ALSO BY ROBERT PAARLBERG

The United States of Excess

Food Politics

Starved for Science

The Politics of Precaution

Policy Reform in American Agriculture

(coauthored with David Orden and Terry Roe)

Leadership Abroad Begins at Home

Countrysides at Risk

Fixing Farm Trade

Food Trade and Foreign Policy

this is a borzoi book

published by alfred a. knopf

Copyright 2021 by Robert Paarlberg

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

constitutes an extension of this copyright page.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Paarlberg, Robert L., author.

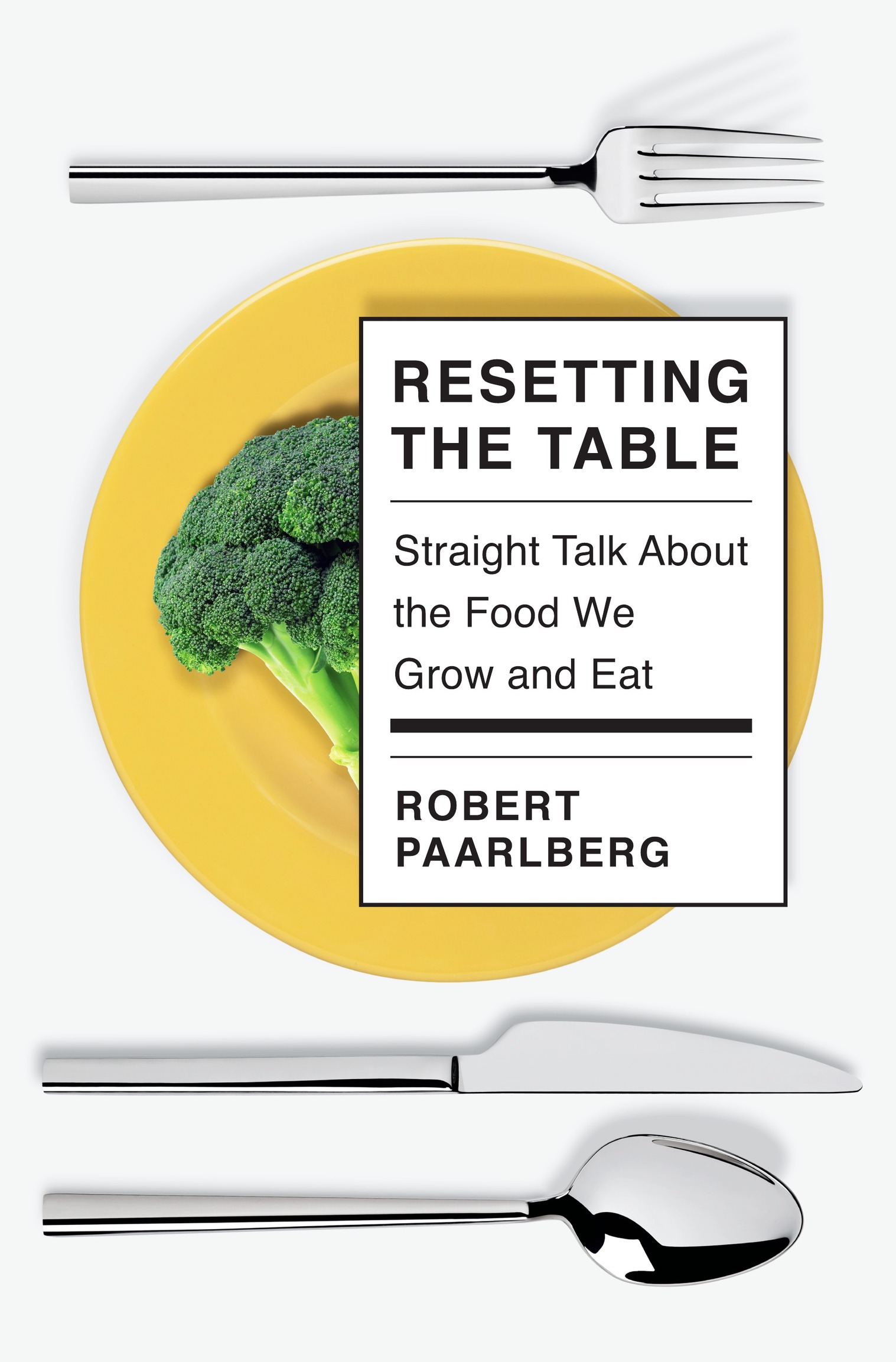

Title: Resetting the table : straight talk about the food we grow and eat / Robert Paarlberg.

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2020. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019050600 | ISBN 9780525656449 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780525656456 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Food industry and tradeUnited States. | FarmsUnited States. | AgricultureEconomic aspectsUnited States.

Classification: LCC HD9005 .P25 2020 | DDC 338.1/973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019050600

Ebook ISBN9780525656456

Cover images: (table setting) ersinkisacik / E+ / Getty Images; (broccoli) Francesco Perre / EyeEm / Getty Images

Cover design by Kelly Blair

ep_prh_5.6.1_c0_r0

To Marianne,

for absolutely everything

Surely, I said, knowledge is

the food of the soul.

Socrates

Introduction

In 2008, I was attending a panel discussion on sustainable food at Harvard University, in the storied Faculty Room of University Hall. The purpose of the panel was to promote and celebrate good food, so we were served tasty hors doeuvres carefully sourced from local farmers and fishermen, beginning with demitasse cups of a delicious scallop chowder from Cape Cod Bay. The featured speakers were a celebrity restaurateur from the San Francisco Bay Area, a playwright from New York, and the young leader of Slow Food USA. It didnt take long for all three to reach a lockstep conclusion: In the future, they said, sustainable food would have to be organic, local, and slow, definitely not fast or industrial.

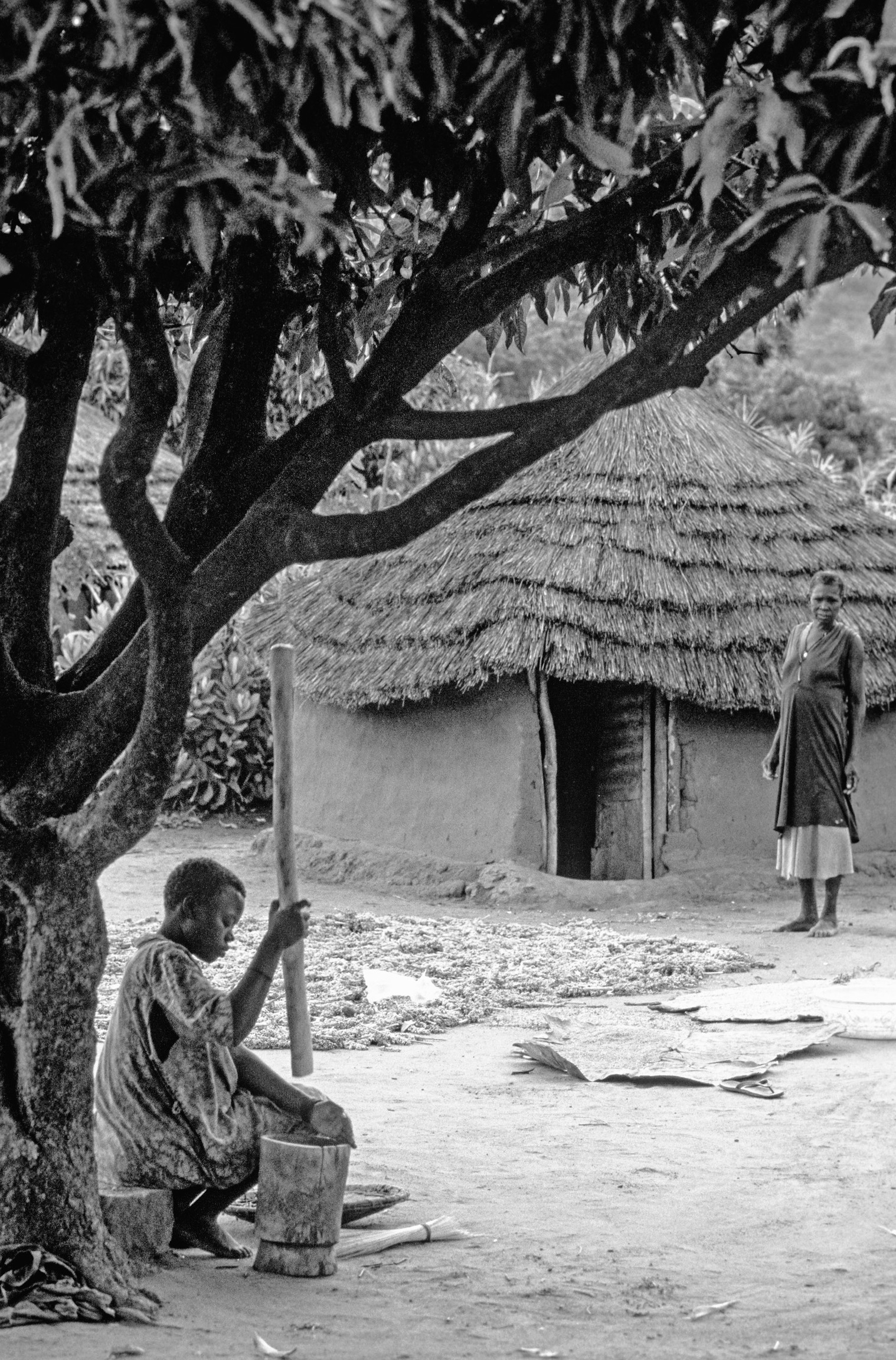

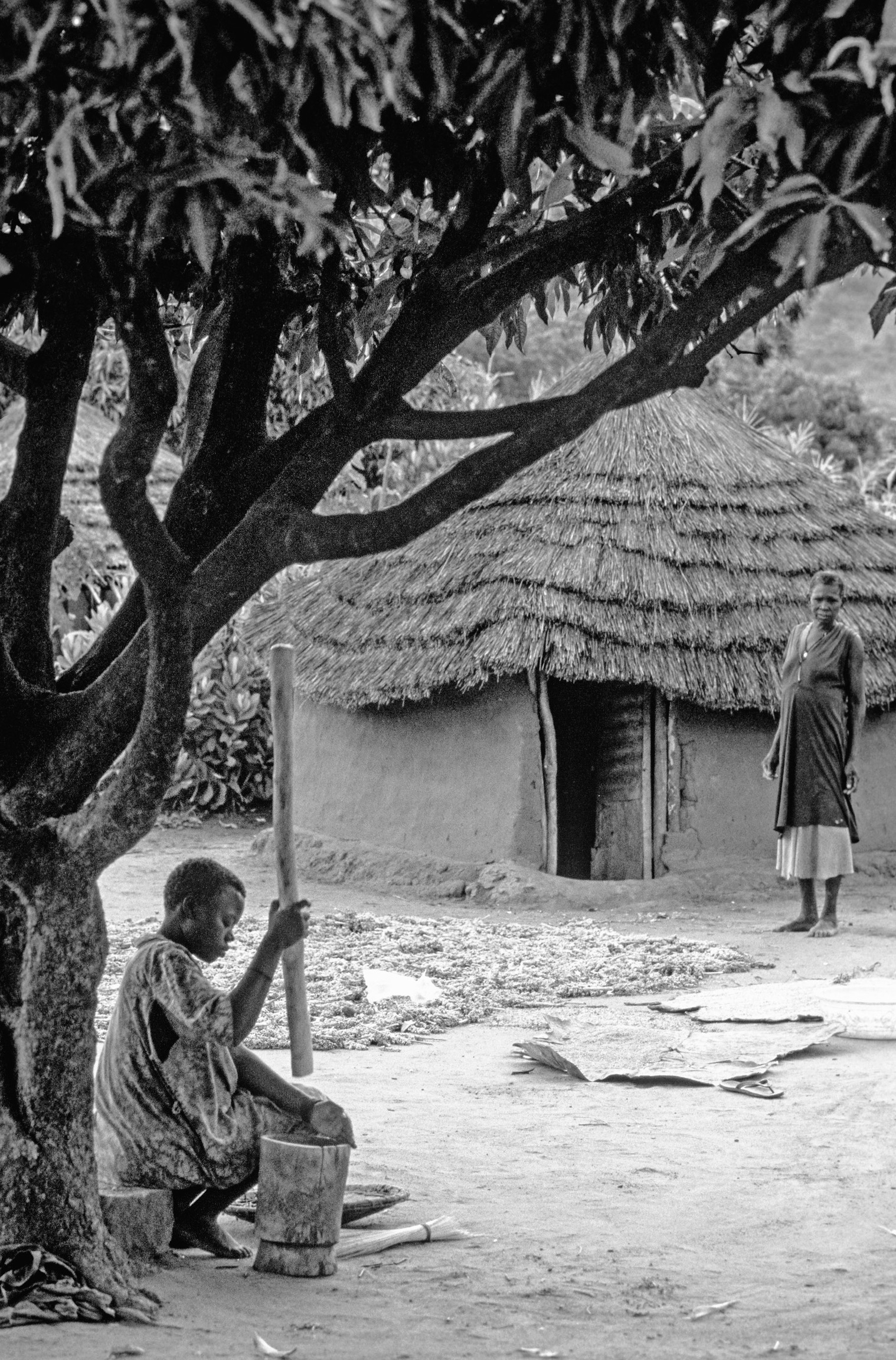

Those at the event nodded their heads in assent, but I had a different take, having just returned from a research trip to rural Africa. I had been interviewing farmers in Uganda who were trapped inside a food system that was entirely organic, local, and slow. The women I had spoken with (most African farmers are women) did not know it, but they were living an extreme version of the Harvard dream. They were organic because they could not afford any nitrogen fertilizer; their food was all local because the rutted dirt roads made transport almost impossible during the rainy season; and their daily food preparation tasks were laboriously slow. Before cooking a porridge meal for their family these women had to strip, soak, dry, and then pound the maize kernels into flour, then carry in wood to build a fire plus water for the pot. Despite these efforts, many of their children were stunted from poor nutrition.

Pounding maize in Uganda, where slow food preparation is an everyday experience, and a daily burden for women and girls.

Farmers are important to me for personal as well as professional reasons. Both of my parents were from a farming background, and as a young teenager in the summer months I worked on my uncles Indiana farm, alongside my older brother and two cousins. We got up early to feed the cattle and hogs in the dark, before sitting down to our own breakfast. My cousins were still too young to drive a car, but they were handling powered machinery, working with animals four times their size, and they already knew things about farming well beyond the ken of most playwrights or big-city restaurateurs.

Discussions of food today can quickly turn into discussions about farming. Consumers not only want food to be tasty, safe, nutritious, and affordable; they also want it to come from farms that protect the natural environment, respect the welfare of animals, help sustain rural communities, and give hired workers a living wage. I share all of these goals, but my prescriptions differ from the Harvard panels dream. My research experience tells me not to yearn for an organic, local, or slow food system, since that would mean abandoning a centurys worth of modern science. It would force farmers to accept more toil and less income, consumers would be given fewer nutritious food choices, and greater destruction would be done to the natural environment. All this will be explained.

The use of modern science is broadly welcomed in medicine, transport, and communications, yet it has become strangely controversial in food production. Many of my friends in Massachusetts, where I live and work, hold a view that modern farming has become far too industrial. They agree with Mark Bittman, a former New York Times columnist, who blames industrial farming for having spawned an obesity crisis, poisoned countless volumes of land and water, wasted energy, tortured billions of animals. They would also agree with Philip Lymbery, the author of Farmageddon, who concludes that every day there is a new confirmation of how destructive, inefficient, wasteful, cruel and unhealthy the industrial agriculture machine is. We need a total rethink of our food and farming systems before its too late.

As their preferred alternative, many of my friends imagine a return to small, local, and chemical-free (organic) farms. These farms should produce a traditional mix of both crops and animals, as opposed to the specialized, industrial-scale farms that today produce just one or two crops and probably have no animals at all. When it comes to buying food, my friends would rather not be seen shopping in supermarkets, since too many items on the shelf are heavily processed or have traveled too many food miles. Their ideal, when they have plenty of time, is to buy unprocessed foods directly from local growers at a farmers market, or from a community supported agriculture (CSA) farm. They admire Alice Waters, proprietor of the acclaimed Chez Panisse restaurant in Berkeley (she was one of the speakers on the 2008 Harvard panel), who states with pride that she has not set foot in a supermarket for the past twenty-five years.