FASHION

BEYOND

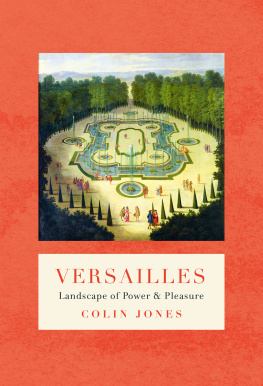

VERSAILLES

FASHION

BEYOND

VERSAILLES

CONSUMPTION AND DESIGN IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY FRANCE

DONNA J. BOHANAN

Published by Louisiana State University Press

Copyright 2012 by Louisiana State University Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing

Designer: Barbara Neely Bourgoyne

Typefaces: Arno Pro, Text; Engravers MT and Din Schrift, display

Printer: McNaughton & Gunn, Inc.

Binder: Acme Bookbinding, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bohanan, Donna, 1954

Fashion beyond Versailles : consumption and design in seventeenth-century France / Donna Bohanan.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8071-4521-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8071-4522-7 (pdf) ISBN 978-0-8071-4523-4 (epub) ISBN 978-0-8071-4524-1 (mobi) 1. FashionFranceHistory17th century. 2. NobilityFranceSocial life and customs17th century. 3. Elite (Social sciences)FranceHistory17th century. 4. Consumption (Economics)FranceHistory17th century. I. Title.

TT504.6.F7B64 2012

746.92dc23

2011043188

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

For Cynthia Ackermann-Bohanan

and

in memory of

Belinda Bohanan

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book started years ago in the archives of Grenoble, while I was there to work on a different project. I was examining a series of seventeenth-century household inventories in order to gain a sense of the wealth of noble families. These sorts of inventories, prepared by notaries at the death of a testator, have become the stock of material culture studies. I was soon captivated by the contents of these families residences; I felt as if I were the ultimate interloper, and I relished it! In reading the detailed lists and descriptions of the objects that filled noble homes, I wondered more and more about how families actually lived with their possessions, how these objects shaped their daily lives, and how they used them to define themselves. And so this book began in the archives and with the inventories; only later did I set out in search of the literature to help me understand my documents. I am indebted to the staffs of the Archives Dpartementales de lIsre and the Bibliothque Municipale de Grenoble.

Back in the United States, the production of this project benefited enormously from the support of Auburn University, in particular the History Department. My department chairs, Bill Trimble, Tony Carey, and Charles Israel, arranged my schedule to give me time in the archives and allow for blocks of time in which to write. My cherished colleagues, Daniel Szechi and Ralph Kingston, listened cheerfully and never failed to offer invaluable suggestions. Christopher Ferguson was a gold mine of bibliographic suggestions, especially pertaining to early modern Britain. Joseph Kicklighter was, as always, my stalwart mentor and friend.

I also want to thank my acquisitions editor at LSU Press, Alisa Plant. I first met her at a meeting of the Southern Historical Association in Birmingham, Alabama. She was quick to express real interest in the project and never gave up on it or me, this despite my innumerable delays and pleadings for extra time. Teresa Rodriguez cheerfully worked with little notice to produce her inspired interpretations of period furnishings. They are wonderful. And I am indebted to my copy editor, Grace Carino, who painstakingly corrected and edited my manuscript.

Finally, much gratitude goes to those who were there day in and day out, my family. My parents, Donald and Jean Bohanan, have always supported me in every way they can, not the least of which is reminding me of my deadlines and my tragic tendency to procrastinate! My sister and brother-in-law, Cindy and Paul Ackermann, took me into their Swiss home weekend after weekend and sent me renewed and reenergized on Sunday evenings back to the archives in Grenoble.

I owe no greater debt than to Frank Smith, my husband, who held down the fort and took care of Sutyi, Axel, and Nola while I was absent from home for long periods. As always, he proofread and edited this manuscript in his incisive and dramatic manner.

Finally, my sisters, Cindy and Lindy, inspired this project. From Arkansas to Switzerland, in brocantes, flea markets, and antique shows, they revealed to me the thrill of the hunt. This book is for them.

FASHION

BEYOND

VERSAILLES

INTRODUCTION

This is a book about things. By things, I mean the possessions that accumulate during a lifetime and, at death, are inventoried and dispersed to heirs. In a sense it is a book about material culture, but it is not about the actual things themselves. This is not a study of the objects; it is not a history of the decorative arts. It is social history, a book about what things can tell us about the lives and lifestyles of their owners. The larger issue is how people used their goods, why they purchased them, and what goods meant in their social worlds. I base my remarks on notarial descriptions of objects, which offer a particular observation point.

What we now know about the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries is that the demand for necessities and fashionable luxuries grew by revolutionary proportions, thereby providing a very important stimulus for economic growth and industrialization. McKendrick, Brewer, and Plumb were among the first historians of the eighteenth century to offer ample evidence for the important role of consumption in economic development, in their case British development. The households I consider were inventoried during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, roughly the period 1680 to 1715, the point at which the consumption of nonessential goods began to take off in France. These developments were the antecedents to the rise of modern consumerism.

I will argue that such rising levels of consumption had special social significance in Dauphin, a locale that had earlier endured a fiercely contested struggle over efforts to make nobles pay the detested tax known as the taille. As part of the debate over traditional tax exemptions for the nobility, the opposition mounted a rhetorical campaign challenging the nobles rights and questioning their antiquity and integrity. Royal government, by its financial policies and judicial responses to the local cases at the heart of the crisis, served as a catalyst for social conflict in the region. In the end, the conflict known as the procs des tailles was resolved in a manner that emphasized more than ever the antiquity of a family and its concurrent lifestyle. By 1680, the procs des tailles was forty years past, and I invoke its lingering memory as meaningful political context for elite patterns of consumption.

The first chapter of this book focuses on the sociopolitical world of these consumers and establishes the importance of consumption and display. To contextualize elite consumption, it considers the crisis of regional politics and changing ideas of nobilitythis in addition to cultural forces, such as the ideology of taste, that shaped nobles consumer choices. The remaining chapters are each constructed around a particular type of goods or furnishings. In discussing these, I examine their impact on the life of the owner, the potential reasons for their purchase, and what ownership and exhibition tell us about changes in aristocratic society.