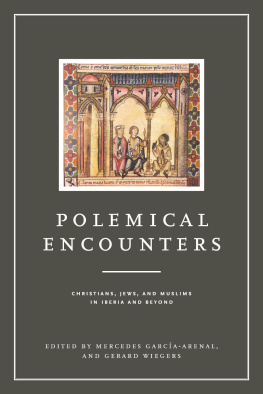

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

We would like to express our gratitude to our benefactors from the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev for their valuable assistance in financing the publication of this volume: the Universitys Rector, the Dean of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences and the Center for the Study of Conversion and Inter-Religious Encounters (CSoC). Our thanks go to Katharine Handel for her meticulous and overall excellent editing work and to Yoav Meyrav for generously taking upon himself the task of reviewing the Hebrew and Arabic transliterations. We thank Asher Binyamin and The Goldstein-Goren International Center for Jewish Thought for providing helpful administrative assistance. Finally, we are truly and deeply grateful to each and every contributor for willingly accepting our invitation to participate in this volume.

I On Daniel J. Lasker and his Scholarship

Prof. Daniel J. Lasker Scholar, Teacher, and Friend

Howard Kreisel

The number of Prof. Laskers publications is staggering 8 books, 4 edited volumes, over 120 scholarly articles, 84 book reviews, 27 encyclopedia articles, and scores of other assorted publications. The breath of his interests is equally impressive, including not only the whole gamut of medieval Jewish (and Karaite) thought, but also diverse issues in the field of Jewish medical ethics as well as the Jewish calendar. The caliber of the institutions in which he has taught over the years attests to his stature in the field among them, Yale, Princeton, University of Toronto, Ohio State, University of Washington, University of Texas, Yeshiva University, Queens College, and Boston College. From 1978 his home has been Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, where he has been and remains one of the mainstays of the Goldstein-Goren Department of Jewish Thought. Up to his retirement in 2017 he held the Norbert Blechner Chair in Jewish Values, and for many years ran the center affiliated with this chair. He served two terms as the head of the Jewish Thought track, when this track was still part of the Department of History, and from 20052008 he served as chair of the Goldstein-Goren Department of Jewish Thought. In addition, from 2009 till the present he serves as vice president of the Society for Judaeo-Arabic Studies. 9 Ph.D. students have completed their dissertations under his supervision (our department was given the right to train Ph.D.s only close to the turn of the century). Some of them have contributed to this volume, and who in their appreciation of their academic mentor took the initiative to organize it and prepare it for publication.

I would like to take this opportunity to speak about the person behind these dry, albeit extraordinary, statistics. According to Danny (as I will refer to him in the rest of this introduction), we met for the first time in the summer of 1964 as campers in the opening year of Camp Ramah in the Berkshires. Since we were in different bunks, and even divisions, I confess I have no recollection of this meeting. I do remember much of the summer quite distinctly, as well as some of the staff we had: Chaim Potok was head of the older division, Reuven Kimelman was a camp counselor in Dannys division, David Weiss Halivni was scholar in residence. Danny informs me that his counselor during the first week in camp was Art Green (though he too I dont remember from this period). I wouldnt even begin to mention the illustrious careers some of our fellow campers subsequently embarked upon. My first distinct memory of meeting Danny, however, has to wait for another four years when I began my freshman year at Brandeis in the Fall of 1968. Danny was already a sophomore that year. While we each had a different set of friends, we saw each other quite regularly at Hillel events (particularly Sabbath services and meals). Interestingly, though we both shared common academic interests (philosophy and Judaic studies), we had no courses in common. Still, already at an early date Danny, together with one of his closest friends at Brandeis, Larry Schiffman, were becoming something of a legend among the Judaic studies crowd tremendously gifted students, industrious, very focused and in a great hurry to complete their degrees and get on with life. For me, given the atmosphere at Brandeis at the time, like that of many other liberal college campuses, this was an incredible phenomenon. Ours was the era of the hippie generation (Woodstock was to take place in the summer of 1969), of radical politics (building takeovers in my freshman year by black students and their numerous radical white student supporters at colleges all over America, including Brandeis, followed in my sophomore year by nationwide campus strikes protesting the Vietnam War). Jewish causes too were not lacking (support of Israel and of Russian Jewry). It was simply a period when it was hard to single mindedly devote oneself to ones studies, with a clear view of where one was going in life. So many of us were busy searching for our identity in this formative period of our lives, or caught up in some of the pressing causes of the time. Even something as simple as choosing a college major took me my entire freshman year. To meet someone like Danny with such a pure sense of academic direction in this period, and so driven to achieve his aims quickly, was certainly unusual.

Danny actually thought of becoming a rabbi before he realized that his true calling was that of a scholar. The figure who was to exercise a decisive influence on the course of his life was Prof. Alexander Altmann, with whom Danny began studying already in his freshman year at Brandeis. Prof. Altmann was indeed the model of the consummate scholar a complete master in medieval Jewish philosophy and in Kabbalah, an expert in rabbinic thought, Hasidic thought and medieval Arabic philosophy, as well as the worlds leading authority on Moses Mendelssohn. Moreover, the whole personality, appearance and very speech of this Hungarian born and Berlin trained Jew was that of a scholar of the old world from bygone times. To this day, it is hard to think of him without a feeling of awe (and yes, our own inadequacy by comparison). He trained his students more by example than anything else. He conveyed to them what he expected them to learn, and then left them to flourish (or not) on their own. What he expected was that you engage in scholarship. This entailed command of the primary sources in their original language (and hence the need to learn the languages of the primary sources), knowledge of all the relevant secondary literature, and presentation of your accumulated expertise and insights in a concise, well organized, and lucid manner. Prof. Altmann (and to Danny and me, as well as to everybody who ever met him, he will always be