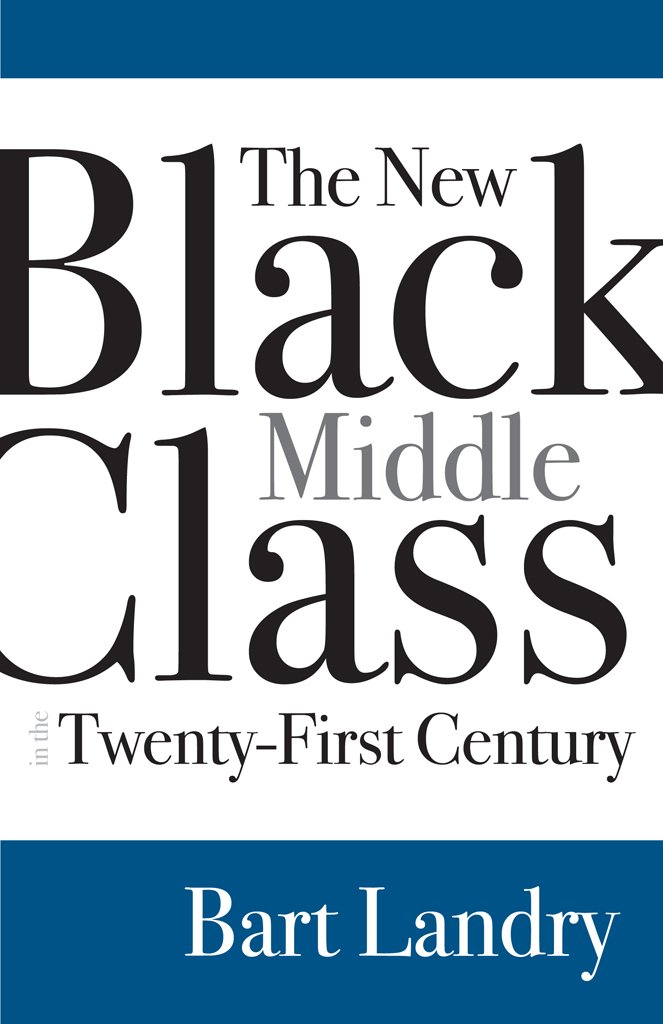

The New Black Middle Class in the Twenty-First Century, Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Number: 2017055379

A British Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the British Library.

Copyright 2018 by Bart Landry

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Please contact Rutgers University Press, 106 Somerset Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901. The only exception to this prohibition is fair use as defined by U.S. copyright law.

The paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

www.rutgersuniversitypress.org

Manufactured in the United States of America

It has been thirty years since I published The New Black Middle Class , in which I distinguished between an old black middle class and a new black middle class. The former had risen in a segregated era to serve the unmet needs of the black community in health care, education, and law. The latter emerged only after passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which banned discrimination in education and the labor force. With access to all colleges and universities, black graduates could enter a broader range of professional, managerial, and other white-collar occupations, creating a new black middle class. It was a new black middle class also because its members now had access to previously barred institutions of society: restaurants, parks, beaches, hotels, and transportation. While there had been discrimination in the North before 1964, it was especially in the South, where most blacks still lived, that the civil rights legislation had its greatest and most visible impact. College-educated middle-class blacks no longer faced the indignities of having to use Colored Only bathrooms, water fountains, and buses. Implementation of the law was sometimes slow, as when I was directed to a Colored Only bathroom during a stop for gas at a small town in Georgia in 1966. Nevertheless, change had come to the South, and the black middle class now lived in a new environment with greatly improved life chances. For the most part, they could spend their money where and how they pleased.

In defining the black middle class I follow the approach of Max Weber, who thought of class in terms of position in the economy. Their agreement ended there, however. Writing at a time in the early twentieth century when corporations were creating large numbers of white-collar jobs, Weber recognized the emergence of a new class, one that occupied a place between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. One can further distinguish between an upper middle class of professionals and administrators/executives and a lower middle class of workers in technical, sales, and clerical positions. From Webers perspective, the compensation (salary and benefits) attached to jobs in the labor market determines ones standard of living. The newly created middle class was distinguished by its higher compensationin comparison with that of manual workers compensationswhich translated into a superior standard of living.

One sometimes encounters articles announcing the decline of the middle class. The authors are typically economists who use income categories (quintiles) rather than occupation to define class. Incomes, they note, have declined or stagnated for many white-collar workers. This may erode living standards but does not mean that those individuals have dropped out of the middle class. An engineer with a lower or stagnant salary is still an engineer. Membership in a class is dependent on ownership or occupation, not level of income.

The emergence of a new black middle class was not without its challenges. Change, especially radical change in society, rarely unfolds smoothly. Sensitivity to this fact led Congress to create the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) in 1965 to administer and enforce the new law against employment discrimination. The EEOC was a place where individuals could go for redress in cases of discrimination in hiring and disparate treatment in compensation and promotion. With a greatly enlarged mandate beyond discrimination in the workplace, the commission continues to this day.

The New Black Middle Class appeared when academic scholars and policy experts were still primarily focused on the black poor. To some extent, this was understandable. In 1970, only 13 percent of employed blacks held middle-class jobs, up from only 10 percent in 1960. Poverty research had become an academic cottage industry that produced a voluminous literature on every aspect of poverty. These studies inadvertently helped stigmatize blacks as a community of poor people rather than one with a class hierarchy similar to that of whites. I wrote The New Black Middle Class to dispel this stereotype. Although small, there was a black middle class composed of an upper stratum of professionals and administrators and a lower stratum of technical, sales, and clerical white-collar workers. There was also a large working class. The relative proportions of blacks and whites in each class differed markedly (more whites in the middle class and more blacks in the working class); yet African Americans did have a class structure similar to whites. Equally importantand not surprising given the historical experiences of blacksI found great disparities in educational, occupational, income, and wealth attainment between the black and white middle classes. Still, The New Black Middle Class firmly established the existence of a black middle class in the United States. This new black middle class has continued to grow over the decades. Following the Weberian approach in defining class by occupation, the black and white middle classes, composed of white-collar workers (professionals, executives/administrators, and technical, clerical, and sales workers) were approximately 52 and 63 percent of their respective labor forces in 2010 (see Appendix). The middle class is divided into upper and lower strata, with the upper middle class composed of professionals and executives/administrators; while technical, clerical, and sales workers form the lower middle class. The gap between the black and white upper middle classes has remained roughly the same, as both have grown significantly since 1983.

The New Black Middle Class was not the first book on the black middle class, but it was the first to use national representative data. E. Franklin Fraziers Black Bourgeoisie , published in 1957, was an important book that raised many questions about the black middle class. We examined approximately ninety-four books and articles, which were divided into thirteen topics covering both historical and contemporary issues.

The paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.