Contents

Guide

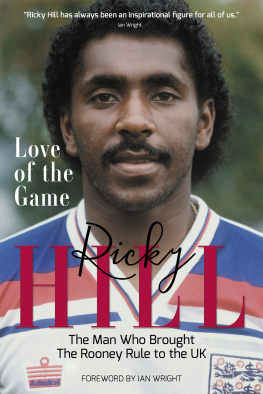

First published by Pitch Publishing, 2021

Pitch Publishing

A2 Yeoman Gate

Yeoman Way

Worthing

Sussex

BN13 3QZ

www.pitchpublishing.co.uk

2021, Ricky Hill with Adrian Durham

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright.

Any oversight will be rectified in future editions at the earliest opportunity by the publisher.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, sold or utilised in any form or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the Publisher.

A CIP catalogue record is available for this book from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78531 826 9

Typesetting and origination by Pitch Publishing

Printed and bound in India by Replika Press Pvt. Ltd.

Contents

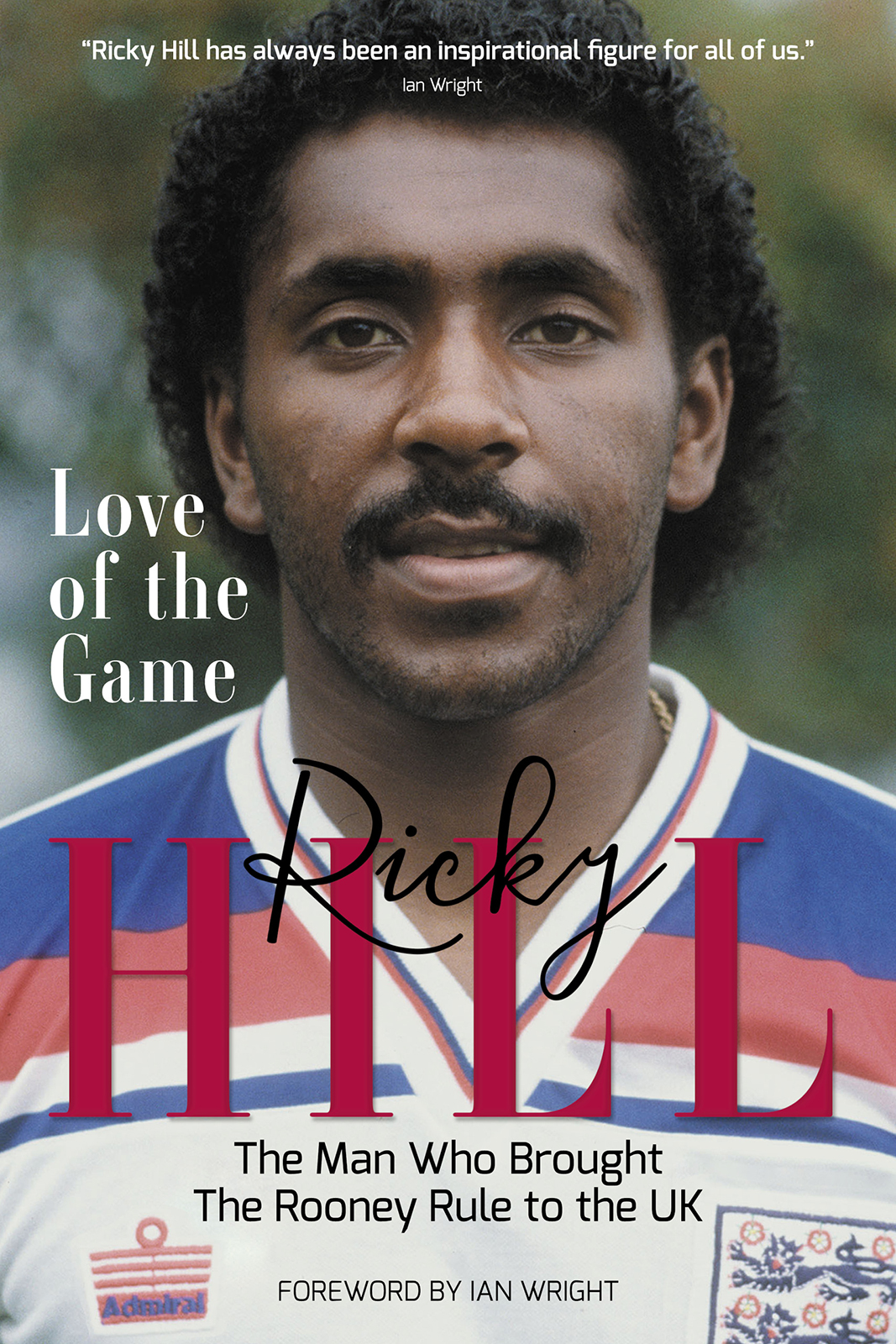

Foreword by former Arsenal and England striker Ian Wright

RICKY HILL meant a lot to me, and he still means a lot to me. He was without any question one of the pioneers. And what a footballer! He played the kind of football that black players played when me and my mates were just knocking a ball around while we were growing up. He was exciting, dynamic, he wanted to attack all the time, but he always worked so hard for the team as well. I loved his curly perm, that juicy hair, and I really loved the way he played, with that swagger in the midfield.

When Crystal Palace offered me a trial and then a contract in 1985, I was a Sunday league player with Ten-em-Bee, an all-black team in London. We played in an annual tournament and Ricky was always there, every year, watching the games, watching players, and by this time he was an established young professional at Luton. We all knew he was one of us, a black kid from London, who hadnt been picked up by a professional club as a boy but someone who had properly made it in respects of being in and around the England scene and being among the best players in the top division, and being admired by fans and people in the game. Ricky was up there at that level, but he took the time to come and see us play. It meant so much to me and everyone else.

He really doesnt get the credit he deserves for what he did as a player and what hes done to help black coaches and managers after playing. But at the same time, every black player will know that Ricky had a prominent influence on the rise of black players back in the day. Ricky Hill has always been an inspirational figure for all of us.

1

Joy and Pain of the Game

I HAVE always loved football and I still love it. From kicking a ball around outside my house in north London, to playing for England at Wembley, four miles from where I grew up, being in and around football all my life has been a joy. I was the fourth black player to represent England, after Viv Anderson, Laurie Cunningham and my schoolboy friend Cyrille Regis. I was the first British South Asian to play for England, the first of Indian origin to wear the Three Lions shirt.

Ive got a pure love of the game, but Ive also experienced the pain of the game as well.

Ive been with my amazing wife Sharon since 1982, and we have been married since 1986. Shes been the rock not just for me but also for our family, coping with move after move as I tried to build a coaching career. But despite me playing for Luton over 500 times, as well as England, she only saw me play a few matches in my entire career. Why? Because the first time she watched me she was sickened by the racist abuse I was subjected to. It was at QPR, less than three miles from where she was brought up in Kensal Rise, north London.

In this era, racial abuse of players was commonplace. Chelseas Paul Canoville was targeted by fans of the club he was playing for, and John Fashanu told me that when he scored for Millwall, large sections of their fans would call it an own goal because they could not tolerate a black player scoring for their team.

That day at Loftus Road, Brian Stein and I were the only black players on the pitch. Sharon was just 18. She took her seat and then listened to the vicious hate towards the two of us. It took all of her strength of character not to respond to the cowards. Afterwards she was adamant she would never attend another game. As I recall she only came three more times to watch me play the game I love; the two League Cup finals in the late 1980s and a league match at Luton. Thankfully she wasnt there to witness me suffering a horrible injury on the pitch in a game in 1987, and so she didnt hear the subsequent shouts of nigger, hope it ends your career raining down from the terraces.

Personally I could deal with that type of direct racial abuse. Im certainly not excusing it or saying its acceptable, but I learned to deal with it in my own way.

Its the covert racism that seems impossible to change. Its embedded in the systemic culture of all the institutions within the UK and elsewhere. That, in my opinion, is the real offensive racial discrimination as it prevents black people like me from living an equal life, with equal opportunities. Those decision-makers who freely quote if theyre good enough theyll get their chance are never then asked how, over the last 30 years, so many black or Asian minority coaches have been excluded from not just managerial opportunities, but more importantly, a chance to coach at the senior professional level in order to create a track record, and be in the conversations when managerial vacancies appear.

Just as black players found it hard to be accepted into the professional game in the 1970s, black managers years later would find that acceptance equally difficult.

It always seemed slightly strange to me. Think about it: the greatest footballer on earth was universally acknowledged to be Pele, and he just happened to be black. He took the football world by storm as long ago as the 1950s. As a boy in the 1960s, and into my teenage years in the early 1970s, in the European leagues and in particular the English leagues, black players who were attempting to carve out a career in the world of professional football were rejected and in most cases totally ignored. And along with that reaction came the stereotypical statements such as black players dont like the cold weather; black players are too volatile; black players cant head the ball. It was as if those in positions of power in football managers, coaches, chairmen and the Football Association were making a conscious effort to propel those stereotypes throughout the industry. Here is an example from 1983 in Shoot!, the most popular football magazine at the time, in an article about why black players were becoming more and more successful in that decade, Twenty years ago the chances of Cyrille [Regis] managing to bridge the gap between non-league football and the big time would have been strictly limited, probably nil. Black men did not play league football in those days. The trouble with most black footballers hoping to make a career in the British game in those days was that they bore all the physical attributes necessary to play but had glaring weaknesses in technique and attitude. They often lacked commitment, they struggled to concentrate for a full 90 minutes and tended to wilt under pressure.