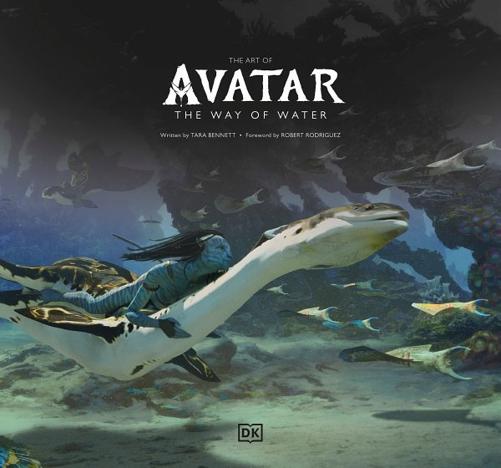

FOREWORD

I t was April 2007 and I was visiting my friend Jim Cameron at his soundstages for the first Avatar . He was shooting performance capture sequences of the mountain banshee training scenes with Zoe Saldana and Sam Worthington.

It was thrilling to see Jim yet again creating cutting-edge cinema. During a break, he walked me over to a wall filled with Avatar concept paintings.

I asked what level of detail he thought would even be possible by the time the film was released, which was still two and a half years away.

He pointed to some artwork he had pinned up and the detail was stunning. It was photoreal, like something youd see in National Geographic , but it was a single still frame concept image that his incredible artists had poured everything into.

The trick was to make an entire movie look that way. Jim said, Well, itll be interesting to see just how close to this we can get.

That blew me away, that they were forging forward in realizing such game-changing imagery while still building the technology. But Jim was always a gambler, and this was his zone.

When I started working on Alita: Battle Angel with Jim, he was neck deep in that same creative process for The Way of Water . His squad of artists had taken every learned experience, every idea, every bit of inspiration that could be gleaned from the world and poured it onto the page to create art that rivaledif not surpassedwhat I saw in 2007.

Now having seen The Way of the Water , it was personally gratifying to see, on screen, just how beautifully detailed concept art images can be realized in full motion, at a photoreal level, for an entire film.

I wasnt sure it would ever be possible.

Jim has pushed technology all these years to step up its game, and visual effects have finally caught up to the vision of Jim and his preeminent team of artists, costume designers, craftspeople, and creators.

Through Alita , Ive personally had the pleasure of working with a lot of the same artists Jim surrounded himself with to develop Avatar: The Way of Water , and they are truly world-class visionaries. They are the best of the best, and their art is what aligns all the departments on a movie of this size and scope to a common goal.

What you see on the following pages is the visual roadmap that inspires and fuels the extended dream that the film becomes.

Robert Rodriguez

Filmmaker

Jake and Neytiri date night concept | Dylan Cole

Loak swims with Payakan | Dylan Cole

Lagoon overlook concept | Dylan Cole

Lagoon underwater concept | Dylan Cole

Reef village wide concept | Steven Messing

SeaDragon arrives at a Taunui village | Ben Procter, Fausto De Martini

Kiri lying in the forest concept | Saiful Haque

g

Pregnant Neytiri bowfishing concept | Steven Messing

PROLOGUE

g

I n 2009, inside darkened movie theaters around the globe, James Cameron transported audiences to 2154, where he introduced them to the bespoke, bioluminescent, science-fiction world of Pandora in Avatar . The response was immediate and exuberant. The movie quickly became a global phenomenon, setting the stage for Camerons expanding vision.

Crafted using groundbreaking 3D visual effects, Avatar was the result of 15 years of development, world-building, and innovative cinematic technology shepherded by Cameron and his longtime producer, Jon Landau. For Camerons seventh film as director, he and Landau were aided by phenomenal teams of artists, craftspeople, and technicians who helped bring Pandora to life. The films setting and story, distilled from a lifetime of Camerons ideas and inspirations, were realized through the lens of his life experiences and his 30 years of moviemaking. At the end of its theatrical run, Avatar earned $2.7 billion worldwide, shattering the global box-office record. Compelled to tell more stories in the world with the characters of Avatar , Cameron and Fox announced in 2010 their intention to make sequels.

The first decision Cameron needed to tackle was to assess his treasure trove of story ideas and pick one that would drive the first sequel. Secondly, he needed to decide if the ongoing stories would take place exclusively on Pandora, the already-introduced moon orbiting Polyphemus, a fictional gas giant in the Alpha Centauri star system. And if not, should the new movies consider going to different planets?

Cameron and team wrestled with that conundrum very early in the creative process. We have always viewed Avatar as a metaphor for the world in which we live, Landau says in reference to Earth. We realized that we could traverse our world and not see all the wonders this planet holds. This idea helped lead Jim to the conclusion to not venture to other alien planets in the sequels, but to instead explore the diversity of locations and cultures that Pandora could still offer. Front and center of those biomes were the oceans, which reflect a passion for preservation and conservation that Jim and I share.

The commitment to remain on Pandora meant the sequels could reveal the previously unseen topography of the moon. Even without a script ready at the time preproduction began, that alone posed a massive design undertaking. Could the filmmakers create brand-new aquatic landscapes that would rival the majesty of the exotic Pandoran rain forests already seen in the first film? The design challenges and the number of elements we needed to generate proved to be an incredible, immense task, especially across four movies, says Landau. As such, work needed to start immediately.