CONTENTS

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk

HarperCollinsPublishers

Macken House

39/40 Mayor Street Upper

Dublin 1, D01 C9W8

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2023

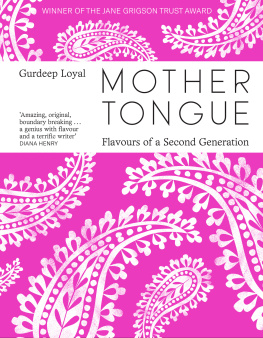

Text Gurdeep Loyal 2023

Photographs Jacqueline Walker 2023

Designed by Evi-O.Studio

Always follow the manufacturer's instructions when using kitchen appliances and other electrical tools and equipment.

Gurdeep Loyal asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Jacqueline Walker asserts the moral right to be identified as the photographer of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008464547

Ebook edition March 2023 ISBN: 9780008464554

Version: 2023-01-19

For mothers, especially my own

,

Tradition is not the worship of ashes, but the preservation of fire.

Gustav Mahler

Excuse me waiter, please can we have some chilli sauce, black pepper and English mustard?

Bhupinder Loyal, aka Mum

Contents

The irony of writing a book called Mother Tongue in a language that my own mum wont be able to fully read is not lost on me. Yet whats missing in her understanding of what these words say is countered by her fluency in the flavours, something that words can barely begin to convey.

Because my culinary palate is rooted to my mothers tongue, and hers to her mother before her; an intergenerational lineage of love that crosses continents, connecting the past to the present through taste.

Nevertheless, the food that has passed along from generation to generation migrating from India to England and a connecting hyphen-of-places in between has not remained static along its journey through time and different lands. Far from a fossilised cuisine preserved in aspic, my food inheritance has been an ever-evolving musical score of flavour, a modulating manuscript of taste scribbled over by each new generation, never deleting what came before, but always leaving edible echoes of the past on the plates of the present.

With each era, new chords of flavour have enriched the hereditary palate, as ever more relatives have added a tuneful taste of who they were. Each masala-ed imprint reveals enduring stories of individual loves and losses, toils and travels, follies and fortunes, bestowing new layers of delicious harmony on the generations that follow.

By means of this continual adaptation, the cookery handed down through maternal fingertips has transformed at each fork of the family tree. Today, it is rooted as much to its legacy trail of uprooting as it is to the soil of Punjab: my ancestral motherland and origin of my epicurean mother tongue.

I am a second generation British Indian food writer and home cook, a descendant of Punjabi farmers and Leicester market traders with big appetites, born in the early 1980s right in the very middle of Old Blighty. My paternal grandparents were the pioneers, migrating from the sugarcane fields of Punjab, via Kenya where my dad was born, to England in the late 1960s.

While the history of outward Punjabi migration dates to before the 19th century, the butterfly effects of Indian independence impelled the relocation for my own Mama and Dhadi-Ji. Indias emancipation from British rule ripped the state of Punjab in two, through a bloodstained partition that led to the murder of millions and one of the largest mass migrations across borders in recorded human history. Furthermore, the British Nationality Act of 1948 gave all Commonwealth citizens a right to move to a battered post-war Britain. Consequently, it was to Leicester that many displaced Punjabis travelled a manufacturing hub for textiles, biscuits and crisps which in decades to follow would become the first British city with a majority non-white population.

My parents married in Leicester in 1981. Mum a stylish 19-year-old at the time, with kohl-lined eyes and only a handful of English words arrived from Mehliana in Punjab just a few weeks before the big day. It was her first venture outside India. Meeting for the first time just weeks before their wedding, the pair were bonded for life through a connecting Aunty-Ji who acted as their bachoolah , or matrimonial fixer. To be the bachoolah for any Punjabi couple is a terrific honour. Indeed, for some in our community its their fulltime preoccupation, and this brilliant coterie of wedding-mensch really are a force to be reckoned with: their Falstaffian presence always known, their gossiping proudly indiscreet and their elaborate matchmaking the dramatic epicentre of any party worth being seen at. Its the destiny of most Punjabi children to be caught in their cupid-crossfire as soon as adulthood hits. In modern times, this plays out through covert photo albums of unaware nieces and nephews, presented to suitors on phone screens at a moments notice. In my parents day, it was done through Polaroid photographs slipped inside blue aerograms, scribbled with a few vital statistics: analog parent-to-parent nuptial Tinder in postal form, if you will.

Their sepia-bleached wedding video, which I still take unparalleled joy in watching, begins with their Anand Karaj ceremony in our Leicester gurdwara. My dad, spruced up in a Marks & Spencer suit and wearing a turban for the very first time, sits agitatedly on the floor next to my defiantly composed mum, a firecracker of bridal red with gleaming sequins the size of pennies.

What follows is fragmented footage of their wedding party, which in that archaic era was reserved for the groom and male guests only. This raucous sausage-fest of mostly Punjabi men is a nostalgic window into a past life; the afro haircuts, flared hemlines and retro bhangra dancing preserving a revelry that lies somewhere in the Venn diagram overlap where Bend It Like Beckham meets an Abba tribute concert.

But its the food on the trestle tables of that party which took place two years before I existed and conjoined my parents in a loving marriage thats still flourishing more than forty years later that I find myself thinking about at weddings today. Paper plates filled with keema samosas, chilli fish pakoras, spicy cholay with piles of fried puris, tamarind chutney, syrup-swirled jalebi, fudgey cardamom burfi and Johnnie Walker whisky. Its the celebratory feasting of uprooted Punjabi migrants, voyaged from the motherland to their newly adopted home.

This is the flavour-punch of food that I grew up eating and to which my palate is deeply rooted. Yet from an early age my greedy stomach was also seeking out something else; because like all second generationers around the world (and indeed like any first generationers raised away from their native cradle), my British Indian existence, by birth, was the hybrid kind.

Outwardly, my cinnamon-brown skin, almond eyes and aquiline nose mark me out as immigrant in India.