Contents

Guide

Page List

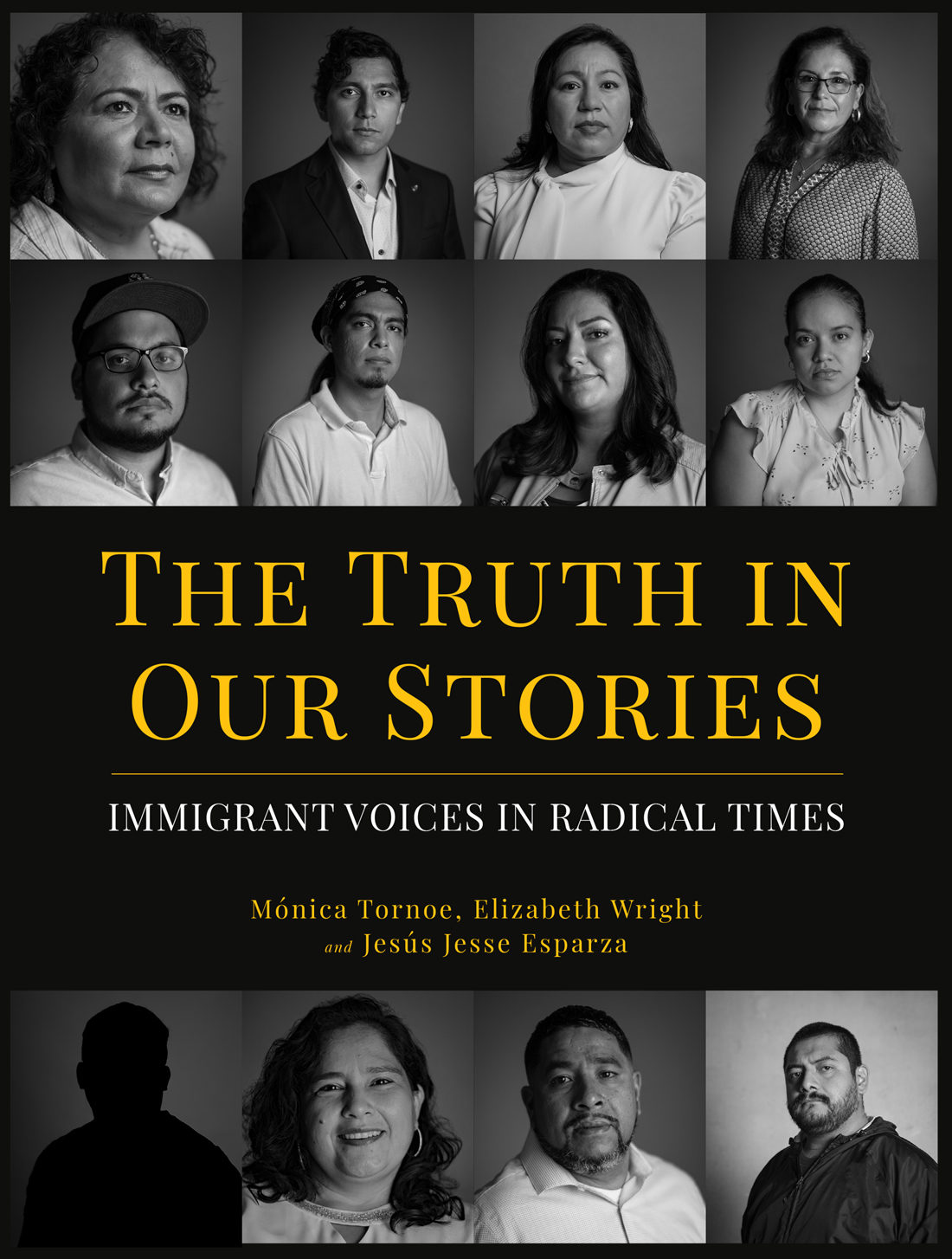

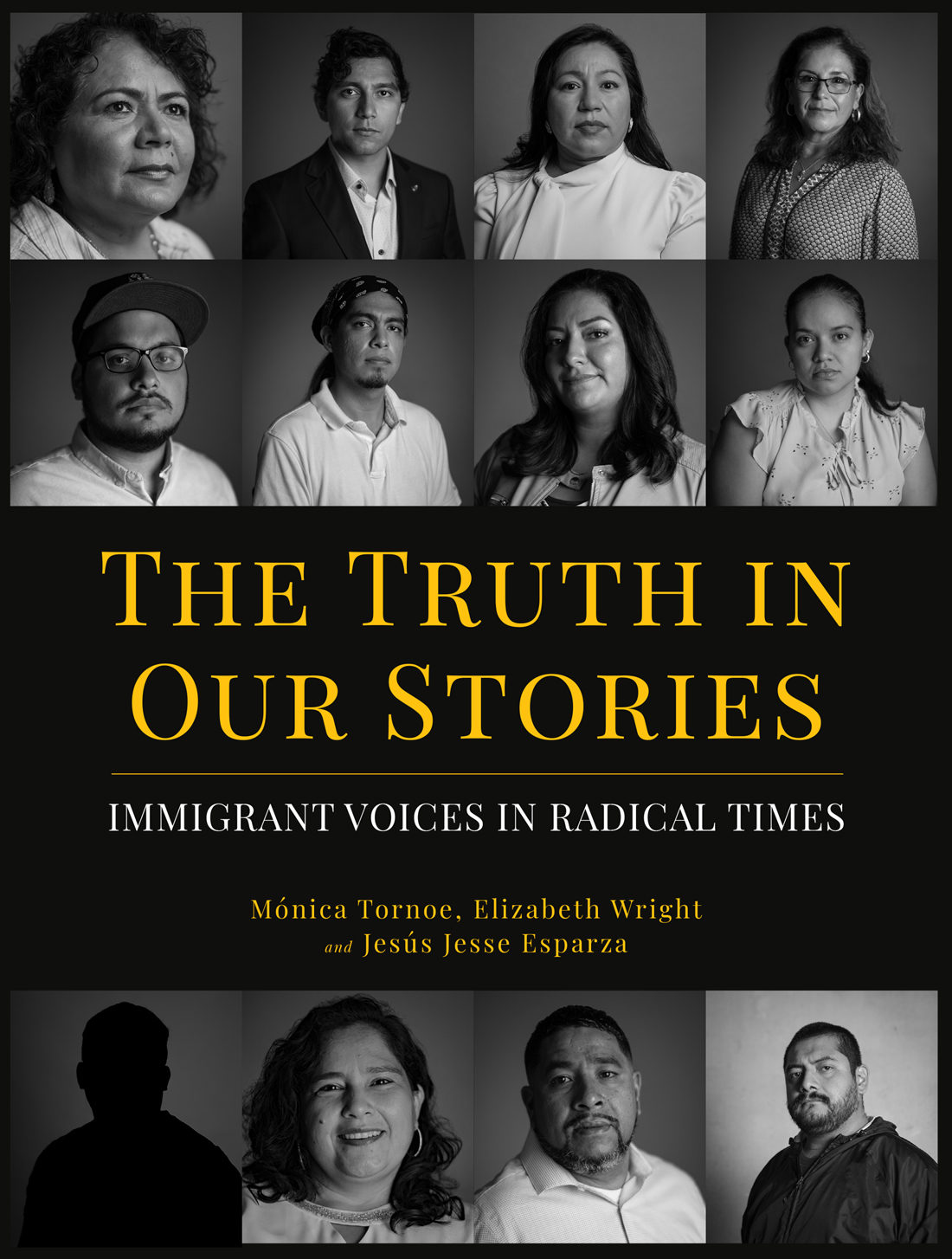

THE TRUTH IN OUR STORIES

THE TRUTH IN OUR STORIES

THE TRUTH IN OUR STORIES

IMMIGRANT VOICES IN RADICAL TIMES

Edited by Mnica Tornoe, Elizabeth Wright, and Jess Jesse Esparza

IZZARD INK PUBLISHING

PO Box 522251

Salt Lake City, Utah 84152

www.izzardink.com

Copyright 2022 by Mnica Tornoe / Undocumented Stories

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, electronically or otherwise, or by use of a technology or retrieval system now known or to be invented, without the prior written permission of the author and publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tornoe, Mnica, editor. | Wright, Elizabeth R. (Reverend), editor. | Esparza, Jess Jesse, editor.

Title: The truth in our stories : immigrant voices in radical times / edited by Mnica Tornoe, Elizabeth Wright, and Jess Jesse Esparza.

Other titles: Immigrant voices in radical times

Description: First edition. | Salt Lake City, Utah : Izzard Ink Publishing, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022002892 (print) | LCCN 2022002893 (ebook) | ISBN 9781642280791 (paperback) | ISBN 9781642280807 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Hispanic AmericansBiography. | Hispanic AmericansSocial conditions. | ImmigrantsUnited StatesSocial conditions.

Classification: LCC E184.S75 T79 2022 (print) | LCC E184.S75 (ebook) | DDC 305.868/073dc23/eng/20220126

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022002892

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022002893

Designed by Daniel Lagin

Cover Design by Andrea Ho

Photography by Joshua and Samuel Gandara

First Edition

Contact the author at

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-64228-079-1

eBook ISBN: 978-1-64228-080-7

Dedicated to all who hunger and thirst for justice... you shall be satisfied.

The propagandists purpose is to make one set of people forget that certain other sets of people are human.

ALDOUS HUXLEY

The shortest distance between truth and a human being is a story.

ANTHONY DE MELLO

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

With utmost sincerity, we wish to express our eternal gratitude to the brave women and men who contributed to this project as storytellers. This manuscript would not exist without their participation; thank you. We wish to acknowledge also the support from our respective institutions: Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary; Justice for Our Neighbors, Austin Region; and Texas Southern University. We also wish to acknowledge that this project is supported by funding from the Institute for Diversity and Civic Life, made possible by a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation. To the team at Izzard Ink Publishing, we thank you for ensuring that all the necessary edits to the manuscript were done correctly and on time; the input was invaluable. To our amazing photographers, Joshua and Samuel Gandara from Cromatica, and to Mel Hummel, mil gracias for the work you all did. Special thanks to Melissa Wiginton for her support. Lastly, to all the individuals who allowed us to speak with them, and to the many others who contributed in different ways to the completion of this project, we thank you as well. Without your support, this project remains in its infancy.

INTRODUCTION

I n an age of disinformation and growing racism, misconceptions about immigrants coupled with anti-immigrant sentiment have spread throughout American society. Consequently, the country has seen a concerning uptick in anti-immigrant rhetoric, harsh policies, and paramilitary activities; all of which threaten immigrant communities.

For more than a century, increases in immigration have been followed by a rise in nativism and resentment. After the war against Mexico in 1848, Mexican Americans found themselves in a rapidly changing world as the entire region west of the Mississippi River underwent a tremendous amount of transformation, resulting in their displacement, disenfranchisement, segregation, and exploitation. While the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo concluded the war between Mexico and the United States and established Mexican Americans as citizens of the US, the perception among those moving into the newly acquired territories was that they were foreigners who did not belong.

The turn of the twentieth century brought new industries such as the railroad, petroleum, and automobiles. Mexican immigrants, in search of work opportunities in these new trades, arrived in the US in record numbers, triggering a massive wave of nativism and anti-immigrant sentiment. The prevailing thought of the period among nativists was that immigrants were dirty, disease-carrying, dangerous foreigners with a predisposition for criminal behavior who competed against American-born workers for jobs. Additionally, they viewed immigrants, men particularly, as hypersexual, with lustful designs on white women. Certainly, they saw immigrants as biologically inferior, given their miscegenated racial make-up. Adding fuel to the fire was the fact that many immigrants spoke Spanish, and in a country where speaking a language other than English was unacceptable, this only exacerbated the entrenched anti-immigrant sentiment.

When the revolution broke out in Mexico in 1910, millions more immigrants, displaced by war, entered the US, sparking another wave of nativism. Many nativists believed immigrants to be radicals, espousing revolutionary sentiment toward the US government. Others labeled them anarchists and pointed to groups such as El Partido Liberal Mexicano, a revolutionary group that gained a foothold in the US in 1905 to support their positions against immigrants.

During the 1920s, the nation saw the return of the Ku Klux Klan, the oldest domestic terrorist organization in the US. Part of its platform was a determination to expel all undesirables, including immigrants. Additionally, the nation saw the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924, which limited the number of people who could legally immigrate to the United States to 2 percent of each nationalitys 1890 population each year. Known as quotas, this policy applied to all nations; however, the rate of allowable immigrant entrants was not equally applied. Countries with large Spanish-speaking, Catholic, Jewish, Islamic, and Asian populations had fewer application opportunities than their English-speaking, protestant counterparts. The Immigration Act of 1924 also officially created the US Border Patrol, the leading agency in militarizing the southern border.

As the twenties pushed onward, nativists relied heavily on junk science to defend their opposition to immigrants and immigration. Known as the eugenics movement, its proponents argued that immigrants, Mexicans in particular, would negatively influence American society given their alleged biological inferiority. It further claimed that immigrants brought disease, crime, and poverty to the US by depressing wages and displacing American-born workers. Emerging from this racist science were several forms of punitive legislation targeting immigrants, including the Box Bill, a law introduced in 1926 that tried to bar immigration from all of Latin America. Nicknamed after John C. Box, a politician and bona fide eugenicist out of Texas, the legislation addressed the so-called Mexican Problem, that is, the problem of how to handle all the immigrants in the country. According to Box and other nativists, one solution was to remove immigrants from the country, but that was often too expensive and required massive labor. The easier fix was segregating them to the fields, as a separate labor force, thereby keeping them away from mainstream society.