William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

HarperCollinsPublishers

1st Floor, Watermarque Building, Ringsend Road

Dublin 4, Ireland

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2022

Copyright Duncan Minshull 2022

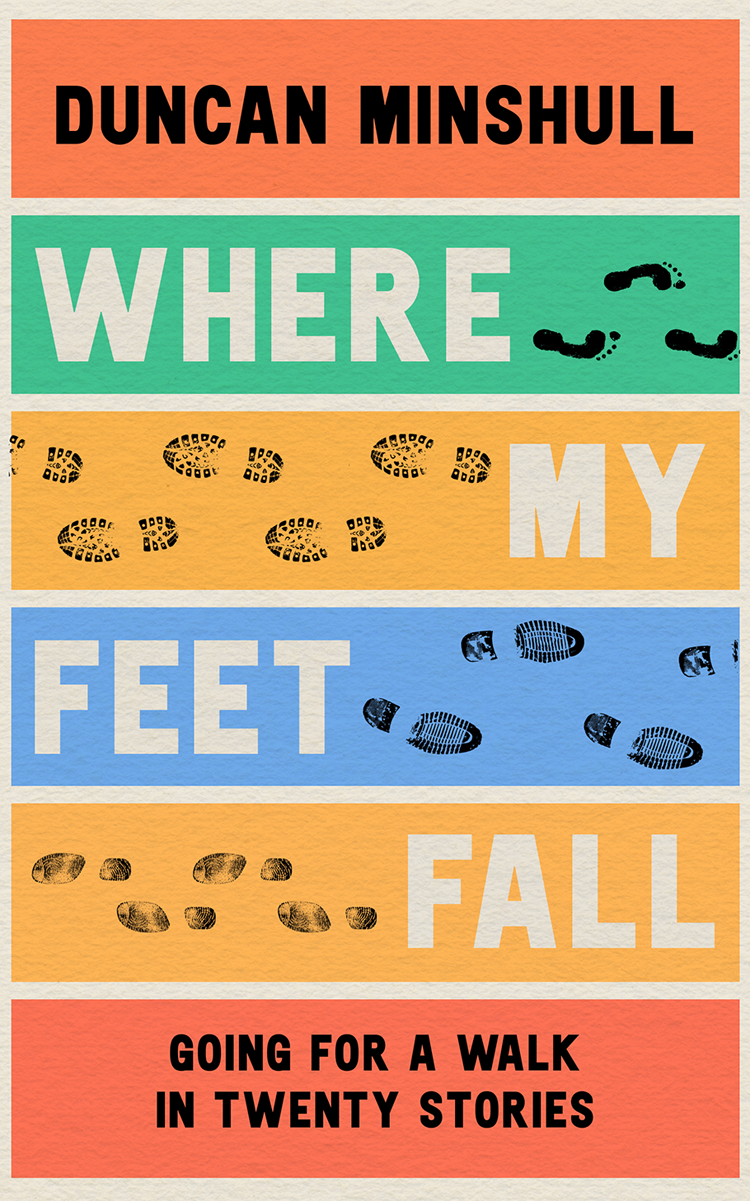

Cover design by Jo Thomson, footprints Shutterstock

Duncan Minshull asserts the moral right to be identified as the editor of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008414115

Ebook Edition March 2022 ISBN: 9780008414122

Version: 2022-01-26

In memory of my walking mother,

June Minshull, 19312021

Before you follow these wonderful wanderers across the pages of Where My Feet Fall, a bit of backtracking first to April 1336. To the day Petrarch the poet climbed the craggy side of Mont Ventoux in southern France, in air fine, and had much to say about it about fellow travellers, about the terrain covered, about getting high and gazing afar. His was an early pedestrian story roundly written. It examined the reasons for going on foot and noted the good things gained. It paved a way.

It would pave a way to the English Romantics (William Coleridge, the Wordsworths), who used prose as well as poetry to describe moving into nature, and sublimely so. Another, William Hazlitt, went walking to consider the act of walking itself, and in a popular essay told us to venture alone because our friends talk a lot and block the views. After them came the Victorians and Edwardians, acute responders to their own pedestrian heydays, who didnt link it only to necessity (poverty) or recreation (affluence). They talked of roaming urban and indeterminate places and were attuned to a mental aspect. Charles Dickens declared he might explode and perish should he not leave the house every dawn, every dusk. Virginia Woolf said likewise on one of her night walks.

And if the backtracking was to end and we look to more recent times? There has always been a need for air and exercise, for the sights and sounds and aromas, for the hours to slow and the world to reveal. But dont our walks have added intent? More and more we move through nature to address environmental concerns, and to rightfully roam. We move through cities to search and to clarify (were all psychogeographers now), and to happily snub the wheel. We move everywhere to settle the mind or to fire it up; and often, Mr Hazlitt, we move en masse for reasons of communality. Hiking groups grow; pilgrimages endure; protest marches are a common optic and we parade endlessly; file to stadia and shops and so forth. We pave a way together.

Travelogues and memoirs, nature narratives and social histories record these journeys. But I think it is the shorter account, formally shaped or shaggy, that truly catches the trajectory of a walk. Very satisfying when the course of three or four miles unpacks over three or four thousand words. Giving the whys, hows and wherefores of a primary activity; its changes of direction and mood filling the page, its rhythms caught in the rhythms of the lines. Dickens the tireless tramper delivered a second gem: he said something always happens whilst walking, and if it happens in the head or on the road ahead then it can be laid down at essay length. Which after a few twists and turns brings me to the aim of Where My Feet Fall. I asked twenty writers to tell us about a journey made simply this. Now to keep track of them all lets be off!

***

The writers, hailing from various parts of the world and travelling various parts, were given a choice remember an old walk or report on a recent adventure. The invitation came at the beginning of the 2020 pandemic with all of its restraints, yet the second option was accepted by a goodly number. That the pandemic fails to overshadow their stories is good too. Did the relief and freedom and joy of setting out offer an alternative world for three hours, maybe three days? Footing it can do this.

So the twenty signed up and went about things, usually as one of two types. There are those who put the activity at the centre of their work call them walker-writers, in the steps of a Dickens, a Woolf, friendlier than a Hazlitt. And there are those whose feet hadnt crossed any pages until here. Also joining up are the ambulating outliers. Harland Miller says Ive always hated walking, before recalling an episode, caused by a lack of petrol, that was memorable for him alright, it was worthwhile. While Richard Ford leads the collection with mixed feelings he doesnt own the right gear, doesnt like the wrong weather, but is abroad often and happy to boot, you know it.

Ford uses a lovely bright word to depict his fellow footers, a cavalcade. For Where My Feet Fall I wanted the cavalcade to cover as many grounds as possible. Walks are had in the UK and in Europe. In North America and Australia. In India, Pakistan and Japan. During the hours of daylight, dusk and night; come rain, shine and snow. And the travels themselves? Well, some people scale the heights (not Mont Ventoux exactly, but A. L. Kennedy tackles a side of Skiddaw in Cumbria), and some get down with nature. Deeply so, into fields and forests, along lakeshores and coastlines. And city pavements invariably beckon, as do places harder to define. Suburban places for one, and the liminal, almost in-betweenish places.

Sometimes these places are so offbeat that a reason even a quest is needed to negotiate them. Or be content to drift through them without expectation. It helps Kathleen Rooneys return from the Horseshoe Casino in Hammond, Indiana, to her neighbourhood in Edgewater, Chicago. All is blaring freeways and skewed signage and sinister objects, hardly fun yet rich in the telling of. With equal curiosity and probably more love, Will Self roams an expanse of eastern Kent once more, where flaring chimneys and rusted turrets and gun-metal waters resemble a new Sublime to him. And as for suburbia itself, Pico Iyer has a home in it, at Nara not far from Tokyo. His daily amble notes how the old (the shrine) and the new (the beauty parlour) lie oddly adjacent; and how the rumblings of a dog at the gate attest to the mans foreigner status in this in-betweenish place.

From the peaks to the pavements, then. Tens of thousands of diverse steps, in diverse footwear, enjoyed in the air fine. But dont many of our walks strike a common chord in terms of physical movement, that is, and as an inner journey becomes integral to the experience. When our minds go walking too.

A figure enters the Mhlenbecker Forest, north of Berlin Rain. So much of it that I cannot see beyond the hood of my coat. It falls in sheets, vertical and sideways, on gusts of racing wind. Rain waving like laundry clipped to a line and despite the wicked weather, most senses are sharp. The visual, for sure, and the aural (crackling and slapping), and the felt (packed dampness of clay underfoot ). And though it is not exactly said, one anticipates a stream of scents wafting over this land of pine and vine. Finding such wonders as yellow pfifferlinge on the forest floor means a fair day out is had, a fair seven kilometres traversed. Only, Jessica J. Lees walk happens as much in her head as it does physically ahead. She considers the history of nearby Schloss Dammsmhle, and remembers being hereabouts in different seasons and different situations. And the lasting rain acts as an omen for what might be a final visit to Mhlenbecker.