An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

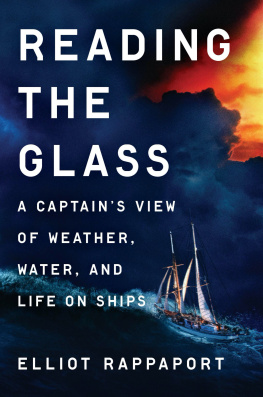

Copyright 2023 by Elliot Rappaport

Penguin Random House supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

DUTTON and the D colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Illustrations by Matthew Twombly

library of congress cataloging-in-publication data

has been applied for.

ISBN 9780593185056 (hardcover)

ISBN 9780593185070 (ebook)

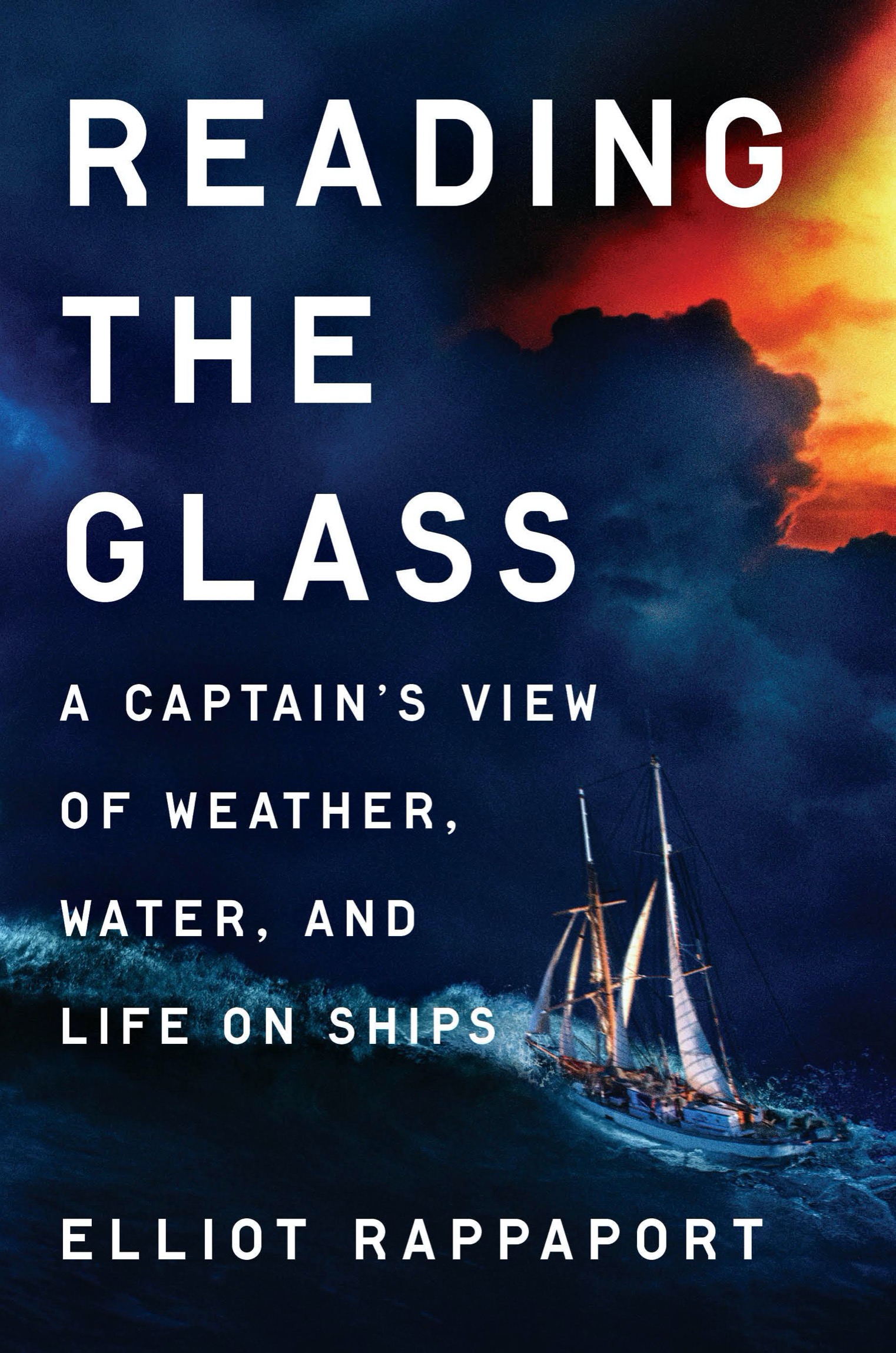

Cover design by Christopher Lin; ship photo courtesy of Sea Education Association (SEA), Woods Hole, MA

book design by tiffany estreicher, adapted for ebook by estelle malmed

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

pid_prh_6.0_142466313_c0_r0

To Karen

CONTENTS

_142466313_

Where is your ancient courage? You were used

To say that extremity was the trier of spirits;

That common chances common men could bear;

That when the sea was calm, all boats alike

Showed mastership in floating.

Coriolanus, Act 4, Scene 1

0

DAVIS STRAIT

1994

There is no night in arctic summer, just a diffuse cold glow that struggles up from underneath the horizon and dissolves slowly into the sky, the sea surface black and laced with mist like exhalations from a chest freezer. At 0215 the third mate, wearing enough clothes for a walk in space, comes below with an update on the weather. We were flying along like a gull when I went to bed. Now the wind, steady from the southwest for the last twenty-four hours, is getting light and starting to veer. The barometer has plummeted from 1016 to 994 millibars and seems to be reaching bottom. It suddenly feels like a good time to shorten sail. As the next watch comes on deck, we put the extra hands to work and reduce our canvas by about halfto one small headsail, the foresail, and a storm trysail.

The breeze quits with a final sigh, and the air turns sharply cold. The off-going watch finishes their work, waves an insincere farewell, and departs to their bunks. A gentle wind begins from the north. An hour later it is blowing a gale. We strike the foresail. The storm trysail blows out at its clew fitting, threshing angrily back and forth across the quarterdeck until we take it down also. By breakfast there are gusts to force 10storm strengthdriving a cold spray of water like birdshot across the open deck.

It is pointless now to think of making progress. We start the engine and run it slowly ahead to avoid being blown too far back the way weve just come. I have the helm put to windward, and between thrust from the propeller and the balancing force from our one remaining sail our little schooner sits like a merganser, rising and falling through an arc of thirty feet with the developing seas just ahead of the beam. Under a vague brightening in the sky, the water turns from black to gray, stirred into white streaks by the gale. The air temperature is 38 degrees Fahrenheit, just slightly colder than the seawater. The wind howls. It is hard to keep your eyes open and I wish for a swim mask.

The sea has built steeply with the reversal in wind direction, and tall green waves rear over the deck and slide below us as the boat heaves up and down. We sink into the trough. The next sea stands up vertically alongside us, a deep pane of aquarium glass. I look in and glimpse sudden dark shapes moving behinda pod of pilot whales, jet-black two-ton mammals swimming toward me, right at eye level. I dive for cover. The boat rides up the crest and the animals break the surface where wed just been, as though they are performing at SeaWorld. In unison they cut a neat arc through the air and vanish under the stern.

It is time for coffee. We have lifelines rigged around the deck, wrestling-ring style, to keep people away from the rail. I carom forward to the galley hatch and time the motion so as to fall through as gracefully as possible. Down below, it is startlingly quiet. The crew are asleep in their bunks, wedged in behind improvised pillows of spare gear. There is one person upright at the cabin table, pensively eating a Snickers bar and staring into the middle distance. Bob is our doctor, a semiretired and much beloved family physician from the small coastal town where I live in Maine. He looks a little like the actor Burt Lancaster. Ive learned that he was a PT boat officer in the Pacific before medical school and has missed being at sea for most of his life since. I am under strict instructions to bring him home alive.

I find a clean mug and fill it from the thermos, pausing to wonder just how Ive gotten myself into this situation. A good question. Professional sailors are a bit like commercial pilotslicensed operators in the transportation industry, with credentials built from a blend of hands-on experience and regulatory vetting. This said, seafaring in the jet age is a rarer and less visible career path, particularly for Americans. Most of my college friends were off to jobs in law, medicine, or academia. Uninterested in such things, Id set out sailing until an avocation became a profession, and now here I wasresponsible for an old wooden ship and sixteen souls as the cold rain blew sideways and the sea built into steep gray ridgelines around us.

It turns out that there is still nothing like a sailing ship to help you care about the weather. Motor vessels dont need the wind to take them where they are going, though their crews still recognize that weather at its extremes can take over their plans. For any who choose the more quixotic means of sail transport, the weather is everything. Understanding the weather means getting successfully to where you are going and knowing when not to try. At the least, knowledge adds a dimension of clarity to the miserable days spent amid conditions you can do nothing about.

Complex as the outcomes may be, the drivers of weather are built around a small core of scientific principles: The atmosphere is a mixture of gases subject to heating at different rates by solar radiation, governed by the physical laws uniting temperature and pressure. Weather is just atmospheric stirring, a three-dimensional cycle that solves imbalances by redistributing energy around the globe. This mixing is torqued by the rotational momentum of Earth and coupled with a water cycle that carries heat and moisture endlessly from place to place. Scientists have understood this qualitatively for some time, but it is really only in the modern era of data-gatheringthe age of aircraft, satellites, and supercomputersthat a real-time imaging of atmospheric processes has become possible.