its effects, I have found the spaces that emphasize the reality of our experiencessuch as meditation rooms, therapy offices, and many books and relationshipsto be extremely comforting. Even though each context can contain imperfections, I appreciate the focus on what is really happening, rather than on image or pretense. I wish for everyone who wants it the space, time, and compassion to provide kind attention to their actual experiences.

This book approaches trauma and recovery as universal themes not confined to a specific problem and population, even as it recognizes the meaningful differences among trauma types and trauma responses. It treats the challenge of how to manage our minds effectively as a central task of being human, rather than as an individual problem or a necessity only for those of us with mental health difficulties. As a research scientist, educator, and psychotherapist, I aim to provide information that is grounded in scientific evidence. I have incorporated research studies throughout the book that can illuminate processes of trauma adaptations, trauma recovery, and resilience. The book also notes a range of frameworks and strategies offered by mindfulness teachers. Many of the skills and perspectives that they describe have generated robust scientific evidence demonstrating their accuracy and effectiveness. I have also included In Their Own Words sectionsfirst-person accounts of experiences with trauma, mindfulness, and self-compassion. These stories were submitted by friends and colleagues, rather than by my own patients or students, and all of the contributors provided permission for their experiences to be included anonymously.

Next page