Copyright 2019 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-8122-5136-4

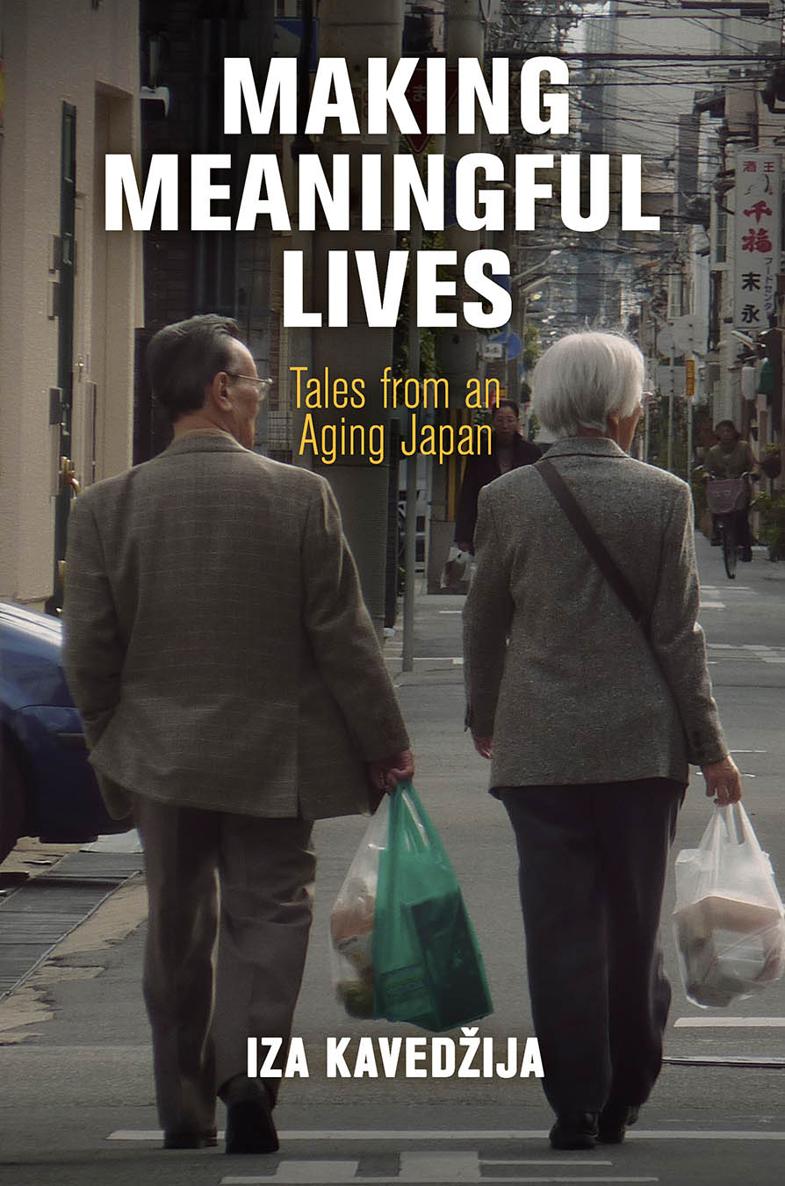

Must an anthropology of the elderly be about aging? There are many things we can hope to learn from a study of older people, and in particular we might expect to find out more about aging itself and how it is experienced; aging is, after all, a process that affects us all deeply. Paying close attention to the changes it entails often seems to lead to a consideration of the challenges that ariseincluding, especially, issues of loss and decline. To be sure, for some, these can be important or even defining facets of life in older age. For the Japanese men and women who are the focus of this book, however, the experience of aging was not a primary concern. Anthropologists tend naturally to be interested in what the people with whom we work care most about; and while my interlocutors did occasionally speak about aging, at times in a reflexive way, they simply did not define themselves in terms of their old age, or allow it to overshadow how they thought of themselves or their companions. Life in older age is not all about senescence, as they reminded me constantly through their actions and attitudes.

Approaching the end of life does, however, often seem to bring to the fore certain existential questions concerning life, death, and connection to others. In this sense, we might think of an anthropology with the elderly as, among other things, a kind of existential anthropology, exploring life lived and experienced: life as it is thought, but also as it unfolds in practice. As such, it deals explicitly with questions of how people see their liveswhether as a whole or in fragmentsin relation to the world that surrounds them, and the role of stories in framing and shaping a life and crafting the wider sociality in which it is imbricated. In leading a meaningful life, what is it that people most care about, and how do they compare their cares of today to those of yesteryear? How do people deal with existential issues, and how do they come to an understanding of what makes life worth living?

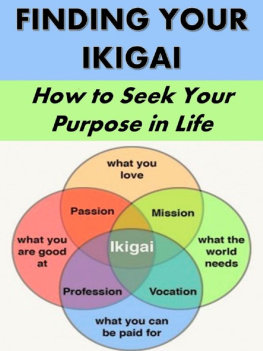

A Purpose in Life: Ikigai

A central concern of this book is the complex relationship between the good life, or what it means to live well, and ones sense of meaning or purpose in life. In the Japanese context, a useful starting point for exploring this issue is the concept of ikigai. This can be translated as that which makes ones life worth living, or what makes life livable, as it were. One might or might not have an ikigaiin which case the term refers to a particular motivation to live or a purpose in life. In the past, ikigai was related to the social value of a persons life, but since the nineteenth century the usage has changed somewhat and now incorporates a sense of happiness in life (Wada 2000). Despite this gradual shift in meaning, however, the earlier idea of social significance or sense of contribution to the larger social whole appears to have been preserved (Koyano 2009). A line from the well-known text Ikigai ni tsuite (About ikigai) captures this sentiment nicely: People feel [that they have] ikigai mostly when they think that their own wishes and duties (to others) are in agreement (Kamiya 1966, cited in Koyano 2009:23). The genealogy of the term helps to highlight the intrinsic link between happiness, meaning in life, and the fulfillment of a social role.

Interestingly, however, ikigai is widely seen by Japanese as problematic, or as an especially pertinent issue for certain social groups. The elderly, in particular, are seen as vulnerable in this regard.

If the ikigai of the elderly is seen as particularly problematic and older people are seen as vulnerable to its loss, this opens an existential question that is both personal and social. If ones role as a mother or a valued employee provides one with an ikigai in the form of a child or work, ikigai becomes an issue when ones role is unclear. Longer life expectancy means that people spend more time in what Ernest Burgess (1960) referred to as the roleless role. Ikigai thus becomes a social issue, a matter of concern, when it no longer naturally unfolds from the social role itself. While this does not mean that the elderly have no social role to perform, it is likely that this role is changing due to economic and demographic circumstances. These new circumstances mean that there are fewer models for a meaningful older age, fewer cultural scripts that provide a sense of older peoples position in the society. The older people in Shimoichi and elsewhere, by drawing on a range of available scripts and crafting their own stories of life well lived, are at the forefront of a social change. If social change is sometimes seen as a domain of the young, the case of my older friends shows that the elderly can change that story too. One story that they were actively rewriting is that of the elderly as a burden and those who need care.

For many of my interlocutors in Shimoichi, care emerges as a central concern: care not only as a form of embodied work in support of older people, but also as an attitude, or a form of attention to others underlying social relationships between the inhabitants of Shimoichiamong neighbors and friends, and not restricted to the family or professional carers. In this broader sense, care indexes what matters, not in the form of static or clearly delineated, abstract values alone, but through practice.

What and who one cares for is then closely related to purpose in life, sometimes considered the basis of ikigai. In this sense, ikigai can refer to a more general form of well-being and pleasure in life, especially when used in relation to the elderly. This raises certain existential questions in relation to older age: does maintaining a particular purpose in life, a well-defined source of meaning, remain possible or even necessary in older age? Indeed, do even younger people have or need such a well-defined purpose? To what extent are life stories relating to meaning and purpose in ones life related to stories of expectations and values in the broader society? In short, I argue that the issues of aging and the good and meaningful life are inextricably connected.