The Textual Life of Savants

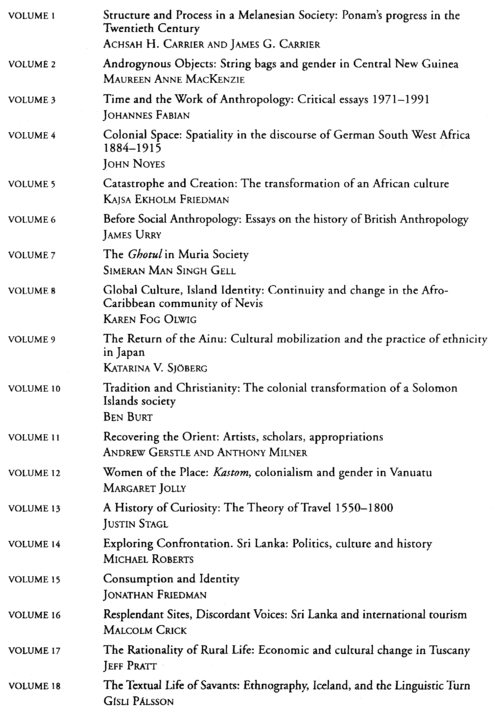

Studies in Anthropology and History

Studies in AnthropoLogy and History is a series that will develop new theoretical perspectives, and combine comparative and ethnographic studies with historical research.

Edited by Nicholas Thomas, The Australian National University, Canberra.

This book is part of a series. The publisher will accept continuation orders which may be cancelled at any time and which provide for automatic billing and shipping of each title in the series upon publication. Please write for details.

First published 1995 by Harwood Academic Publishers.

Reprinted 2004 by Routledge,

Published 2013 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

COPYRIGHT 1995 BY Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Gsli Plsson

The Textual Life of Savants: Ethnography, Iceland and the Linguistic Turn.

( Studies in Anthropology & History,

ISSN 1055-2464; Vol. 18)

I. Title II. Series

949.12

ISBN 3-7186-5721-X (hardcover)

ISBN 3-7186-5722-8 (softcover)

| DESIGNED BY | Maureen Anne MacKenzie

Em Squared, Main Street, Michelgo, NSW 2620, Australia |

| FRONT COVER | "Mountain" (artwork by Sigurur Gumundsson, 1980-1982), reproduced by kind permission of the artist. |

This book focuses on the role and significance of texts and textualism for anthropology and ethnography and, more specifically, the understanding of particular aspects of Icelandic society and history. The discussion is centred on a range of issues; moving between general social theory and ethnographic details, the immediate present and the distant past, language and production, fieldwork and the act of writing, texts (sagas, novels, and ethnographies) and "real" life. In each case, however, it draws attention to what may be called a "pragmatist" approach, a concern with action and agency as they constitute, and are constituted by, social life. Such an approach, I hold, is an important and timely remedy to current textualism, the trendy theoretical tradition often described as the linguistic turn.

Different parts of the book have been written with different contexts and purposes in mind over a period of five years or so, during which I have modified my views on several pertinent issues. Although most of the earliest material has been extensively revised to suit the present context, the reader may detect some inconsistency in both concepts and argument. I fully agree that conceptual coherence is an academic virtue, but our language necessarily retains some traces and relics from the past, our past and that of others. Some literary scholars refer to the polyphony of language and plurality of voices with die notion of "intertextuality" (see Tannen 1989: 12), faithful as they are to the facts of texts. I find it more relevant and revealing, as readers of this book are bound to notice, to use the Malinowskian metaphor of the "long conversation". Each of us is necessarily engaged in a continuous dialogue with colleagues, critics, and "informants" and, of course, ourselves.

Dialogue does allow for reading, writing, and the interrogation of texts. My interest in early Icelandic history and the saga literature began during my early days as a postgraduate student in Manchester, England, when I came across an article by Victor Turner on Njls saga, one of the so-called family sagas. Earlier, as a student in my native Iceland, I tended to think of the sagas, an obligatory reading at almost every stage of learning, as rather boring stuff, at any rate not for anthropologists. Turner managed to change my mind. The sagas, I thought, would be an exciting site for "fieldwork". It took me some fifteen years, however, to actually do something along those Lines. While the reading of texts is an important form of dialogue, especially in the case of academics, dialogue, above all, is a mutual collaboration of socially constituted subjects rooted in history and social life, not just an exchange between autonomous, alienated beings. This book, in fact, is the product of discussions I have had with a number of people representing several rather different discursive communities. Not only has the work presented here been informed by discussions with fellow academics, but there have been general theoretical developments in the di scipline, in the form of influential anthropological texts, and also persistent dialogues with Icelanders from different walks of life who have continued to provide useful and interesting topics and perspectives fishermen, fish-workers, anthropologists, linguists, saga-scholars, and, last but not least, university students. Teaching at a small anthropology department at a small university, I have been forced (or, better, "allowed") to work on a range of themes and subjects and over the years I have taught a variety of courses, including "Ethnolinguistics", "Fishing Adaptations", "The Anthropology of the Sagas", "Ecology", and "Social Theory". For me, dialogues in the classroom have frequently been a source of inspiration and learning.

For an anthropologist, the experience of fieldwork, usuallly outside the academy, is a crucial phase of learning. The chapter on language is partly the result of discussions with fellow Icelanders, focusing on language policy and the politics of language. Similarly, the chapter on fishing, partly a revision of ideas expressed in some of my earlier writings, is very much a product of an extended discussion with Icelandic fishermen. My original fieldwork, on the south-west coast in 1979 and 1981, was part of the work for my doctoral dissertation at Manchester University. Later, in 1993 and 1994, I revisited the communities I had stayed in with new questions in mind. I have learned, as many people have before me, that fieldwork is not only important for the collection of "data" but also for the development of ideas. Fortunately, learning sometimes involves having a good time. I am reminded of an amusing moment of personal discovery during my earlier fieldwork. Once a fish producer in the community where I worked, who was expecting to export dried fish (stockfish) destined for Nigeria, showed me an article in the latest issue of The Economist about the instability of the Nigerian coalition government caused by tribal conflicts and interests. Worried by rumours about the negative prospects for stockfish marketing, he asked me to summarize the contents of the article in Icelandic - adding, in characteristic humour with a decidedly sophisticated expression on his face, "we only read French here!". This event brought home to me the immediate relevance of news from the larger world, of economic relations between "my place" and some of the tribal societies that had been documented in detail by anthropologists.