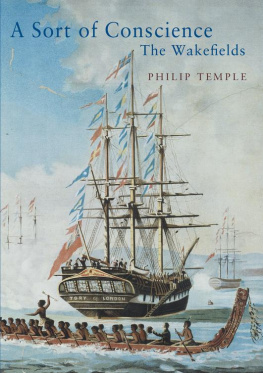

I N THE POLITICAL AND SOCIAL climate of the early twenty-first century, Edward Gibbon Wakefield and his family are the villains of all fashionable post-colonial scenarios of the past. Until about 50 years ago, Edward Gibbon was considered at least partly responsible for the British settlement of New Zealand, his brothers and son its active agents and its occurrence essentially a good thing. Wakefield also played a seminal role in the shaping of British colonial policy over two decades from the early 1830s, had a direct influence on the settlement of South Australia and assisted in the creation of a Canadian constitution. This arguably positive work was always overshadowed by the notorious cases of fraud and abduction that had led to his earlier imprisonment. Yet many of Wakefields notable contemporaries, and historians and economists over the century following his death, were willing to look past the notoriety to his vision and political achievements.

The decline of the Wakefields in the pantheon of politically correct memory can be judged by the fact that in 1966, when some New Zealanders still thought Home was England, the New Zealand Encyclopedia listed no fewer than eight entries under the name Wakefield; by 1990, the sesquicentennial judgement of the first volume of The Dictionary of New Zealand Biography allowed only two:* Edward Gibbon, whose influence in planning New Zealands colonial settlement could not be set aside, and his son Jerningham, principally because he wrote a good book. Notably absent were William, leader of the New Zealand Companys Tory expedition in 1839 and then of the Wellington settlement, and Arthur, leader of the Nelson settlement in 1841 and killed by Te Rangihaeata in the Wairau confrontation of 1843.

This official revisionism, and the antipathy the name Wakefield often aroused, alerted me to a vein of prejudice in much educated opinion. I found also that, though there were four hagiographies of Edward Gibbon Wakefield, written in the days when he was seen as a founder of empire or commonwealth, there was no dispassionate biography of a family that played such a significant and controversial role in the establishment of the larger British colonial democracies. All of this provoked me to set out to discover just who Edward Gibbon Wakefield and his family were, where they came from and what they did. I felt that an understanding of their character and circumstances would contribute towards a better understanding of their motives and actions. It seemed a necessary and useful task, one that would assist in reaching fresh perspectives on colonial history.

As is often the case with biographical projects, this work has taken much longer than expected: I planned to complete it in three to five years, but ended only after eleven. I underestimated the time it would take to research and write about an entire family, even if one was the central figure, and to grasp the colonial, and wider, politics of the first half of the nineteenth century. Also, I became utterly absorbed in the forensics of the project: the piecing together of clues in correspondence, for example, that brought to light previously unrecorded events and actions or newly illuminated character and motive.

I experienced those transcendent moments, familiar to all historical biographers, when the author seems to touch the hand or face of their subject. When, years ago, I travelled wild country to retrace the journeys of early New Zealand explorers, this occurred with positive identification of old campsites or plants that were the holotypes for original scientific descriptions. With the Wakefields, it occurred on such occasions as taking delivery from Admiralty archives of the log of the ship Arthur commanded while chasing West African slavers in the 1820s; or when turning the pages of Eliza Wakefields diary, reading the last entries before her premature death; or when sitting in the cold parish church of Stoke-by-Nayland, where this scattered family had occasionally gathered together and where they are now forgotten save in the tilt of churchyard gravestones.

The political context was always important, especially for Edward Gibbon Wakefield from the 1830s, but I searched, too, for the people, their characters and relationships. At such a distance in time this proved difficult, for there were often considerable gaps in correspondence or journals and sometimes very little at all for William until 1839, for example, or for Felix until he returned from Tasmania to England in 1847. I did not fully grasp Edward Gibbons complex personality until I read archived correspondence in Ottawa that suddenly threw into relief the English and New Zealand material.

I cast wide in an attempt to explain behaviour and motive, paying attention to medical conditions and the effects of personal loss and grief. I wished to discover the role of women wives, sisters, daughters on Edward Gibbon Wakefield and his brothers. The influence of grandmother Priscilla had been made plain in the earlier hagiographies, but mother Susannah had always been pushed into the background. Why? Even elder sister Catherine had not been fully drawn, although so much of the surviving correspondence suggested that the book might well be titled, My Dear Catherine.

Although the focus of the book would be on Edward Gibbon Wakefield and his siblings as adults, I needed to explore fully the family circumstances that shaped them and influenced both their careers and their personal behaviour. Grandmother Priscilla and father Edward were deeply involved in reform movements of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and it seemed essential to look at the people and causes that surrounded the new generation of Wakefields as they grew up. The starting point for the narrative became obvious: Edward the fathers marriage in 1791, at a time of great political and social change, and as the eldest son of a family whose financial resources had unexpectedly contracted. In times of general upheaval there was personal upheaval; tensions both creative and destructive governed the future of a family whose reduced income could no longer adequately support the upper-middle-class status and political influence they had come to expect. They became a part of the growing uneasy classes who would turn to emigration in the great wave of British colonisation of North America and Australasia that began in the generation after the end of the Napoleonic Wars.

The chapters have been arranged in four parts that correspond to relatively distinct eras of Wakefield family history in the century after 1791. Part One covers the early years, in which all of Edward Gibbons generation reached maturity, and ends with the catastrophic fracture of the family caused by Edward Gibbons and Williams imprisonment following their abduction of Ellen Turner. Part Two spans the most active years of Edward Gibbon Wakefields writing and propaganda in the cause of planned colonial settlement, concluding with William setting out as leader of the New Zealand Company expedition. It also includes Edward Gibbons journey to Canada with Lord Durham, Williams military career in Spain and Arthurs naval career. The first half of the book is located principally in England, although Arthur takes us to the East Indies and all over the Atlantic world.

Part Three deals with the establishment of New Zealands Wellington and Nelson settlements, and the conflicts they entailed, to the points of both Arthurs and Williams deaths. Edward Gibbon Wakefields second period in Canada is included, as is Felixs life in Tasmania. The final part focuses on the development of the Canterbury settlement, Edward Gibbons and Felixs migration to New Zealand and Edward Gibbons part in early provincial and national government. It concludes with the death of all the remaining siblings of that generation and Edward Gibbons son, Jerningham.