Slavery, Fatherhood, and Paternal Duty in African American Communities over the Long Nineteenth Century

THE JOHN HOPE FRANKLIN SERIES IN AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY AND CULTURE

Waldo E. Martin Jr. and Patricia Sullivan, editors

Slavery, Fatherhood, and Paternal Duty in African American Communities over the Long Nineteenth Century

Libra R. Hilde

The University of North Carolina PressCHAPEL HILL

Publication of this book was supported by a grant from San Jos State University.

2020 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Set in Merope Basic by Westchester Publishing Services

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hilde, Libra Rose, author.

Title: Slavery, fatherhood, and paternal duty in African American communities over the long nineteenth century / Libra R. Hilde.

Other titles: John Hope Franklin series in African American history and culture.

Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, 2020. | Series: The John Hope Franklin series in African American history and culture | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020015444 | ISBN 9781469660660 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469660677 (paperback : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469660684 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: African AmericansFamily relationshipsUnited States History19th century. | Fatherhood. | Masculinity. | Slaves United StatesSocial conditions19th century.

Classification: LCC E185.86 .H654 2020 | DDC 973.7092/2 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020015444

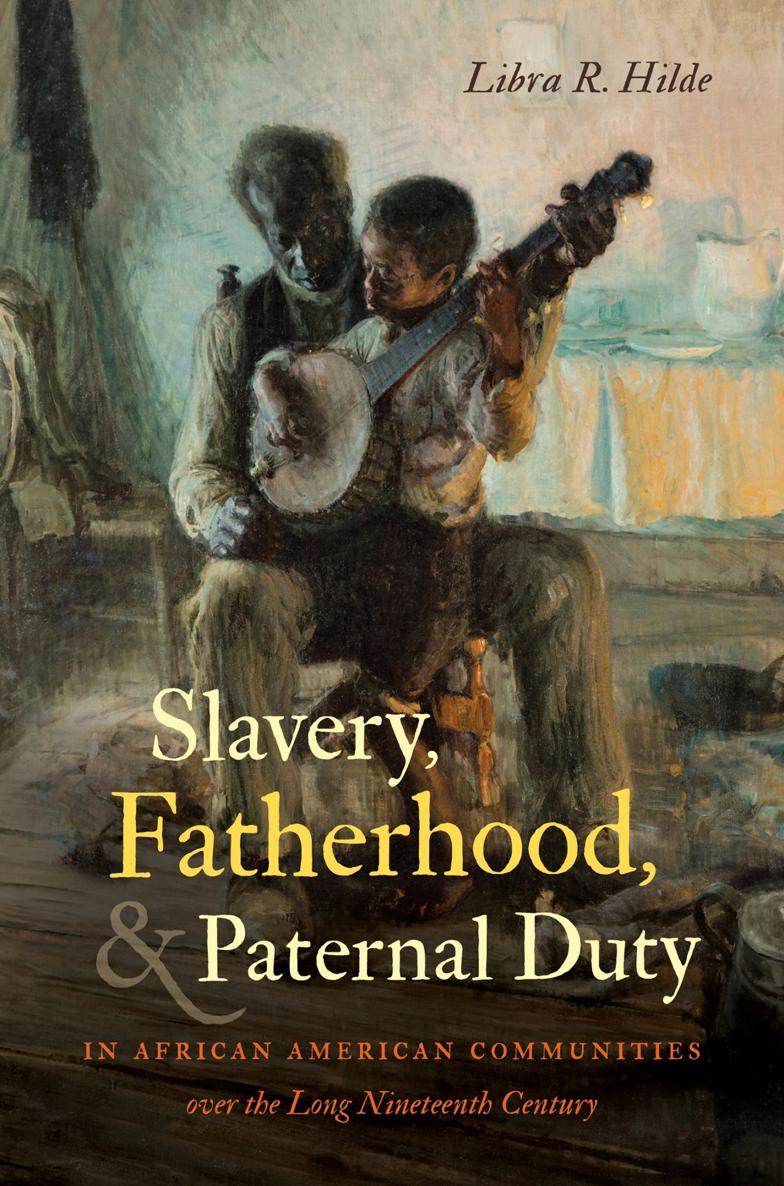

Cover illustration: Henry O. Tanner, The Banjo Lesson (1893). Collection of the Hampton University Museum, Hampton, Virginia.

Contents

Acknowledgments

This project had its genesis in the classroom. In History 100W, a required writing course for majors, I often assign a comparative paper on Harriet Jacobss Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl and Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. In semester after semester of discussions and guiding students as they crafted arguments based on these narratives, I kept coming back to the juxtaposition of Douglasss and Jacobss commentary on fatherhood. There is a stark contrast between an enslaved man who desperately wanted to parent and free his children and died unable to accomplish these goals (unaware of the ways in which he shaped the lives and motivations of his daughter) and an unknown slaveholder who took no responsibility for his mixed-race son. I owe a debt to the countless students who have come through this class, as well as the masters students who took my graduate course on slavery, as they all unwittingly contributed to the development of this book.

As the book moved from the conceptual stage to a reality, I made a common mistake and produced an unwieldy and unfocused draft. I then had the good fortune to spend the 201718 academic year on a fellowship at the Center for the Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences (CASBS) at Stanford University. In this beautiful setting, spurred by thought-provoking seminars and lunchtime conversations, I had ample time to completely rewrite the manuscript and rethink my arguments. I want to thank CASBS Director Margaret Levi and Executive Director Sally Schroeder for taking a chance on me amidst a field of applicants from research-one universities. I cannot name all forty-five fellows here, but know that spending a year up on the hill with each and every one of you shaped this book. A special shout-out is in order for Hector Postigo, Ariela Gross, and Francille Rusan Wilson for their invaluable suggestions.

I want to express my immense gratitude to Rose McDermott, a former CASBS fellow who was instrumental in convincing me to apply for and secure the fellowship, who read and commented on early iterations of two chapters, and who has been a cheerleader throughout. Id also like to thank my former student Nicole Viglini for her contributions to the evolution of two chapters, and Alana Conner and Luci Herman for their last-minute editing. Finally, this book has benefited immeasurably from the comments of the anonymous reviewers who read the manuscript more than once.

This is a book about family. Enslaved people faced tremendous burdens in forming and maintaining the family ties that were of paramount importance in their lives and informed their sense of self. Writing this book has made me hyperaware of how lucky I have been to grow up surrounded by a loving family and to have been a part of creating my own. Thank you to my four grandparents who are now gone but not forgotten, to my expansive extended family, to my extraordinary parents and sister, and to my mother-in-law. To my children, Calder and Milan, who are now both in college, you are my inspiration. And then there is the man with whom I share everything, my husband Jamie, whose imprint is all over this book. Thank you for talking me through the rough patches, for reading and commenting when I felt stuck, and most of all, for being a consummate caretaker.

Slavery, Fatherhood, and Paternal Duty in African American Communities over the Long Nineteenth Century

Introduction

My father, by his nature, as well as by the habit of transacting business as a skilful mechanic, had more of the feelings of a freeman than is common among slaves, Harriet Jacobs recalled in the opening pages of her narrative. My brother was a spirited boy; and being brought up under such influences, he early detested the name of master and mistress. One day, when his father and his mistress both happened to call him at the same time, he hesitated between the two; being perplexed to know which had the strongest claim upon his obedience. He finally concluded to go to his mistress. Jacobs described the forceful reaction of their father, Elijah Knox. You are my child and when I call you, you should come immediately, if you have to pass through fire and water. In a system engineered to deny his patriarchal rights, Elijah attempted to assert his authority. He also attempted to provide for his children materially and emotionally. As a skilled carpenter, for a time he had permission to hire his own labor and he saved his money in a futile attempt to purchase the freedom of his children. Although unable to realize this goal, he did give his two oldest children the habits of mind and force of will that led them to seek and attain liberty.

Slavery denied the enslaved control of their bodies and lives. Because slaves could be separated from their children at any time, parenting was a tenuous process. Masters appointed themselves paternalists and suppressed the rights of enslaved fathers. The denial of black manhood was central to white manhood, American nationalism, and class relations, Edward Baptist argues. African Americans were not considered men because they lacked the essential attributes of American masculinitycontrol over their own labor, property, marriages, and children. Enslaved fathers could not overtly protect their families without risking their own safety. They frequently lived on different plantations and apart from their wives and children. Despite a system designed to disempower them, however, enslaved fathers were often an influential presence in the lives of their children. Not all enslaved men could or wanted to be active fathers, but many endeavored to nurture their children in an atmosphere that was hostile to black mens open expressions of authority.