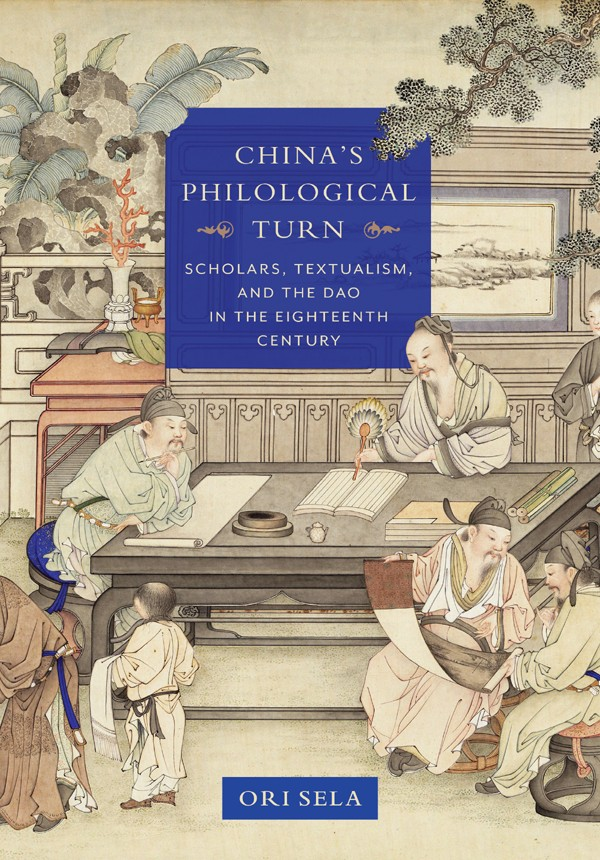

Ori Sela - Chinas Philological Turn: Scholars, Textualism, and the Dao in the Eighteenth Century

Here you can read online Ori Sela - Chinas Philological Turn: Scholars, Textualism, and the Dao in the Eighteenth Century full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018, publisher: Columbia University Press, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Chinas Philological Turn: Scholars, Textualism, and the Dao in the Eighteenth Century: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Chinas Philological Turn: Scholars, Textualism, and the Dao in the Eighteenth Century" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

In eighteenth-century China, a remarkable intellectual transformation took place, centered on the ascendance of philology. Its practitioners were preoccupied with the reliability of sources as evidence for restoring ancient texts and meanings and with the centrality of facts and truth to their scholarship and identity. With the power to construct the textual past, philology has the potential to shape both individual and collective identities, and its rise to prominence consequently deeply affected contemporaneous political, social, and cultural agendas.

Ori Sela foregrounds the polymath Qian Daxin (17281804), one of the most distinguished scholars of the Qing dynasty, to tell this story. Chinas Philological Turn traces scholars social networks and the production of knowledge, considering the texts they studied along with their reading practices and the assumptions about knowledge, facts, and truth that came with them. The book considers fundamental issues of eighteenth-century intellectual life: the tension between antiquitys elevated status and the question of what antiquity actually was; the status of scientific knowledge, especially astronomy, mathematics, and calendrical studies; and the relationship between learned debates and cultural anxieties, especially scholars self-characterization and collective identity. Sela brings to light manuscripts, biographies, letters, handwritten notes, epitaphs, and more to highlight the creativity and openness of his subjects. A pioneering book in the cultural history of intellectuals across disciplinary boundaries, Chinas Philological Turn reconstructs the history of eighteenth-century Chinese learning and its long-lasting consequences.

Ori Sela: author's other books

Who wrote Chinas Philological Turn: Scholars, Textualism, and the Dao in the Eighteenth Century? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.