2015 by the University of Washington Press

Printed and bound in the United States of America

Composed in Minion Pro, typeface designed by Robert Slimbach

18 17 16 15 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

University of Washington Press

www.washington.edu/uwpress

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hu, Minghui.

Chinas transition to modernity : the new classical vision of Dai Zhen / Minghui Hu.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-295-99476-5 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Dai, Zhen, 17241777. 2. Philosophy, Chinese16441912. 3. ChinaIntellectual life16441912. 4. ChinaHistoryQianlong,

17361795. I. Title.

B5234.T324H83 2015

181'.11dc23

2014050175

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My interests in both Chinese history and the history of science commenced at UCLA. Benjamin Elman and Theodore Porter consistently and methodically guided me through difficult and uncertain times; Joyce Appleby, Perry Anderson, Ted Huters, and Sharon Traweek all left important imprints in my intellectual formation. Kenneth Pomeranz kindly offered me my first academic position at the University of California, Irvine, in 2002. Prasenjit Duara selected me to be his postdoctoral fellow at the University of Chicago from 2003 to 2005. Their support in launching my career is truly appreciated. Many institutions nudged me along my journey as a professional historian: the Needham Research Institute, the Institute of Modern History at Academia Sinica, the Ricci Institute at the University of San Francisco, Tsinghua University, Korea University, the Vatican Library, the British Library, the Library of Congress, Bibliothque nationale de France, the Fu Sinian Library at Academia Sinica, the Institute of Qing History at Renmin University, the Palace Museum in Beijing, and the Palace Museum in Taipei. The following foundations provided me with financial support that eventually led to the completion of this book: the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Ricci Institute at the University of San Francisco, the Center for the Pacific Rim Studies at the University of California, the academic senate committee on research and the Institute of Humanities Research at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and Academia Sinica.

I started this book soon after I joined the faculty in the Department of History at the University of California, Santa Cruz. My East Asian colleagues at Santa Cruz, including Gail Hershatter, Emily Honig, Noriko Aso, Alan Christy, Christopher Connery, and Lisa Rofel gave me a nourishing and stimulating intellectual home. Many friends and colleagues read and commented on the entire manuscript or parts of it: R. Kent Guy, Laura Hostetler, J. G. A. Pocock, Sam Gilbert, Isabelle Landry-Deron, Chu Pingyi, Lu Miaw-fen, Chang So-an, Jiangping Chen, Catherine Jami, Guy Allito, Edward Shaughnessy, Toby Huff, Franoise Waquet, Wang Hui, Charles Hedrick, and Nathaniel Deutsch. I owe special gratitude to Gail, Kent, and So-an, who are the unwavering supporters of this book. My special thanks to Dong Jiangzhong, who translated and helped publish earlier forms of chapters five and seven in Chinese. My editor, Lorri Hagman, continued to support me with integrity and honesty. She is the best editor one could hope for. The production team at the University of Washington Press is also outstanding, and I would like to thank Jacqueline Volin for her attention to detail.

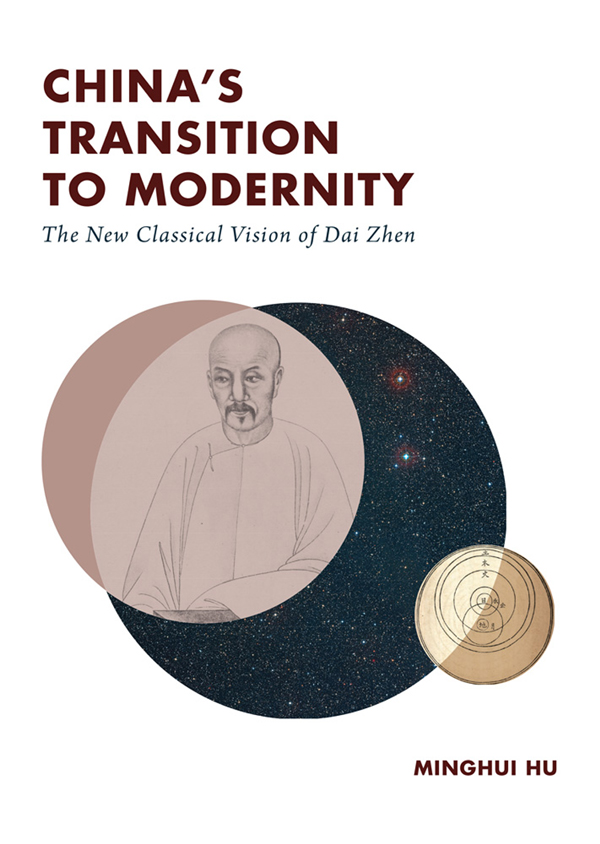

A note about the cover image: Dai Zhens portrait is included in the collection The Portraits of Qing Scholars (Qingdai xuezhe xiangzhuan), volume 1. The first of the two volumes originated from the private collection of the painter and scholar Ye Yanlan (1823-98), one of many students who attended the Hall of Sea Learning (Xuehai Tang), the private Confucian academy founded by Ruan Yuan in Canton in 1820. Ye Yanlan studied under the leading instructor Chen Li (1810-82), who advanced the intellectual agenda of evidential scholarship movement. Ye passed the metropolitan exam in 1856 and managed to navigate through the Taiping civil war to the end of the Sino-Japanese War in 1895. He claimed that he had collected many authentic portraits of Qing scholars from reliable sources. He Yikais recent monograph A Study of the Portraits of Qing Scholars identifies and confirms these sources.

After inheriting the family collection, Ye Gongzuo (1881-1968, Ye Yanlans grandson), edited and published most of his grandfathers lifelong work in 1928, to immediate acclaim from intellectual celebrities. Ye Gongzuo experienced the fall of the Qing dynasty and the political ups and downs of the new republic; he was appointed to several minor positions on cultural affairs during the republican years. Throughout his career, he continued to collect and copy portraits of other Qing scholars and published the second volume in 1953, which he submitted to Mao Zedong. Mao expressed interest in the collection, asking him: May I read the first volume as well?

Perhaps as a result of Ye Yanlans evidential training with the accuracy and reliability of the authentic portraits as well as his fascination with photography later in his life, The Portraits of Qing Scholars is endowed with an eerie sense of photorealism. Dai Zhens portrait also conforms to his friend Hong Bangs description of Dais physical appearance.

What else can I say to Chiung-chi and our daughter, Clio? Raising Clio with Chiung-chi has been just as exhilarating and frustrating as writing this book. I have enjoyed every minute of our life together, even during intractable challenges.

CHINAS TRANSITION TO MODERNITY

CHAPTER 1

THE MAN AND HIS TIMES

Individuality was subversive in imperial China. Dai Zhens 1776 book An Evidential Analysis of the Meaning of Terms in the Mencius (Mengzi ziyi shuzheng) would come to be recognized as a fully developed and systematically articulated vision of the new individuality in China, but when it was first published, it failed to arouse much interestjust the occasional condescending remark about a lowly scholar without an examination certificate speaking about challenging philosophical principles. It was not until the twentieth century that historians began to identify the text as the fusion of early modern individualism and objective methodology, a blow against the Neo-Confucianism that had dominated the intellectual and cultural scene in China for centuries.

In early modern China, individualism was not typically articulated in philosophical or political discourses. It was buried in commentaries on the classical scriptures. By conceiving of the individual as a social unit rather than a thinking or moral subject, Dai Zhen (172477) began to systematically articulate the social, economic, and biological needs of each individual in society. This intellectual agenda was cleverly disguised in his studies of ancient texts and appeared to conform to the acceptable practices in a rather long commentary tradition of the Confucian canon.