The Myth of the Missing Black Father

The Myth of the

Missing Black Father

EDITED BY Roberta L. Coles and Charles Green

Columbia University Press New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2010 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-52086-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The myth of the missing black father / edited by Roberta L. Coles and Charles Green.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-14352-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-231-14353-0

(pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-231-52086-7 (e-book)

1. African American fathers. 2. Absentee fathers. 3. African American families. I. Coles,

Roberta L. II. Green, Charles (Charles St. Clair) III. Title.

HQ 756. M 98 2010

306.874'208996073dc22

2009019270

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

References to Internet Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

This book is dedicated to all committed black fathers and their children living in the United States and around the globe.

Contents

Most books, beginning with research and continuing through the writing stage, require at least a couple years of preparation before they appear in print. Edited volumes, particularly those for which chapters have been specifically prepared by the contributors, can be that much more challenging. Thus, in the process of coordinating and organizing this book project the need for outside resources and special assistance was ever more demanding. While the benefits of the computer and information age were extremely helpful in communicating with contributors who were spread across several states, there was still the need for other support in the form of funding for research-related costs, such as research assistants, travel, and supplies, to mention a few. For this, we are indebted to our academic institutionsMarquette University and Hunter College of the City University of New Yorkfor approving small research grants: specifically, from Marquette University, the Regular Research Grant and the Summer Faculty Fellowship, and from Hunter College, the Professional Staff CongressCUNY Award Program.

In addition to funding sources, there are number of colleagues as well as sociology students and personal contacts whom we would like to thank for their support in the areas of technical consultation, referral of subjects for the interviews, and their unearthing of journal articles, newspaper clippings, Web sites, and other relevant research information on the topic of black fatherhood that we might otherwise have overlooked. Our gratitude goes out to Ted Anderson, Marie Lesly Auguste, Dawn Bonnett, Erica Chito-Childs, Claire Green, Marguerite Holm, Tammy Jones, Naomi Kroeger, Dominic Lewis, Tina Mangum, Felicia Martin, Janina McCormack, James Mitchell, Joong-Hwan Oh, Sandy Ramer, Ruth Sidel, Naseive Smith, Janice Staral, the George Sanders Fathers Resource Center, Mieko Manuel-Timmons, and Basil Wilson.

Our gratitude is extended to the anonymous reviewers for their favorable support, to editors at Columbia University PressLauren Dockett, Avni Majithia, and Michael Haskellfor their help at all stages in preparing the manuscript, and to the contributors to this volume, who persisted through multiple revisions. And, finally, we are indebted to the many father-respondents for telling stories that bring insight into fathering.

The black male. A demographic. A sociological construct. A media caricature. A crime statistic. Aside from rage or lust, he is seldom seen as an emotionally embodied person. Rarely a father. Indeed, if one judged by popular and academic coverage, one might think the term black fatherhood an oxymoron. In their parenting role, African American men are viewed as verbs but not nouns; that is, it is frequently assumed that Black men father children but seldom are fathers. Instead, as the law professor Dorothy Roberts (1998) suggests in her article The Absent Black Father, black men have become the symbol of fatherlessness. Consequently, they are rarely depicted as deeply embedded within and essential to their families of procreation. This stereotype is so pervasive that when black men are seen parenting, as Mark Anthony Neal (2005) has personally observed in his memoir, they are virtually offered a Nobel Prize .

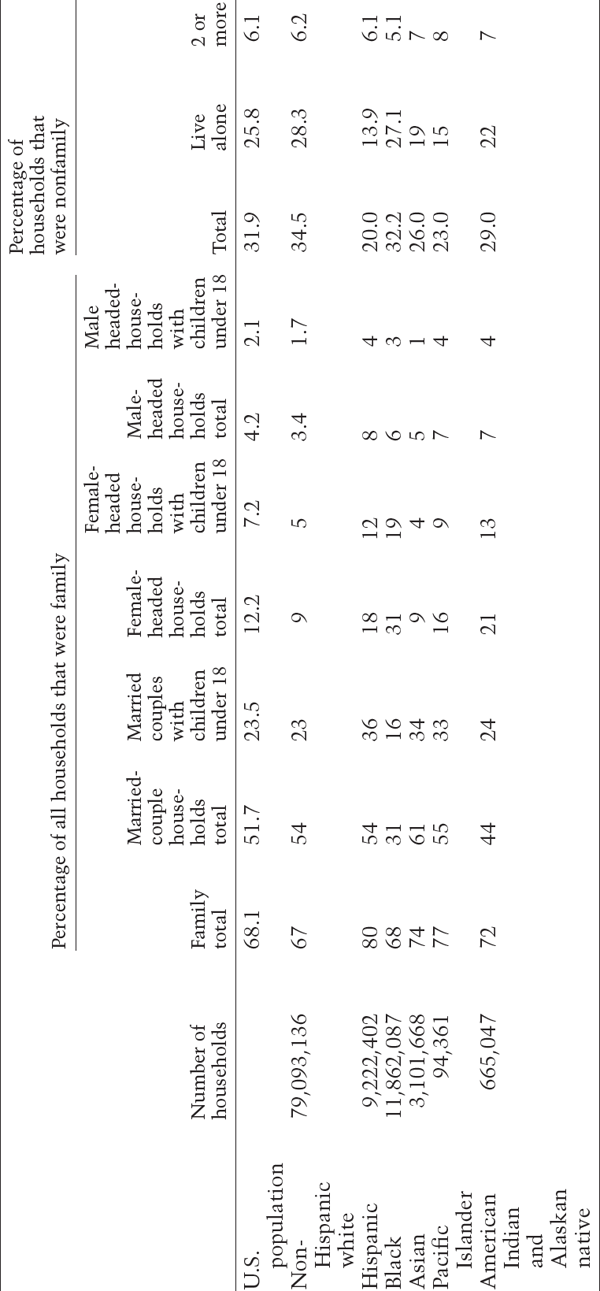

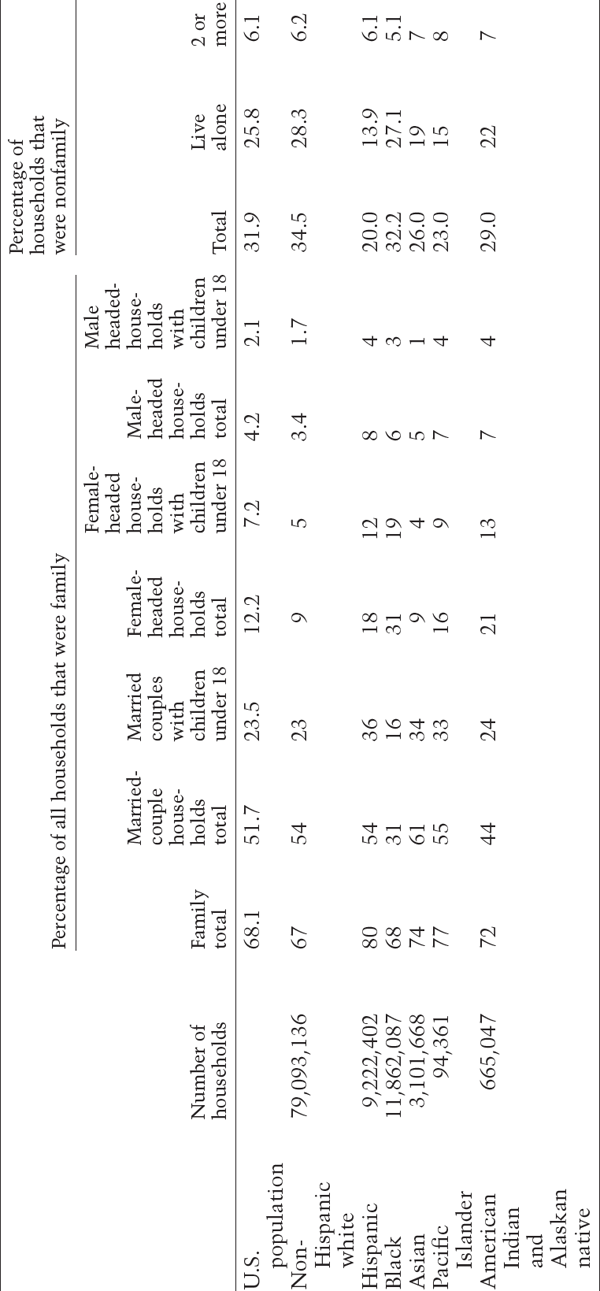

But this stereotype did not arise from thin air. As shown in , over 50 percent of African American children lived in mother-only households in 2004, again the highest of all racial groups. Although African American teens experienced the largest decline in births of all racial groups in the 1990s, still in 2000, 68 percent of all births to African American women were nonmarital, suggesting the pattern of single-mother parenting may be sustained for some time into the future (Martin et al. 2003). This statistic could easily lead observers to assume that the fathers are absent.

Family and Non-Family Households Total and by Race, 2000

Source: U.S. Department of Commerce (2000), Quick Table-P10, Matrices PCT8, PCT17, PCT18, PCT26, PCT27, and PCT28.

Living Arrangements of Black Children, 2004

| Living arrangements | Black children |

| Two parents | 37.6% |

| Married | 33.9 |

| Unmarried | 3.7 |

| Mother-only | 50.4 |

| Father-only | 3.3 |

| Neither parent | 8.8 |

Source: Kreider (2008).

While it would be remiss to argue that there are not many absent black fathers, absence is only one slice of the fatherhood pie and a smaller slice than is normally thought. The problem with absence, as is fairly well established now, is that its an ill defined pejorative concept usually denoting nonresidence with the child, and it is sometimes assumed in cases where there is no legal marriage to the mother. More importantly, absence connotes invisibility and noninvolvement, which further investigation has proven to be exaggerated (as will be discussed below). Furthermore, statistics on childrens living arrangements () also indicate that nearly 41 percent of black children live with their fathers, either in a married or cohabiting couple household or with a single dad.

These African American family-structure trends are reflections of large-scale societal trendshistorical, economic, and demographicthat have affected all American families over the past centuries. Transformations of the American society from an agricultural to an industrial economy and, more recently, from an industrial to a service economy entailed adjustments in the timing of marriage, family structure, and the dynamics of family life. The transition from an industrial to a service economy has been accompanied by a movement of jobs out of cities; a decline in real wages for men; increased labor-force participation for women; a decline in fertility; postponement of marriage; and increases in divorce, nonmarital births, and single-parent and non-family households.

These historical transformations of American society also led to changes in the expected and idealized roles of family members. According to Lamb (1986), during the agricultural era, fathers were expected to be the moral teachers; during industrialization, breadwinners and sex-role models; and during the service economy, nurturers. It is doubtful that these idealized roles were as discrete as implied. In fact, LaRossas (1997) history of the first half of the 1900s reveals that public calls for nurturing, involved fathers existed before the modern era. It is likely that many men had trouble fulfilling these idealized roles despite the legal buttress of patriarchy, but it was surely difficult for African American men to fulfill these roles in the context of slavery, segregation, and, even today, more modern forms of discrimination. A comparison of the socioeconomic status of black and white fathers illustrates some of the disadvantages black fathers must surmount to fulfill fathering expectations. According to Hernandez and Brandon (2002), in 1999 only 33.4 percent of black fathers had attained at least a college education, compared to 68.5 percent of white fathers. In 1998, 25.5 percent of black fathers were un- or underemployed, while 17.4 percent of white fathers fell into that category. Nearly 23 percent of black fathers income was half of the poverty threshold, while 15 percent of white fathers had incomes that low.

Next page