Thank you for purchasing this Popular Woodworking eBook.

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to free content, and information on the latest new releases and must-have woodworking resources! Plus, receive a coupon code to use on your first purchase from ShopWoodworking.com for signing up.

or visit us online to sign up at

http://popularwoodworking.com/ebook-promo

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

We were so clever back in the 1960s.

In a Nixon-era book on fixing up old furniture, I once read:

Your old woodworker was a mighty clever fellow! When he built a chair, he would always choose a glue that was weaker than the wood. That way, when the chair broke, it was the glue that gave way, but the joint remained intact. All he had to do was glue it back!

So heres the picture that statement paints: Its the year 1780 and Your old woodworker stands at his bench ready to glue his chair together. He must choose carefully! He reaches for the clear bottle of Ye Glue Super but stays his hand. Nay. Twould be too strong, he mutters. His fingers move towards the jar of Old Yeller Tightly Bonding, but again he hesitates. Nay. I must build weakness into my chair! He glances at the twin tubes of A Pox of E! and shakes his head in wonderment at the bounteous choices available to him here in 1780! He knows what he must do, and as one hand dabs his brush into the old iron pot of hide glue weakened by the addition of old cheese and stale beer, his other hand strains to reach around and pat himself on his back.

To top this scene off, the photo of the broken chair seat accompanying the text showed a cheap, factory-made butt joint spanned by a pair of glue-globbed, spiral-cut dowels. The nearest your old woodworker probably got to this particular chair was cursing it as it broke under his weight at the old folks home.

This is the curse of presentism, the projection of our own cleverness onto the past, and we cannot escape it. The past is truly a foreign country that we can never visit, but as with the old maps decorated with fanciful creatures populating unknown lands, we fill in the unknowable past with needs from our own time. Yes, we always try to do better, to find a more accurate representation of the past, but our best efforts always seem to reveal less about the past than about our present selves.

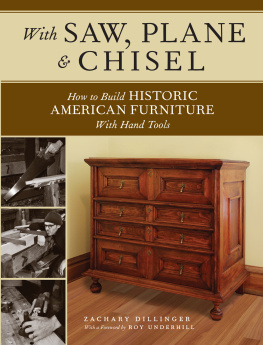

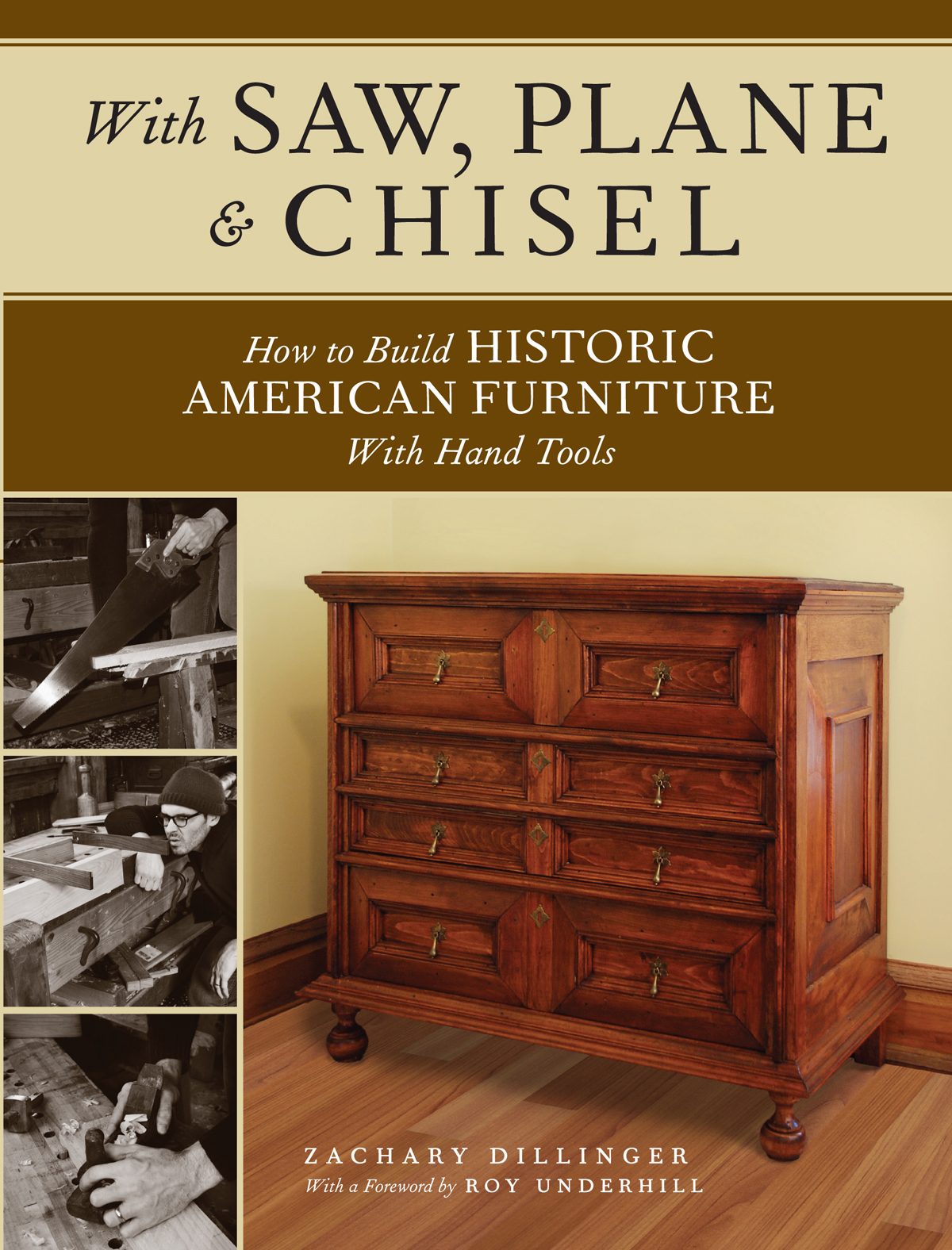

That is why With Saw, Plane & Chisel brings such good news about the times we live in today. This is not a book you would have seen in the 1960s, that distant age of motorized fishing lures, the music of J. S. Bach played on synthesizers, and high-speed, rotary, combustion-powered ways to do everything. But that was how we got to now. The technology of the jet age brought us to this point of peak stuff. Now the experience of our bodies at work has become a welcome joy. Between our hand and the wood, we now can seek that old connection, finding the most elegant and elemental instruments to carry our conversation with nature the saw, the plane and the chisel. Our dialogue of building is once again free-flowing, but not without direction. Every stroke of the plane informs the next one. Each cut adjusts to fit the one made before it. Every piece of work that you complete shows that your mind and body was there at every moment of the creation.

This book will keep you in good company as you work. There are fine pieces for you to build, spanning the great ages of American woodworking. These projects may surprise you if you are expecting baby-steps, for Zach takes you from proper hand tool technique right into building the most excellent pieces. But have courage, traveller! Because Zach confidently speaks the old language of hand tools and wood, he will show you a safe and true path to follow as you meet each worthy challenge on this fine journey.

Its been a winding road that led us here. Back in the sixties, there was a home power tool that boasted The Skill is in the Machine! So, I guess they thought we not only wanted a pitching machine for batting practice, but a hitting machine as well so we could just sit back and watch. But the desire for skill has never left us, and the effort required to achieve it still earns the greatest respect. We no more expect to just pick up a chisel and do perfect work than we expect to pick up a recorder and play Bach the first time out. The work is ours to enjoy.

Zach brings us woodworking as great music, now played again on the original instruments. This art is indeed of a specific time, but it somehow stands outside of time as well. The timeless reward resides not just in the product, but also in the process. We listen again to the sound of the saw, and once again, the sound of our work delights our hearing rather than damaging it. We can hear in our work the sharpness of the edge, the grain and seasoning of the wood. The wood and the tools speak to us as we work. Sometimes I fancy that they ask Hey! Where have you been? Theres work to be done!

Dont worry fellas! Were back!

Roy Underhill

INTRODUCTION

Why & How To Build Period Furniture

I work with period furniture because of the stories these pieces tell. From the simplest nailed blanket chest to the most elaborate Chippendale secretary, each surviving piece is a physical manifestation of a turbulent, dangerous, yet vibrant era in our history among the only tangible objects that remain, in fact. With a little knowledge and skill, you can also learn to trace the hand of the maker in these pieces. Machine tools didnt dictate the composition or execution. The furniture looks handmade because it is handmade.

In order to successfully understand, appreciate and ultimately reproduce the pieces we will study, it is imperative to understand both the construction and the domestic context of the originals. They were built by professional and semi-professional artisans for whom making furniture was a means of survival, not an enjoyable hobby. They worked long hours in less than ideal settings, often in poor light, to produce salable goods. Attention could not be lavished on every surface, and every joint was not flawless (the idea of a piston-fit drawer didnt arrive until the studio furniture movement of the mid-20th century). In short, these men and women were making a living producing the best work they could within considerable limitations.

Being consumer goods, these pieces had to meet the demands of the customer. That reality connects them closely to their time period, if you know what to look for. The fact that period houses lacked electric lighting and climate control explains many of the construction techniques and imperfections. The carved, inlaid and veneered ornamentation speak of a society that valued conspicuous consumption. Perhaps even more interesting are the pieces that can only aspire to that status, simulating expensive decorative techniques with the skillful use of paint and relying on a fair bit of eye-squint in the candlelit rooms of the time. These pieces speak of a middle class that envied the latest fashions of the well-heeled, letting us look back 200 years to glimpse a society that shared many of our own motivations.