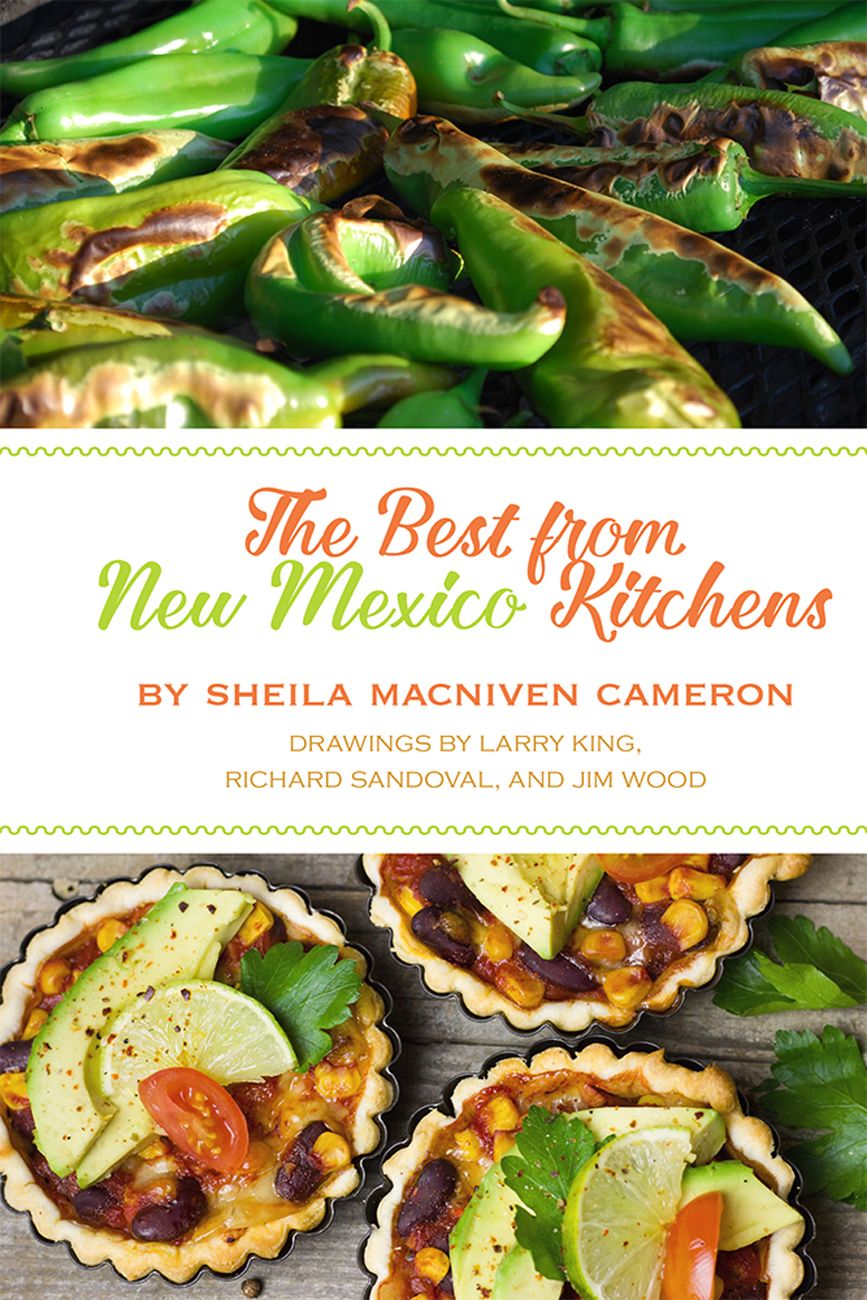

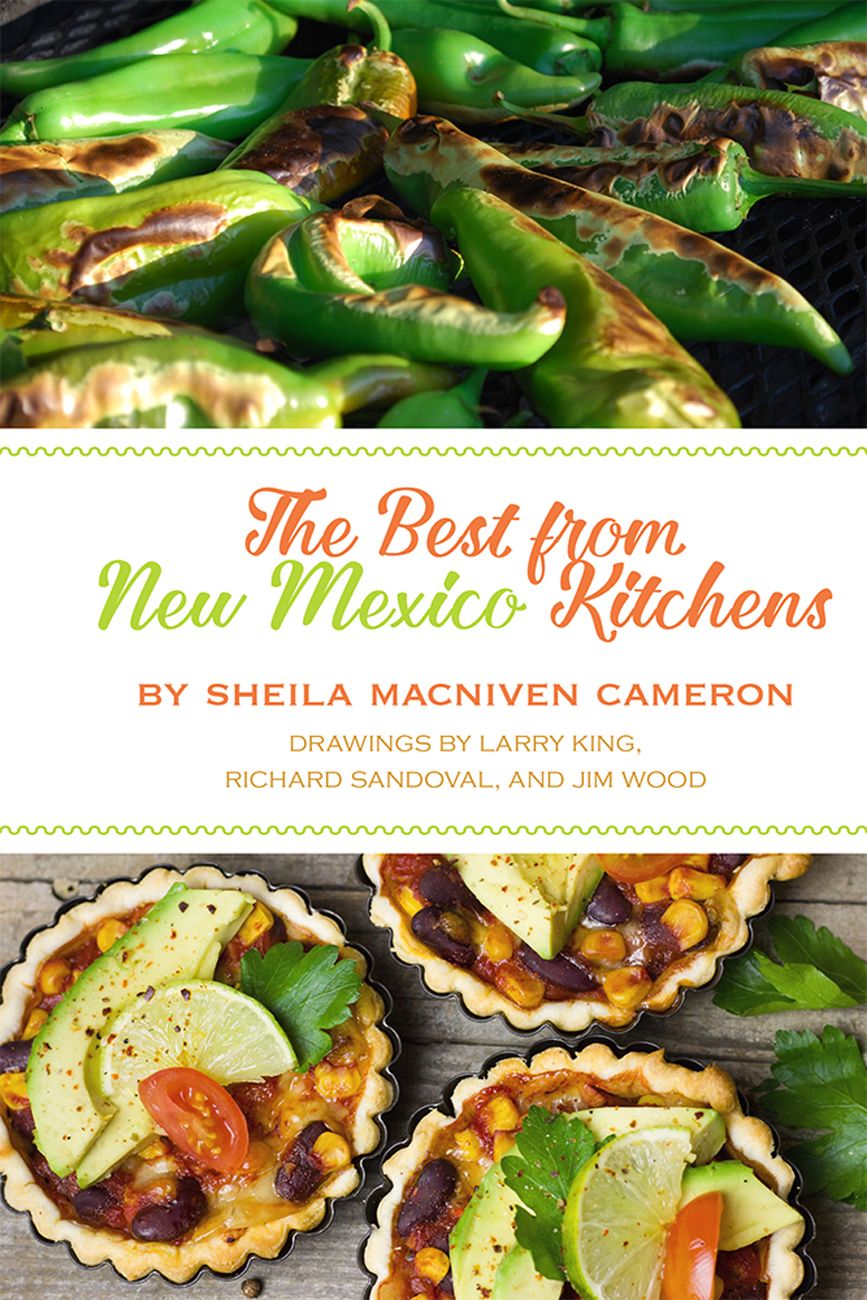

The Best from New Mexico Kitchens The Best from

The Best from New Mexico Kitchens The Best from

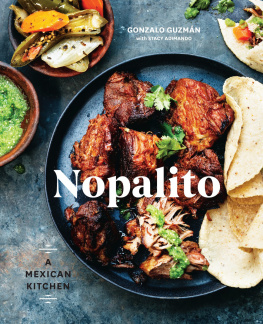

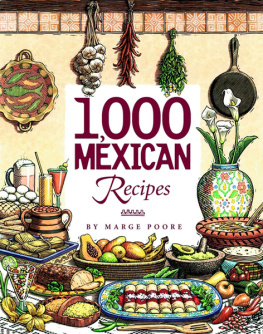

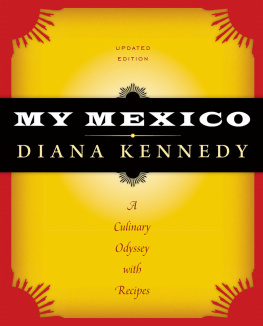

New Mexico Kitchens Sheila MacNiven CameronDrawings by Larry King, Richard Sandoval, and Jim Wood University of New Mexico Press Albuquerque 1978 by New Mexico Magazine University of New Mexico Press edition published 2017 by arrangement with New Mexico Magazine All rights reserved. Reproduction of the contents in any form, either in whole or in part, is strictly prohibited without written permission of the publisher, except for brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Cameron, Sheila MacNiven, editor. Title: The Best from New Mexico Kitchens / [edited by] Sheila MacNiven Cameron ; drawings by Larry King, Richard Sandoval, and Jim Wood. Other titles: New Mexico magazines The Best from New Mexico Kitchens. | New edition of: New Mexico Magazines The Best from New Mexico Kitchens. 1978. | Includes index. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017022068| ISBN 9780826359582 (spiral : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780826359599 (e-book) Subjects: LCSH: CookingNew Mexico. | Cooking, AmericanSouthwestern style. | LCGFT: Cookbooks. Classification: LCC TX715 .N52378 2017 | DDC 641.59789dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017022068 Cover illustration: Bernadette Wurzinger CONTENTS  INTRODUCTION There are those who call it Mexican cooking. But its not the same as the cooking south of the border.

INTRODUCTION There are those who call it Mexican cooking. But its not the same as the cooking south of the border.

Or east or west of the border, either. New Mexican cooking is unique to New Mexico. The stacked enchiladas topped with an egg and smothered in thick red sauce, the tender sopaipillas, the posole stew, rich and meaty, the green chile and blue corn tortillasthese are typically New Mexican dishes. Most Mexican cooking is essentially Indian, as adapted by the Spanish. In New Mexico, the cooking therefore was originally based on Pueblo Indian dishes and on the foods grown by these peopleand not on the foods prepared by the Indians of Mexico. But it was more than that, of course.

As time went on, there were influences from Mexico, from France, from Britain, from the Eastern Seaboard colonies. The cowboy and the trader contributed to the cuisine as did the railroader, the artist and the scientist. And today, New Mexico kitchens, in typical Southwestern fashion, turn out a rich variety of dishesfrom chuckwagon specialties to haute cuisine. But always there is that special dash, that New Mexican fillip that turns a commonplace dish into the sensational. Green chile in green pea soup. Fresh corn in a quiche.

Red chile powder in a Yorkshire pudding. Cheese in a bread pudding. A number of the recipes in this book have appeared in past issues of New Mexico Magazine, but many others have never before been in print. Some come from the kitchens of New Mexico restaurants. Most, however, come from home kitchens, where good cooks daily turn out those tasty, economical and healthful dishes that make the taste buds tingle and leave the appetite unsatisfied with lesser offerings.  CHILE

CHILE

NEW MEXICOS

FIERY SOUL by John Crenshaw T o my knowledge, no one has ever died from an overdose of 8-Methyl-N-vanillyl-6-nonenamide, although countless thousands have known the symptoms of gastronomic flashbacks.

The substance may be addictive; although there are no severe withdrawal symptoms, its prolonged absence leaves regular users with a vague, empty feeling located nearer the soul than other, more definable areas of the physical body. The substance, become more symbolic than curative, stirs memories and longing: old friends and red wine, close families at dinner, fields of deep green wetted by the Rio Grandes muddy waters. Simply put, its homesickness, a yearning focused on a particular chemical that for many is a way of life. The sufferer is likely a displaced New Mexican, victim of the Capsaicin Withdrawal Blues. No one of them would tell you hes aching for a taste of home and 8-Methyl-N-vanillyl-6-nonenamide or even for a dash of capsaicin, the name given that unwieldy chemical designation. They would tell you, instead, that they have found not one, not one decent restaurant anywhere in town (this could be in a city of millions), that they cant find an enchilada anywhere, that if they ask for chile they get a red, soupy concoction of meat and something, that the best taco stand around offers Tabasco for a sauce.

And its chile they want green chile, or red chile, but chile. The pod, not the soup. Chile with flavor, not just heat. New Mexico chile. Capsaicin, or an isomer thereof, is that oily, orangish acid layered along the seeds and veins of the chile pod, one of New Mexicos officially adopted state symbols. Capsaicin, then, makes chile chile, gives it the piquancy ranging from innocuous to incendiary, brings tears to the eaters eyes, blisters to his lips, fire to his belly and joy to his heart.

Chile: Spicy, flavorful, unique indeed a symbol specific to the heart of the Southwest and a fitting catalyst for that ancient disease of the displaced. Chile: Ancient, honored, symbolic. A spice and a fruit unto itself. A demigod and a symbol, the center of controversy of national combat. Chile: More acres of it grow in New Mexico than all the other states put together. Chile: Although New Mexicans consume more per capita than do any others of the United States and have adopted it as an official symbol, we are not the first to honor it.

The Aztecs accorded chile the status of a minor god a war god and tempered adoration with fear of the flamboyant fire contained in our present crops ancestors. Known to the Aztecs as Chili and Axi (chile is the Spanish and favored spelling in New Mexico), the chile and its ire were cooled by culinary marriage to tomatl, the tomato. It was a marriage of cousins, but one that worked to the advantage of each of these noble families. (Chile is also cousin to the potato, another New World gift, and to the eggplant. Green chile chopped into and fried with diced potatoes is a hearty breakfast side dish and another fine marriage of cousins. And green chile wed to the tomato and comforting the eggplant gives the eggplant parmesan a whole New World flavor.) Popularity is, of course, reason enough for increasing demand, and along with interest shown by the New York Times, Esquire ran an interview with an anonymous (good thing for him) person who claimed to be creator of the worlds greatest chile.

With cheek, he promotes a concoction that combines, with twelve pounds of cubed brisket, as much oregano, and as much cumin, as chile powder not to mention gobs, dashes and spoonfuls of cayenne, Dijon mustard, lime and lemon juice, sugar (sugar?), woodruff (woodruff??), garlic, gumbo file, chicken fat, beer, and Tabasco and Worcestershire sauce, for crying out loud. One wonders what color the mess might be. Still, the word is spreading, and the International Connoisseurs of Green and Red Chiles membership list shows that its not just the Spaniards descendants who tang their tongues with New Mexicos best. The chile didnt originate here (although its more sublime developments took place along the New Mexican Rio Grande); anthropologists digging in South America have dated plant remains to 700 B.C. Those pods must have been incredibly hot, if age is a yardstick and later Aztec crops were believed to be gods of war. But it is old even here; Spanish expeditions of the late 1500s reported New Mexicos Puebloans growing it and producing a (relatively) milder variant that could be eaten without addition of tomatoes or eggplant.

Next page

The Best from New Mexico Kitchens The Best from

The Best from New Mexico Kitchens The Best from INTRODUCTION There are those who call it Mexican cooking. But its not the same as the cooking south of the border.

INTRODUCTION There are those who call it Mexican cooking. But its not the same as the cooking south of the border. CHILE

CHILE