First published in Great Britain in 1974 by Martin Robertson, this edition published in 2018 by

Policy Press University of Bristol 1-9 Old Park Hill Bristol BS2 8BB UK Tel +44 (0)117 954 5940 e-mail

North American office: Policy Press c/o The University of Chicago Press 1427 East 60th Street Chicago, IL 60637, USA t: +1 773 702 7700 f: +1 773-702-9756 e:

Ann Oakley 2018

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book has been requested.

ISBN 978-1-4473-4616-6 hardcover

ISBN 978-1-4473-4943-3 ePub

ISBN 978-1-4473-4944-0 Mobi

ISBN 978-1-4473-4941-9 ePdf

The right of Ann Oakley to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the 1988 Copyright, Designs and Patents Act.

All rights reserved: no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission of Policy Press.

The statements and opinions contained within this publication are solely those of the author and not of The University of Bristol or Policy Press. The University of Bristol and Policy Press disclaim responsibility for any injury to persons or property resulting from any material published in this publication.

Policy Press works to counter discrimination on grounds of gender, race, disability, age and sexuality.

Cover design by blu inc, Bristol

Front cover: image kindly supplied by istock

Readers Guide

This book has been optimised for PDA.

Tables may have been presented to accommodate this devices limitations.

Image presentation is limited by this devices limitations.

What began life as an academic doctoral thesis ended up being probably the most influential of all my books. The birth, gestation and delivery of The Sociology of Housework are described in detail elsewhere but the summary version is as follows: in 1967-9 I found myself performing the customary occupation of many women throughout the world, looking after small children and a home. The children were wonderful (the home less so) but I had become seriously irked by the social isolation and under-valuation of this role, which was especially a shock to those of us women who had benefitted from the 1960s expansion of higher education in the UK, and had absorbed as a result the deeply erroneous idea that from henceforward all doors would be open to us, just as they were for men. Children and housework closed those doors, it seemed. Having studied philosophy, logic, politics, economics and sociology at university, I thought perhaps it would be worth applying those frameworks of understanding to the subject of domestic labour. It proved difficult to find an academic home and a doctoral supervisor for my idea, and publishing houses were similarly unreceptive when I turned the completed research into a detailed narrative, not only of what the women I interviewed for the project actually said about housework, but of how women, historically, had been manoeuvred into this position of doing the worlds dirty work.

The difficulties of getting a supervisor and a publisher are, of course, intimately connected to the topic itself. How could housework possibly be a serious academic subject? Who would want to spend good money on buying a book about it? The unexpected career of The Sociology of Housework owed much to the political and intellectual climate of the 1970s, which was populated by some people who considered that the time was overdue for a re-evaluation of housework and, indeed, of the whole awkward subject of women and gender.

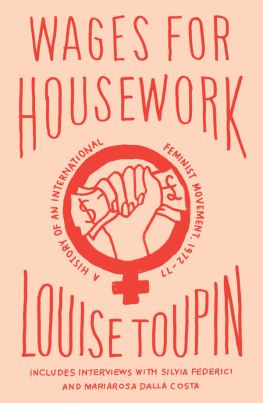

The Sociology of Housework opens with an ingenuously spirited attack on the treatment of women in sociology and the gender-blindness of its founding fathers. I wrote this at the suggestion of the publisher I eventually found for the book, who probably had more of an eye than I did then on the way in which the sociology of domestic work was about to benefit exponentially from the increased public and academic interest in gender. Chapter 1 of the book, The invisible woman: sexism in sociology argues that women feature in sociology as ghosts, shadows or stereotyped characters, a condition achieved through sexist bias in the classification of subject-areas, the definition of concepts, research topics and methods, and the construction of models and theories. Generic invisibility was matched by over-visibility in family sociology, but the portrayals of women here reflected other peoples theories about them, rather than their own experiences. Hence, womens actual work in the home was concealed behind a veil of suppositions about their roles as heterosexual wives and mothers, and it was these suppositions which also gave rise to that curious cultural phenomenon of the working mother a term meaning the mother who gets paid for employment outside the home, as though the work women do inside it without pay simply doesnt count.

Which, of course, it doesnt: it didnt, in the early 1970s when The Sociology of Housework was written, and it doesnt now, in 2018. Internationally agreed systems for producing national accounts exclude unpaid domestic work; they relegate it to something called a household satellite account. The grounds recited in the official guidelines for treating housework thus are unconvincingly spurious: that no-one can measure housework because it is possible for somebody to prepare a meal, keep an eye on a small child and help an older child with their homework all at the same time; housework, moreover, may overlap with leisure activity; and the only sensible way to attach a monetary value to housework is by counting what it would cost in the marketplace, which would make it simply too important as a component of the GNP.

Many of the women interviewed for my housework project were surprised that an academic researcher was taking housework seriously. The phrase just a housewife was in common currency in the 1970s as an easy way of denigrating what many (75%) of them spent more than 70 hours a week doing. Asked to describe themselves by completing a task called the Ten Statements Test, half the sample recorded I am a housewife in the first two places. Combined with their awareness of the low social value attached to housework, this was sometimes a source of uncomfortable dissonance. Pursuing my original aim of studying housework as work, I wanted to know how women handled this dissonance, and how they managed to make sense of housework as an occupation. In the pages of The Sociology of Housework I am clearly determined to understand the intersections between female socialization, self-concept, and attitudes to housework, and particularly to look at how social class affected these intersections. No-one, surely, would study housework in such a manner now. But it made sense at the time, when sociologists worried a lot about class and the dissatisfactions of domesticity were widely seen to be a function of education. Like slaves, oppressed women ought to be happy: thus, so the logic went, emancipation is to blame for the housewifes dissatisfaction.

The term housewife as self-description is not offered so much now, although there is a problem about what to replace it with SAHM (stay-at-home-mum) hardly seems accurate enough. Housewife is a more general text which reproduces four lengthy interviews from the research, and packages these with historical, sociological, anthropological and political reflections, all behind the glowing faade of a bright Omo soap powder advert. Washing and dishwashing machines were not much in evidence among the housewives I had interviewed, and a good deal of washing, including of nappies (there were no disposable nappies in the early 1970s) was done by hand. Hot water did not always come out of a tap; central heating was an uncommon luxury; some homes lacked inside lavatories; and only 5 of the 40 women had access to a car. These features of the womens situation made their housework harder, but did not stop them from creating often elaborate standards and routines for the doing of housework, some of which (for example, the fortnightly washing of all curtains, see p. 103) I recall deciding put my own housewifely efforts to shame.