American Jewish Civilization Series

Editors

M OSES R ISCHIN

San Francisco State University

J ONATHAN D. S ARNA

Brandeis University

All material in this work, except as identified below, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/.

All material not licensed under a Creative Commons license is all rights reserved. Permission must be obtained from the copyright owner to use this material.

Copyright 1997 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Paperback edition published 2001 by Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48201.

The publication of this volume in a freely accessible digital format has been made possible by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Mellon Foundation through their Humanities Open Book Program.

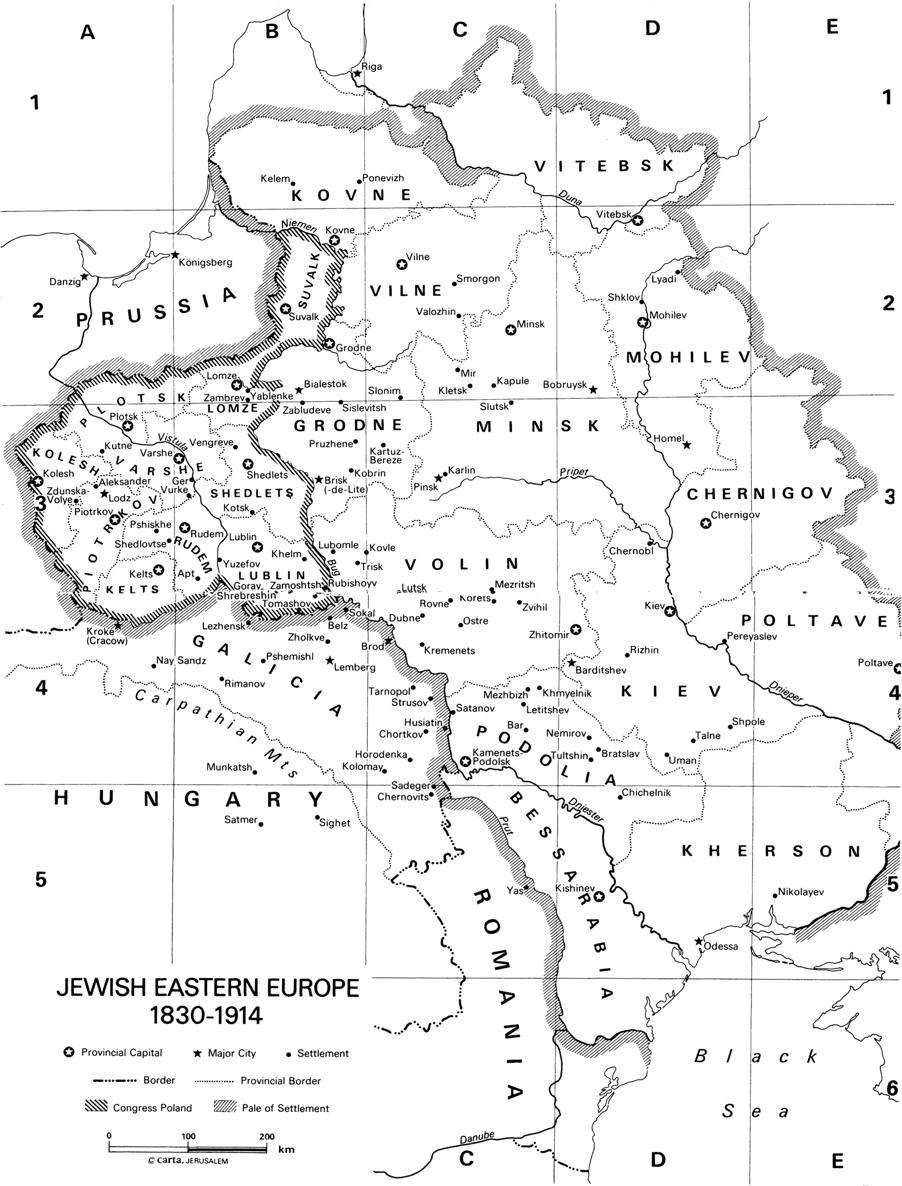

The map on pp. xxi is copyright by Carta, The Israel Map and Publishing Company Ltd. All rights reserved.

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-8143-4450-7 (paperback); 978-0-8143-4451-4 (ebook)

http://wsupress.wayne.edu/

Note on Orthography and Transliteration

Yiddish words, phrases, titles, and names of organizations, places, and persons have been rendered according to the transliteration scheme of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, except that no attempt has been made to standardize nonstandard orthography. Hebrew words, phrases, and titles have been transliterated according to a modified version of the ALA/LC 19481976 romanization table. Hebrew words in the text have been spelled according to their modern pronunciation, even if they are also commonly used in Yiddish. But Hebrew words that appear as integral parts of Yiddish titles or phrases are spelled as they are pronounced in Yiddish. Foreign words are italicized only the first time they appear, at which point they are explained.

European place names in the text follow the main entry in Mokotoff and Sack, Where Once We Walked: A Guide to Jewish Communities Destroyed in the Holocaust . They do not include the diacritical marks used in the original languages. Where Yiddish or other commonly used names for a location differ significantly from the main term used in another language (Brisk [Yiddish], Brzesc nad Bugiem [Polish], Brest-Litovsk [Russian]), I have provided alternate spellings in parentheses. When referring to Jewish natives of a particular place, I use the Yiddish form (Timkovitser for people from Timkovichi). When place names appear in the names of organizations, they remain, of course, in the form used originally. To the extent possible, I have used organizational names as they appear in English in Di idishe landsmanshaften fun Nyu York, The Jewish Communal Register , or From Alexandrovsk to Zyrardow: A Guide to YIVOs Landsmanshaftn Archive . When English names are not available, I transliterate directly from the Yiddish.

A friend loveth at all times, and a brother is born for adversity.

PROVERBS 17:17

(Quoted during a debate on mutual aid at the Satanover Benevolent Society,

New York, October 1, 1905.)

Introduction

Landsmanshaftn , associations of immigrants from the same hometown, became the most popular form of organization among Eastern European Jewish immigrants to the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The principle of landsmanshaft (if not the term itself) has had a long presence in Jewish history. As early as 586 BCE , Jews in the Babylonian Exile formed separate congregations based on the towns in Palestine from which the worshipers had come. In sixteenth-century Thessaloniki (Salonika), Greece, Sephardic Jews maintained at least ten synagogues identified with their regions of origin in Spain, Portugal, and Italy.

Despite the ubiquity of landsmanshaftn, New York remained their most important center of activity in the modern era. With over 1.5 million Jewish inhabitants by 1920, the city had become the greatest Jewish population center of all time.

The landsmanshaft principle was in no way peculiar to Jewish migrants. In fact, it is one of the most common forms of immigrant organization throughout the world, and groups as diverse as Chinese in Singapore and Ibo in Calabar, Nigeria, have formed associations based on village or region of origin.

Despite their many similarities, however, cultural and social differences leave their marks on the structures and activities of hometown associations of different groups and different times. For example, while Jewish landsmanshaftn were generally loose enough to allow membership to immigrants from other towns (often spouses or in-laws of landslayt ), early Arab-American hometown societies were sometimes so exclusive that marriage to an outsider could mean expulsion from the association. Hometown clubs of immigrants from the Dominican Republic in the 1990s frequently sported baseball or softball teams, an activity common to both their native and adopted countries, while early-twentieth century Jewish societies never concerned themselves with athletics.

The ways in which immigrants and their descendants forge new ethnic American identities constitute a central concern of immigration history. One issue revolves around the degree to which immigrants retain elements of their cultures of origin. Scholars have long since abandoned the notion that the act of resettlement, by removing migrants from their old-country cultural contexts, leaves them empty of any strong attachments and therefore ready on arrival to receive the imprint of their new country. But neither do immigrants transplant their old-country cultures intact to the New World.

In addition to accepting both continuity and transformation as features of the immigrant experience, this approach thus recognizes that ethnic identity is a socially constructed and malleable phenomenon. Moreover, individuals and groups play an active role in the creation of their own identities. Ethnicity, in this view, thus consists of a dynamic process of construction or invention which incorporates, adapts, and amplifies preexisting communal solidarities, cultural attributes, and historical memories. An exploration of this process of construction raises more specific questions about what the immigrants themselves have meant by Americanization. What have they wished to retain from their old-world cultures and historical memories? What aspects of this countrys culture have they most wanted to incorporate into their own? How have preexisting communal solidarities contributed to the process of Americanization? How have all of these attributes been incorporated into a new sense of American identity, and what are the venues in which this new identity has taken shape?