2016 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016937702

ISBN 978-0-252-04029-0 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-252-08174-3 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-252-09855-0 (e-book)

Joy Harjo Poem (): Perhaps the World Ends Here, from The Woman Who Fell from the Sky by Joy Harjo, Copyright 1994 by Joy Harjo. Used by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to John Finn, Lee Friedman, Wendy Sarvasy, and Jacob Flammang Friedman for reading drafts of this book and providing excellent comments. The following people were very helpful with sources, contacts, and ideas: Shirl Buss, Alexander Flammang Friedman, Karen Gross, Gail Killefer, James Lai, Kira Marchenese, Peter Minowitz, Ann Rankin, Eric Shutt, and Kathleen Wareham. I am grateful for the interviews with Stephanie Bonham, Michael Curtis, Nancy Highiet, Emma Le Duc, Renee O'Harran, Seamus O'Leary, Barbara Scheifler, and Malcolm Sher. Finally, my thanks to family, friends, colleagues at Santa Clara University, and editors at the University of Illinois Press for their support and encouragement.

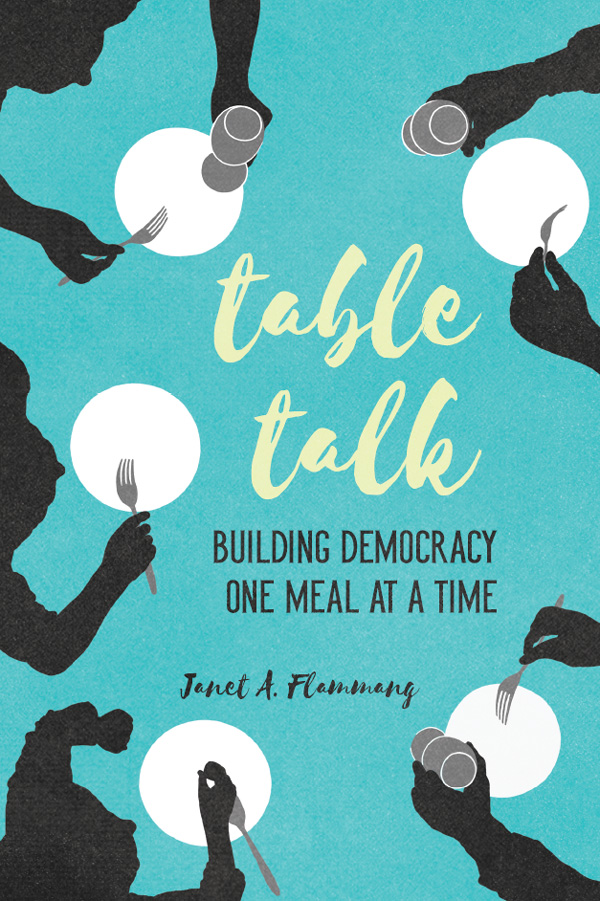

Introduction

How do we develop a political voice? How do we learn to express our feelings and ideas about authority, a common good, democracy, duty, equality, fairness, freedom, justice, legitimacy, liberty, loyalty, obligation, oppression, order, patriotism, power, repression, respect, responsibilities, and rights? I list these political concepts in alphabetical order in recognition that we all differ in our ranking of their relative importance. Nevertheless, they are bedrock features of politics. I invite you to join me on a political archeological expedition to explore the deep layers of meaning we give to our political understandings. You will notice that my emphasis is not on electoral politicsvoting, aligning with a political party, or joining an interest groupabout which much has already been written. Instead, my interest is in taking a look at our political worlds from a different angle by investigating the deeper layers of social and cultural relations that undergird electoral politics.

This is the territory of civil society, where we learn that people act, not only selfishly, but also for a common good; where people attend to our basic needs, even though there is not an obvious reason why they should do so; where we are listened to, even when we express thoughts that challenge conventional wisdom; where our experiences are understood, even if they are not approved of; where we learn new concepts that capture what we mean; where we express our feelings and ideas for the first time in our own words. Unless we have these experiences, there is little reason to bother imagining, let alone promoting, any kind of common good.

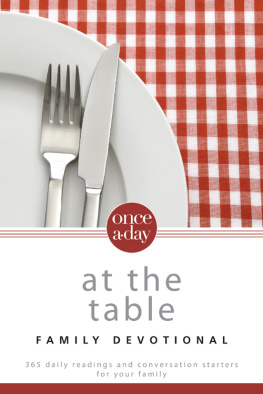

I propose two helpful guides for our exploration: the art of conversation and table activities. We can develop our civil selves by sharing food and ideas at tables where there are ground rules about listening, sharing, and respect. Of course, not all conversations and table activities have such ground rules. Meals might be marked by tension, rivalries, and tears; conversations might start out well but degenerate into shouting matches and insults. The point I want to make in this book is probabilistic: that conversations and table activities are likely occasions for developing our civil selves, and that not taking advantage of their civilizing potential is a lost opportunity. Eating is something we do frequently, and most of us prefer table experiences that are civil. Of course, there are cultural differences in rules about civil tableswho should speak, when and how; what behavior is acceptable; what topics are off limits; and how conflict should be resolved. Indeed, it is our daily exposure to the making, enforcing, and breaking of these rules that constitutes our daily doses of political awareness, growth, and transformation. It is at tables and in conversations that we make sense of the many layers of our experiences with political import.

The best way to excavate these layers of meaning is by telling and listening to people's firsthand accounts of their lives expressed in stories. Stories are rich with emotions and ideas, personal and group history, hopes and dreams. We tell stories in order to make sense of the many facets of our experiences, to put disconnected parts into some kind of whole, and we tell lots of stories in table conversations. When we listen to people's political narratives, we hear contradictions, ambivalences, and nuances, and we want to learn how they make sense of their political world.

The goal here is understanding, not explanation. Understanding gives equal weight to two meanings: that presented by the storyteller and that given by the listener. As the listener, I will present social science studies and concepts that I think help us understand the stories included in this book. But at the same time, I will present people's understandings in their own words in order to honor the variety of human experience in developing a political voice while sharing ideas in conversations and at tables.

In listening to these stories, I am particularly interested in what makes us resilient. In politics many disappointing, even horrific, things happen, and one can reasonably ask why in light of these events people keep imagining and trying to bring about improved political arrangements. My supposition is that there is a cumulative positive effect of being respected, listened to, taken seriously, and trusted, and that these experiences create a reservoir of value and strength for the common good, for a collectivity beyond those in our immediate contact, that can be drawn upon in political setbacks. Stories remind us that others have survived seemingly unbearable forms of being beaten down; that there are novel and creative ways out of apparently hopeless situations; and that humans can relate in ways that generate more light than heat.

This migrant family shares a noonday meal on an Oklahoma roadside in 1939. During the devastating dust bowl, when many people could not afford a table, table rituals helped maintain group cohesion and build resilience.

Credit: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection (LC-USF 33-012275-MS).

We become resilient when we feel connected. Stories, conversations, and table activities are important and everyday ways of connecting with others. They might be occasions where we empathize with someone we have not been comfortable with before. A vibrant civil society depends on feelings of respect, trust, and empathy, which in turn make possible the idea of a common good that is worth working toward. It also depends on having people with conversational skills. Conversations take work, and not all people are up to the task or think that it is their responsibility to learn or teach the art of conversation. My hope is that after reading this book, readers will be convinced that mealtime conversations are the building blocks of democracy and that conversational skills can, and should, be learned one meal at a time.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.