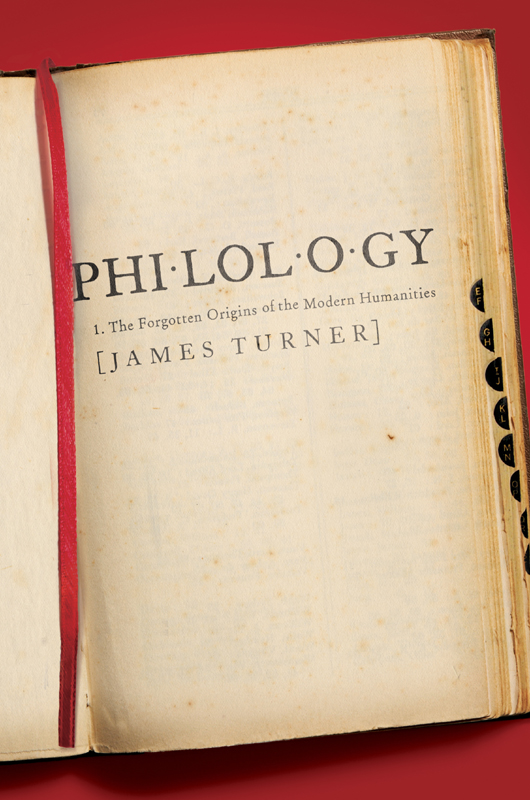

PHILOLOGY

PHILOLOGY

THE FORGOTTEN ORIGINS OF THE MODERN HUMANITIES

James Turner

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2014 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Cover design by Faceout Studio, Kara Davison

Cover image iStock Photo

Endpaper map: Mare Internum, from Richard J.A. Talbert, ed., The Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. 2000 Princeton University Press.

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Turner, James, 1946 author.

Philology : the forgotten origins of the modern humanities / James Turner.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9780-691145648 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. PhilologyHistory. 2. Historical linguistics. 3. Humanities. I. Title.

P61.T87 2014

409dc23

2013035544

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Minion Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

FOR MY DOKTORKINDER WITH THANKS FOR ALL THEY TAUGHT ME

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

I n his Adages (1500) the great humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam quipped, The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog one big thing. I have more to say about how I got curious, but first a few words are in order about what our fox and hedgehog comprehend.

Studia humanitatishumanistic studiesin one guise or another have for many centuries dwelled at the heart of Western learning. In British, Irish, and North American universities today, the humanities make up a central strand of teaching and research. But their present forms are a modern novelty. The many humanistic disciplines that todays fox knows date only from the nineteenth century. Trace their several origins, and (as the hedgehog realizes) the trail usually leads back to one big, old thing: philologythe multifaceted study of texts, languages, and the phenomenon of language itself.

Philology has fallen on hard times in the English-speaking world (much less so in continental Europe). Many college-educated Americans no longer recognize the word. Those who do often think it means no more than scrutiny of ancient Greek or Roman texts by a nit-picking classicist, while British readers may take it as referring only to technical research into languages and language families. Professors of literature use the term to belittle a simpleminded approach to their subject, mercifully discarded long ago. Indeed, for most of the twentieth century, philology was put down, kicked around, abused, and snickered at, as the archetype of crabbed, dry-as-dust, barren, and by and large pointless academic knowledge. Did I mention mind-numbingly boring? Whenever philology shows its face these days in North America or the British Islesnot often, outside of classics departments or linguistics facultiesit comes coated with the dust of the library and totters along with arthritic creakiness. One would not be startled to see its gaunt torso clad in a frock coat.

It used to be chic, dashing, and much ampler in girth. Philology reigned as king of the sciences, the pride of the first great modern universitiesthose that grew up in Germany in the eighteenth and earlier nineteenth centuries. Philology inspired the most advanced humanistic studies in the United States and the United Kingdom in the decades before 1850 and sent its generative currents through the intellectual life of Europe and America. It meant far more than the study of old texts. Philology referred to all studies of language, of specific languages, and (to be sure) of texts. Its explorations ranged from the religion of ancient Israel through the lays of medieval troubadours to the tongues of American Indiansand to rampant theorizing about the origin of language itself.

The word philology in the nineteenth century covered three distinct modes of research: (1) textual philology (including classical and biblical studies, oriental literatures such as those in Sanskrit and Arabic, and medieval and modern European writings); (2) theories of the origin and nature of language; and (3) comparative study of the structures and historical evolution of languages and of language families. This last inquiry had stunning result: the recovery of a vanished, previously unsuspected language, parent of most tongues of Europe, northern India, and the Iranian plateau.

These three wide zones of philological scholarship, diverse in subject, shared likeness in method. All three deployed a mode of research that set them apart from the other great nineteenth-century model of knowledge, Newtonian natural science. All philologists believed history to be the key to unlocking the different mysteries they sought to solve. Only by understanding the historical origins of texts, of different languages, or of language itself could a scholar adequately explain the object of study. Moreover, all breeds of philologist understood historical research as comparative in nature. Only by placing a classical text or the grammar of Sanskrit into multiple comparative contexts could a scholar adequately understand eitherby comparing the classical text with other manuscripts and with historical evidence surrounding them; by comparing Sanskrit grammar with similar Indo-European grammars (as well as, at least tacitly, dissimilar grammars of other language families). Furthermore, philologists understood history not only as comparative but also as genealogical. They aspired to find historical origins in a very specific sense of the term: to uncover lines of descent leading from an ancestral form through intermediate forms to a contemporary one. Later in this book we shall see how historicism, with its insistence on comparison and genealogy, replicated itself in the DNA of the modern humanities.

Equipped with these powerful tools of investigation, philology animated sundry types of knowledge across the academic countryside. Until the natural sciences usurped its throne in the last third of the nineteenth century, philology supplied probably the most influential model of learning.resonance of philology as a paradigm of knowledge is much less well known today than the parallel influence of natural science, because science won and philology lost. Victors often erase the footprints of the defeated. Ask any modern student of ancient Carthage.

I stumbled on some buried ruins by accident, over thirty years ago. In the early 1980s, I set out to write a life of Charles Eliot Norton. Norton was the most prolific begetter of the humanities at the time when modern American higher education was taking off, the decades after 1870. It made sense to start research for a biography with my subjects parents. The mother, Catharine Eliot Norton, left behind only scraps of correspondence. The father, Andrews Norton, a Bible scholar, supplied a lot more posthumous debris. The trove included notes for his Harvard University lectures on biblical criticism. In perusing these, I learned that a conventionalist theory of language (more about this in ) undergirded the elder Nortons understanding of the Bible and theology. He even believed that other philosophies of language threatened religious faith. In the 1830s, Andrews Norton got into a public argument with his sometime student Ralph Waldo Emerson over the latters heterodox religion. In plowing through the printed and private records of their row, I discovered that Emersons ideas about language frightened and angered Norton as much as his religious doctrines: Emersons linguistic heresy, Norton insisted, underlay his religious infidelity.

Next page