The Complete Works of

ALCIPHRON

(fl. 2nd century AD)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2022

Version 1

Browse Ancient Classics

The Complete Works of

ALCIPHRON

By Delphi Classics, 2022

COPYRIGHT

Complete Works of Alciphron

First published in the United Kingdom in 2022 by Delphi Classics.

Delphi Classics, 2022.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

ISBN: 978 1 80170 049 8

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: sales@delphiclassics.com

www.delphiclassics.com

The Translations

View of Athens ancient agora. No biographical details about Alciphron have survived. The majority of his works are set in Athens or its surrounding demes, soon after the reign of Alexander the Great.

The Letters of Alciphron, 1896 Translation

LITERALLY AND COMPLETELY TRANSLATED FROM THE GREEK, WITH INTRODUCTION AND NOTES

Translated by the Athenian Society , 1896

CONTENTS

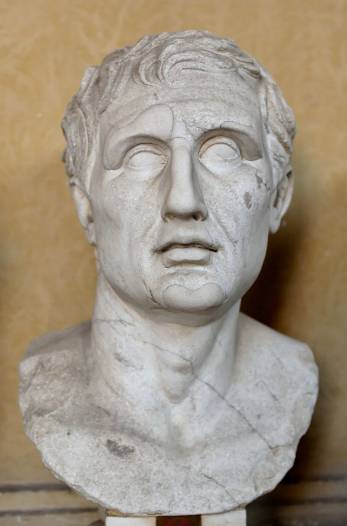

Roman bust of Menander after a Greek original (c. 300 BC) Menander was an important influence on the style of Alciphron.

INTRODUCTION

ALCIPHRON was a Greek sophist, and one of the most eminent of the Greek epistolographers. We have no direct information of any kind respecting his life or the age in which he lived. Some assign him to the fifth century A.D.; others, to the period between Lucian and Aristaenetus (170-350 A.D.); while others again are of opinion that he lived before Lucian. The only circumstance that suggests anything in regard to the period at which he lived is the fact that, amongst the letters of Aristaenetus, there are two which passed between Lucian and Alciphron; and, as Aristaenetus is generally trustworthy, we may infer that Alciphron was a contemporary of Lucian, which is not incompatible with the opinion, true or false, that he imitated him.

It cannot be proved that Alciphron, any more than Aristaenetus, was a real name. It is probable that there was a well-known sophist of that name in the second century A.D., but it does not follow that he wrote the letters.

The letters, as we have them, are divided into three books. Their object is to delineate the characters of certain classes of persons by introducing them as expressing their peculiar sentiments and opinions upon subject with which they are familiar. For this purpose Alciphron chose country people, fishermen, parasites, and courtesans. All are made to express themselves in most elegant and graceful language, even where the subjects are low and obscene. The characters are thus to some extent raised above the ordinary standard, without any great violence being done to the truth of the reality. The form of these letters is very beautiful, and the language in which they are written is the purest Attic. The scene is, with few exceptions, Athens and its neighbourhood; the time, some period after the reign of Alexander the Great, as is clear from the letters of the second book. The New Attic comedy was the chief source from which Alciphron derived his material, and the letters contain much valuable information in regard to the characters and manners he describes, and the private life of the Athenians. We come across some remarkably modern touches, as the thimble-rigger at the fair and the claquers at the theatre. Alciphron perhaps imitated Lucian in style; but the spirit in which he treats his subjects is very different, and far more refined.

In the great majority of cases the names in the headings of the letters, which seem very clumsy in an English dress, are fictitious, and are purposely coined to express some characteristic of the persons between whom they are supposed to pass.

In the volume of Lucian in this series some account has been given of the courtesans of Athens. It will here be interesting to describe briefly another curious class of personages, the parasites a word which has had a remarkable history.

Originally, amongst the Greeks, the parasites were persons who held special functions. They had a right, like the priests, to a certain portion of the sacrificial victims, and their particular duty was to look after the storage and keep of the sacred corn, hence their name. They enjoyed an honourable position, and the Athenians resigned to them even the management of the temples, which gave them rank next to the priests.

Soon, after the example of Apollo, the richest citizens looked out for witty table-companions, to amuse them with jests, and flatter them in proportion to their importance and liberality. By degrees, however, these parasites, lending themselves to ridicule, fell into discredit and contempt. The name, diverted from its etymological signification, was applied to every haunter of the tables of the rich, to every sponger for a free meal, to every shameless flatterer who, in order to satisfy the needs of his stomach, consented to divert the company and patiently endure the insults which it pleased the master of the house to heap upon him.

At first this was by no means the case with all parasites. Gaiety, audacity, liveliness, good humour, a knowledge of the culinary art, and sometimes even a certain amount of independence lent an additional charm to the members of the profession. One of the most famous of parasites was Philoxenus of Leucas, of whom we read in Athenaeus. It was his practice, whether at home or abroad, after he had been to the bath, to go round the houses of the principal citizens, followed by boys carrying in a basket oil, vinegar, fish-sauce, and other condiments. After he had made his choice, Philoxenus, who was a great gourmand, entered without ceremony, took his seat at table, and did honour to the repast before him. One day, at Ephesus, finding that there was nothing left in the market, he asked the reason. Being told that everything had been bought up for a wedding festival, he washed and dressed himself, and deliberately walked to the house of the bridegroom, by whom he was well received. He took his seat at table, ate, drank, sang an epithalamium or marriage-song, and delighted the guests. I hope you will dine here to-morrow, said the host. Yes, answered Philoxenus, if you lay violent hands upon the market as you have done to-day. I wish I had a cranes neck, he sometimes exclaimed; then I should be able to relish the flavour of the food for a longer time. Dionysius, the tyrant of Syracuse, who knew that he was very fond of fish, invited him to dinner, and, while an enormous mullet was set before himself, sent his guest a very small one. Without being in the least disconcerted, Philoxenus took up the small fry, pretended to speak to it, and put it close to his ear, as if to hear its reply. Well, said Dionysius, somewhat annoyed, what is the matter? I was asking him certain information about the sea which interests me; but he has been caught too young: this is his excuse for having nothing to tell me. The fish in front of you, on the contrary, is old enough to satisfy my curiosity. Dionysius, pleased with the rejoinder, sent on to him his own fish. To perpetuate his memory, Philoxenus composed a Manual of Gastronomy, which was held in great repute.

Next page