i

Notting Hill Editions is an independent British publisher. The company was founded by Tom Kremer (19302017), champion of innovation and the man responsible for popularising the Rubiks Cube.

After a successful business career in toy invention Tom decided, at the age of eighty, to fulfil his passion for literature. In a fast-moving digital world Toms aim was to revive the art of the essay, and to create exceptionally beautiful books that would be lingered over and cherished.

Hailed as the shape of things to come, the family-run press brings to print the most surprising thinkers of past and present. In an era of information-overload, these collectible pocket-size books distil ideas that linger in the mind.

v

I am going for a walk outside the wall, having spent a long time sitting there since early morning, and on the advice of your friend and mine, I am taking my walk on the paths, for he says they are less fatiguing than here on the streets.

Phaedrus

I have the European urge to use my feet

Vladimir Nabokov

vi vii viii ix x xi xii xiii

Contents

S oon into Sauntering comes Mr Hackman, moving sketchily across a single page. Little is known of him, where he is heading for, or if he is open to foreign experiences circa the 1790s; and he makes only a sole utterance I never look up. At anything, it seems, for several years, whilst walking the length and breadth of Europe. But his words work in one way they serve as a prompt, to select accounts of the Continent being traversed by figures quite unlike this one. The pedestrian writers ahead do look up, and do look down, for on foot we connect with the world. The world comes our way. And our senses sharpen: the sights, the sounds, and the aromas; everything heightened, everything felt. So when Petrarch the poet climbs Mount Ventoux in Southern France (and pens the first pedestrian piece in 1350), it is the views that keep him going rather than any notions of glory or moral rectitude. He becomes elated by whats close at hand and whats seen from afar under our eyes flowed the Rhone. Then Lyons is outlined the bay of Marseilles the shores of Aigues-Morte Western Europe begins to unfold.

Isnt this landmass embedded in all our minds? xv To be climbed: the famous mountain ranges, like spines. To be trailed: the rivers, lakes and deltas, like arteries. Fields and forests shall be crossed. City pavements trod. And drawing closer, a multitude of buildings and boulevards, parks and people, get the steady gaze, giving rise to joy, curiosity, and bemusement as if all the responses can be trotted out with ease!

Mr Hackman fails to look up, nor does he reveal his travelling credentials. Grand Tourer or itinerant ex-soldier? Lost explorer or ex-pat author? A few of the latter wander through Sauntering; usually British or American, they want to walk their versions of Abroad into existence, regale us with responses aesthetic and soulful their lives of leisure and privilege prevail. Still, I like Edith Whartons recall of exotic Sicily (brushing against plant-life dripping and glaucus) and her idea that stepping forward triggers a mental leap backwards, near Syracuse. And its fun following the Chevalier de Latocnaye in Ireland, a French dandy sporting an umbrella stick, who tells a story at every turn of the road. One of the best describes the lost palace of Dondorlas with its fantastical flying dishes.

Wharton and the Chevalier walk well, lots of leisure seekers do not. They over-praise the picturesque and often compare European life with their lives at home. Windy, knickerbockered men of Empire typify the trend, including William xvi Makepeace Thackeray, yet he features because he makes us laugh in Brussels and Antwerp. And Joseph Roth is out and about, cautioning against the picturesque, or as he puts it, our Baedeker-ized nature. He observes crowds in a local park, hearty Berliners, before tut-tutting the need for sticks and umbrellas and loden-jackets. Why the gear!

In 1974 a young man packs his own gear into a duffel bag and tramps the minor roads from Munich to Paris. It is November, and already freezing. What he sees forms a remarkable diary. Small objects enthrall him, wet cigarette packets like corpses and cellophane wrappings dimmed from dampness; and bigger objects too as when a low-flying aircraft enables the pilots face to be visible. Evening time, he breaks into empty properties and appoints himself king of the house for a while. He is the director Werner Herzog, whose journey seems more outlandish than his famous films. For he is on a mission to walk an ailing friend back to good health, taking a tough and wayward course to her bedside in the French capital. It is an act of will. Some kind of pilgrimage.

The real pilgrim trails of Europe are ancient and multitudinous networks, running rural and urban. If not pilgrims marching, you might find others similarly disposed. Johann Wolfgang Goethe prepares for a civic procession in Palermo and has to choose between clean walking or hopping across heaps xvii of dung during a recce of the city. Also on Italian ground is D. H. Lawrence, witnessing a Sardinian custom whereby the young men of a town dress up as women, then move off as women. Unselfconsciously and as maskers! he adds, rather excitedly. Its a rackety custom, and Im not sure we get to the nub of it.

I walked through the mountains today, says Robert Walser, Swiss-born, Alps-besotted, and taking to the road to see so much. He encounters smoking trains, fellow hikers and highway children, and all becomes an enormous theatre to him. A theatre of walking types is what struck me as I sorted these extracts, with Europe acting as the mis-en-scene. Ex-pat authors, pilgrims and paraders have passed so far. Who else shall show?

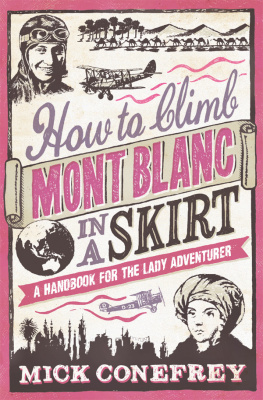

Questing types for certain. Walking to a place is often a quest, different to a pilgrimage. Up, up into the thinning air goes Henriette dAngeville, the second woman to reach the top of Mont Blanc. Shes not against the men of the team, but she wont be helped by them either, even as her strides turn to stumbles and the endeavour looks doomed. Nor would you call dAngeville a poet of the peaks, yet her words affirming success at twenty five past one on a September afternoon ring clear bravo to that. And a more recent quester is Joanna Kavenna, setting off to find the mythical land of Thule. Approaching the glacial tongue of Skaftafellsjkull (Iceland), she xviii appreciates the walkers tininess against an expanse of white. The ice doesnt cause fear, it hints at incongruity. Small details are telling, as are her words to describe the writings of an earlier visitor Richard Burtons holiday baroque.

Words come easily en route. Physical movement frees the mind, stirs up thoughts and this leads to a brilliant insight or two. Immanuel Kants walking habit is just that a habit and he probably sensed little of the external world when pacing a lime-tree avenue in Konigsberg, northern Germany. He was so precise in his practice exactly eight lengths daily that his neighbours would set their watches by him. But unknown to them what destroying, world-crushing thoughts and words were being hatched there, under the limes, according to Kants chronicler Henrich Heine.

Next page